This review is an extended version of the programme notes I wrote for a screening of The Treasure (Der Schatz, 1923) at the 2018 Hippodrome Silent Film Festival.

– contains spoilers –

Austrian director Georg Wilhelm Pabst made great films in the early 20th century. However, by the time that he died in 1967, his reputation was all but demolished – his decision to work in the German film industry during the second world war having overshadowed his earlier achievements. Underrated for decades, Pabst’s work is ripe for a reappraisal and his sophisticated and progressive silent films in particular deserve to be more widely seen.

His first film, Der Schatz (The Treasure, 1923), is a Gothic fable in the German Expressionist mode. As such, it initially seems to be out of step with Pabst’s better-known silents, including the gritty drama The Joyless Street (1925), or the iconic Pandora’s Box (1929), starring Louise Brooks, which belong to a different movement altogether: the harsh realism of Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity. In this early work there are nevertheless glimmers of Pabst’s later style, his political values and his psychological insights as well as his sympathy for his female characters and their right to assert their independence.

Pabst was born to Austrian parents in what is now part of the Czech Republic in 1885, and moved to Vienna when he was a child. He studied engineering but by the time he was 20, he realised that the theatre was his passion and he enrolled in drama school. He worked as an actor across Europe and in New York, where the poverty he witnessed, and his contact with the trade union movement, forged his socialist beliefs. Deciding to concentrate on directing, he returned to Europe in 1914 to recruit actors, but on landing in France he was arrested as an enemy alien and taken to a prisoner-of-war camp for the next four years. After the war he directed many plays, especially Expressionist dramas, before, in 1920, going to work with Carl Froelich in the German film industry. In 1922, aged 37, Pabst directed Der Schatz, his first film.

Der Schatz had been adapted by Pabst and his co-writer Willy Henning from a short story by Nobel-prize-nominated author Rudolph Hans Bartsch, published in collection called Bittersweet Love Stories in 1910. A bell-founder called Balthasar (Golem star Albert Steinrück), his wife (the brilliant Ilka Grüning, with salt-and-pepper streak and a bell-shaped dirndl skirt) and daughter Beate (Lucie Mannheim, who later made several films in Britain during the war) and an apprentice called Svetelenz (Expressionist film and stage star Werner Krauss) live in a strange house in a sinister landscape.

Balthasar’s wife has a miserly secret, Svetelenz is dopily but rather charmlessly in love with Beate and shares bell-maker’s brooding obsession with the building’s past. Centuries before, the house had been burned down by Turkish invaders and rebuilt from the foundations; the family believe that the Turks left behind some treasure on the site, but they don’t know where. When a young, handsome and vigorous goldsmith, Arno (an early role for Hans Brausewetter, who had an illustrious career ahead of him in Germany) arrives to work with the bell-founder, he falls in love with Beate, and has his own ideas about how to find the treasure. The collective lust for the gold, and Svetelenz’s jealousy over Beate, risk tearing the group and even the house apart. Suitably for such a high-key Expressionist narrative, the performances are all exaggerated but no loess compelling for that. You can see here the first of Werner Krauss’s five collaborations with Pabst – he played a variety of monstrous figures for the director, from Svetelenz to the title character in 1943’s Paracelsus.

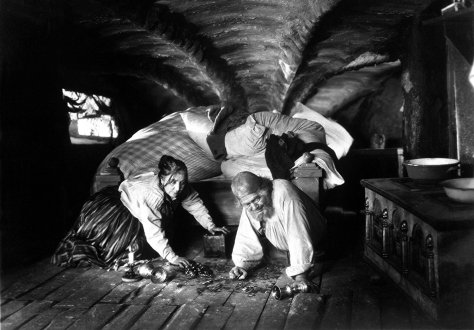

Critic Lotte Eisner praised the film’s grotesque, shadowy design: “Pabst used all the Expressionist paraphernalia,” she wrote. “Here and there in the darkness we perceive a narrow window dimly lighting fragments of a human figure or a gloomy chamber.” Pabst’s son Michael recounted how acclaimed designers Walter Rohrig and Robert Herlth created this exaggerated, unsettling look: “Everything was artificial and built in the studio: the house, the garden, the vineyard, even the butterflies that fluttered around the romantic couple were made out of paper.” The house’s architecture is full of twists, corners and stairs, and low ceilings that force the characters to crouch, bowed at the waist as they stagger and stumble. The men of the house are searching for the gold, via science or superstition, led by diagrams or dowsing rod. While the matriarch has a stash of gold coins she is terrified they will find. This may be “running away” money, but most likely she is just as in thrall to mammon as the men. In her fidgety panic she hides the coins again and again, in her flour jar, her mattress, her blouse, her slipper.

Michael Pabst also claimed that his father’s famously fluid camerawork is in evidence here, but nothing can been seen in the surviving prints. Suitably for an Expressionist work, the film dwells on the darker side of human nature – greed, covetousness and obsession. Pabst was fascinated by aberrant psychology, featuring mad or maniacal characters in many of his films, most particularly the overtly Freudian Secrets of a Soul about a man tormented by a knife mania. There is also a shocking moment when the bell-founder appears willing to exchange his daughter for gold. However, Pabst and Hennings rewrote the ending of the story, giving Beate an opportunity to demonstrate her resistance and Arno a choice between love and money. Thereby, Pabst’s adaptation negates the source story’s original, misogynist conclusion: women and gold attract each other.

That twist, and the film’s frankness about sex (Arno seduces a bar maid en route to the treasure house, and he and Beate share a private moment in a vineyard) are typical of Pabst’s work. While this film doesn’t contain the fluid editing style that Pabst’s later silents were noted for, it has plenty of visual panache, some intense performances and a carefully sustained atmosphere of mounting hysteria. Two spectacular sequences, a flashback to the Turkish raid, and the calamitous finale, reflect the growing ambition of the German film industry in the 1920s.

Pabst’s next film was to be Countess Donelli, starring Henny Porten, which is now lost. The next film he made after that was The Joyless Street, which seems to be a huge advance on the mannered gothic of The Treasure, but a careful excavation of this early work reveals the potential for Pabst’s later greatness, buried just below the surface.

The Treasure screened at the Hippodrome Silent Film Festival in Bo’ness, Sctoland, on 24 March 2018, with the debut of a new score by Aloïs Kott. At the same festival I gave a talk called ‘Lost Girls and Goddesses: Women in the Films of GW Pabst’, which I hope to convert into a new format and share on this site or elsewhere soon.

- Silent London will always be free to all readers. If you enjoy checking in with the site, including reports from silent film festivals, features and reviews, please consider shouting me a coffee on my Ko-Fi page.

any significant similarities or differences worth noting regarding von Stroheim’s “Greed” (1925)?

Interesting question. Two Viennese directors, born in the same year, both working on such thematically similar films at around the same time! The Treasure was released in Germany just about a month before Von Stroheim started shooting Greed, but wasn’t released in the US until 1929 I think. So it’s fairly certain that he didn’t see it before he made Greed. Anyway, both films use elements of Expressionism, and both focus on the way that money, can cause rifts in families and married couples. Both patently depict money-lust as a mental illness, causing irrational and inhumane behaviour, and in particular with the wives (Ilka Gruning and Zasu Pitts) displaying similar obsessive-compulsive habits, touching, counting and hiding the cash. Impossible not to think of Greed when watching this, although the American film feels far more expansive and modern than this dark, grimy fable, set in some obscure time period but probably the 19th century. It’s actually remarkable that there is such a similarity of tone, with Greed being shot so much on location and mimicking the realism and breadth of a novel and this being studio-bound and based on a short story. A great double-bill!