This weekend, something momentous is happing in California. Kevin Brownlow’s mammoth restoration of Abel Gance’s legendary epic film Napoléon is screening at the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, accompanied by the Oakland East Bay Symphony Orchestra playing the US premiere of Carl Davis’s wonderful score. Wow. That’s five-and-a-half hours of majestic, groundbreaking silent cinema with fantastic live music, and it’s not an opportunity that comes along very often. If you want to be there, you need to know that there will be two screenings this weekend, and two the next: tickets are available here, starting from around $50 and going up to $550 for a premium seat including a gourmet dinner and reception with Brownlow and Davis.

Unfortunately, it’s not a cheap proposition for us Silent Londoners if you throw in the cost of flights, hotels and taking leave from work. While a few friends of the blog are making the trip west for Napoléon, most of us will be sitting at home, trying not to let the jealousy get the better of us.

But there’s no need to succumb to the green-eyed monster. Napoléon last played in London in 2004 and although Brownlow is adding new footage all the time (the original film ran at around nine hours) so the California screenings will technically be an advance on those shows, it’s only a matter of time before Gance’s masterpiece makes its way back to us. What I’m hearing, from reputable sources, is November 2013, at the Royal Festival Hall.

However, if that still seems like a long way away, and you’re suffering from FOMO (otherwise known as the Fear Of Missing Out), here is a five-point guide to help you pass the time, and overcome the Napoléon blues.

1 Get your Photoplay fix

Napoléon isn’t the only film to have been restored by Brownlow and Co, nor is it the only one to benefit from a Carl Davis score. Tickets are already available for Ben Hur at the Royal Festival Hall this summer. And if you want to look even further ahead, the Philarmonia Orchestra will accompany The Thief of Baghdad at the same venue in June 2013.

2 Do your homework

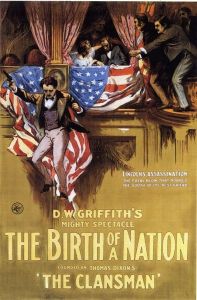

The story of how Abel Gance struggled to make his masterpiece, how it was shredded and how Kevin Brownlow pieced Napoléon back together starting with the 9.5mm snippets he bought as a schoolboy is worthy of a film adaptation itself. You can read all about it in Brownlow’s book, which is available to buy here with a sampler CD of Davis’s score. Napoléon has been all over the American media recently too, in the runup to the Oakland shows, so there’s plenty more to devour. You can read Martin Scorsese in Vanity Fair, or this neat MUBI post, which tells the story of the film via its many posters. The Wall Street Journal and New York Times both printed heavyweight features about the film, Gance and Brownlow’s restoration. If your French is up to the task, the San Francisco Silent Film Festival blog has posted some original articles from the French press about the making of the movie. I also enjoyed this Smithsonian blog that pushes The Artist to one side to say that this restoration is the silent film event of the year. And who can argue with that?

3 See the bigger picture

Of Gance’s many extraordinary technical and artisitic innovations in Napoléon, the most famous must surely be the film’s climactic triptychs: a way of creating an early form of widescreen that required three cameras on set and three projectors in the cinema. This Polyvision effect is also one of the reasons why the film is so rarely shown. Intrigued? On 29 April, more or less fresh from the Oakland screenings, Kevin Brownlow is speaking at the Widescreen Weekend festival in Bradford, and it’s a fair bet that he will mention Napoléon. The subject of his lecture is: ‘From Biograph to Fox Grandeur. Early Experiments in Large Format Presentations’. It strikes me that if you want to learn more about Polyvision from the man who knows more than most, that’s the place to be. If you’re lucky, he may even screen a clip or two.

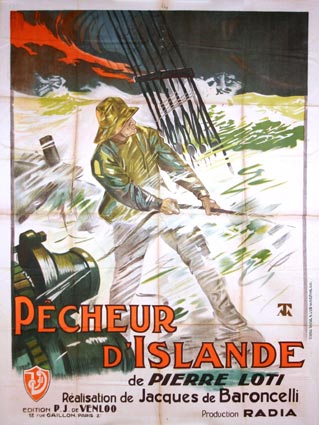

4 Gen up on Gance

Of course, Napoléon wasn’t Gance’s only film. It wasn’t even his only great film. If you have the technology to play Region 1 discs, Gance’s anti-war film J’Accuse (1919) and his impressionistic railway melodrama La Roue (1923) are both available on very nice DVDs, courtesy of Flicker Alley. At around four-and-a-half hours long each, they are ambitious by any standard, although they can only hint at the scope of Napoléon, and they’re well worth devoting a clear afternoon and a coffee pot to. If you’re shopping around for import DVDs, you may well find the four-hour cut of Napoléon, with Carmine Coppola’s score. It’s not quite the real deal, of course, but still fascinating.

5 Clear out your attics

Brownlow’s restoration of Napoléon is magnificent, but it’s still not complete. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if there was more waiting to be discovered? And unearthing the final reels of a film this important is surely every silent cinema geek’s number one fantasy. Apart from the ones that involve a close encounter with Buster Keaton/Louise Brooks (delete as applicable), that is.