In the silent era, films were far more ephemeral than they are today. The fragile nitrate was unspooled for a few shows in each cinema that rented them, and then sent away, re-used, melted, left to crumble and decay or burst, suddenly, into flames. It was a time before retrospectives and archives and museums of the moving image. Now we see films in very different way. In the digital world, although the films seem to have lost their physical presence, becoming data streamed or downloaded on to screens of all sizes, they have the illusion of permanence. Central to this is the arthouse home video market, which packages films like books, as objects to be cherished, or maybe hoarded. A shelf full of gleaming Criterion Blu-rays is as imposing as a line of leather-bound novels – talismans of high culture and prized possessions. We don’t just watch films now, we expect to own them: explore them rewind and freeze and read around them.

Marcel L’Herbier’s Art Deco science-fiction drama L’Inhumaine is as much an art object as a film, and as such, it is the perfect Blu-ray movie. This glittering feature was designed to be admired from all angeles, its intricate and self-consciously beautiful design is the 1920s equivalent of 4K high-definition. I dare you to watch it without your finger itching for the pause button.

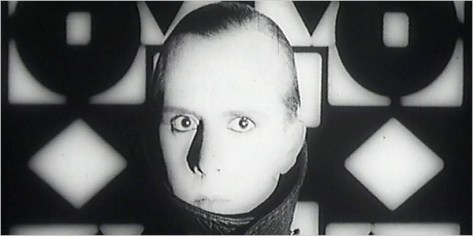

The inhuman woman of the title is a lady who knows a thing or two about being admired from all angles. Claire (played by soprano Georgette Leblanc) is an opera singer who lives in a stunning modernist home, which she opens to a select group of guests, a fawning salon of important men who jostle for her attentions. Everything about Claire’s world is both chilly and extravagant. The dinners she hosts are served at a dining table surrounded by an indoor moat. A drift of swans putter around the guest, more of Claire’s captives, but the only ones present who are indifferent to her beauty. When Claire hears that one of her admirers, Einar (Jaque Catelain) has killed himself after she rejected him, she experiences a slow awakening of her passions, and a more literal resurrection of her body, via a poisonous snake and an electric re-animation machine.

As Claire is beautiful but cold, so is the film. There’s little sentiment in this story, but there is great style. Even the intertitles glitter. L’Herbier conceived the film as a “miscellany of modern art” and he collaborated with artists and designers to ensure that L’Inhumaine was a showcase of contemporary decorative styles. Paul Poiret, René Lalique, Fernand Léger, Robert Mallet-Stevens, Alberto Cavalcanti and Claude Autant-Lara were among the talents brought in to make L’Inhumaine the jewel that it is. Bold tints and rapid edits combine to create a very cerebral kind of impressionist film-making.

There is also something ever so slightly odd about L’Inhumaine and it is never far from absurdity. Those swans in the fining room, say, or the gleaming laboratory designed by Léger. The sequence when Einar broadcasts Claire’s voice to the world via radio, and shows her the faces of people listening to her broadcast around the world on a screen is frankly bizarre, but you can’t fault it for ambition.

L’Inhumaine is liable to leave you unmoved but agog. It’s a gorgeous artefact, though, and a film that reveals L’Herbier’s tendency to high style taken to extremes. If you want to revel in this fantasy of aesthetic perfection, then the new Blu-ray release from Flicker Alley is just the ticket. The new restoration by Lobster Films reveals every inch of those highly wrought designs, and gives the tints the punch they deserve. There are two soundtracks: one by the Alloy Orchestra and another slightly more experimental one by percussionist Aidje Tafial. I enjoyed both – really this film must be a dream to score, with so many tones and textures to play with.

In an ideal world, one designed by the finest artists, I’d have enjoyed a commentary track – this is the kind of film that would benefit from an expert guide. Still, there is an interesting French-language doc about the making of the film, and another on Tafial’s music. Illustrated booklet essays also provide insight and introduction to the film and L’Herbier himself.

Critics were divided, violently, on L’Inhumaine when it was released. Many hated it, but there were those who saw its importance to the medium. Architect Adolf Loos called it “a brilliant song on the greatness of modern technique” seeing correctly that this film is a declaration of intent. L’Inhumaine is a manifesto for modernity and call for film to be considered as art. It’s a lesson that we think we have learned, now that movies endure longer than a flickering entertainment at the matinee, that we save them and store them and even blog about them. But ours is also an era when franchise blockbusters can be illegally downloaded on to mobile phones. L’Inhumaine is the sort of film that commands a little more respect – and attention. Without films like this, cinema would be lost.