Next weekend is spookier than most at BFI Southbank – which is saying something, since the BFI Gothic season rolled into town. The Hauntology weekend takes over, with a screening of the majorly creepy drama-documentary Häxan on Friday 13 December, and on Saturday night, a collection of gothic treasures soundtracked by a group of seriously talented musicians – Sarah Angliss and the Spacedog ensemble. Here’s a little more about what you can expect from the shows – scroll down for a chance to win tickets to see Häxan.

The ensemble was put together by Sarah Angliss, a composer, automatist and theremin player, whose singularly unsettling music was recently heard at the National Theatre as a tense underscore to Lucy Prebble’s The Effect. Angliss’ music for Gothic film will be performed by her band: recent Ghost Box guests Spacedog. They’ll be joined by Exotic Pylon’s Time Attendant (Paul Snowdon) who will be supplying a new work on simmering, tabletop electronics. There will also be some extemporisations from Bela Emerson, a soloist who works with cello and electronics. Fellow Ghost Box associate Jon Brooks, composer of the haunting Music for Thomas Carnacki (2011), will also be creating a studio piece for the event.

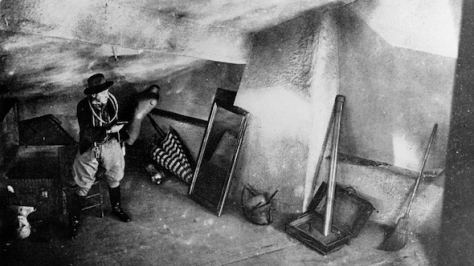

Sourced by Bryony Dixon, the BFI’s curator of silent film, many of the short films inspiring these musicians were made in the opening years of the twentieth century. The Legende du fantôme (1908) and early split screen experiment Skulls Take Over (1901) are on the bill, along with the silent cubist masterpiece The Fall of the House of Usher (US version, 1928) and more.

“There is undoubtedly something uncanny about the earliest of these films”, said Angliss. “Many are stencil-coloured in vibrant hues, adding to that sense of the familiar taking on a strange cast. They seem to demand music that suggests rather than points up the horror, a motif that discomforts as it soothes, or a sweet sound that is somehow sickly, as though heard in a fever.”

Brooks added “the visuals suggest aural textures reminiscent of painted glass, to strange derivatives of stringed instruments. Hopefully I’ve conjured some playfulness amongst the macabre too.”

Adding to the strangeness are Angliss’ automata, who will also be performing live. These include a polyphonic, robotic carillon (bell playing machine) and Hugo, the roboticised head of a ventriloquist’s dummy who is of the same vintage as some of the films. The event will be directed by Emma Kilbey. After the BFI Southbank performance there are plans to take Vault to Gothic revivalist buildings around the UK.

Sarah Angliss is grateful to PRS for Music for financially supporting her new work. Vault: Music for Silent Gothic Treasures is part of the BFI’s Hauntology Weekend, in association with The Wire magazine (Fri 13 Dec – Sat 14 Dec)

To book tickets for Vault: Music for Silent Gothic Treasures, click here http://bit.ly/bfivault. The screening takes places a 8:45pm NTF1, BFI Southbank, Saturday 14 December.

On the Friday night, the Häxan screening will also be accompanied by live music: a specially commissioned score from Demdike Stare.

This 1922 documentary-horror masterpiece explores the effect of superstition on the collective medieval consciousness. Presented for the first time with a BFI-commissioned score by electronic artists Demdike Stare. The duo base their music on samples from old recordings, twisted into new sonic shapes. The blend of Demdike Stare’s resurrected aural phantoms and Christensen’s Satanic horror promises to be a singularly modern yet arcane live experience.

Häxan is a thrilling movie, and an amazing thing to experience on the big screen – an effect that will surely only be enhanced by those “aural phantoms”.

To book tickets for Häxan with Demdike Stare, in association with Wire Magazine, click here. The screening takes place at 7pm in NTF1, BFI Southbank, Friday 13 December. Tickets cost £15 full price – concessions are available.

Win! Win! Win!

To win a pair of tickets to Häxan with Demdike Stare, email the correct answer to this question to silentlondontickets@gmail.com with “Haxan” in the subject line by noon on Wednesday 11 December 2013.

- Which American writer provided the voiceover for Häxan’s jazzy 1968 re-release?

The winner will be chosen at random and notified by email. Good luck!