This post, in honour of Women’s History Month, is adapted from a talk I gave at the BFI Southbank recently as part of an event called Broad Strokes: Trailblazing Comedy Screenwriters. You can read a report from that event here.

Anita Loos’s family pronounced their name Lohse, but as an adult she got tired of correcting people and opted for something a little more “Loose”. It suited this true original to reinvent her own name, especially as even that sounded like a good joke. Loos was one of the greatest wits of the 20th century, who wrote one of the best modern American novels, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes – but her career kept coming back to the cinema. It’s where she started. She wrote movies – in several different ways – and she wrote some of the best books about Hollywood too. She helped the cinema grow up and she exposed many of the industry’s foibles as well. Her jokes travelled so far that even if you don’t think you know her work, you may well have been laughing at her best gags for years.

A seriously petite brunette, Loos was born in Mount Shastam California in, whisper it, 1888. She didn’t like that fact to get around and so she lied ferociously about her age, with the vanity of a movie star. Unfortunately for her, films have dates on, so to make the timeline fit, Loos claimed to have been in her early teens when she started writing movies, and thus in her own twenties during the Jazz Age. No. She was more like 24 when she started out, and while she remains one of the greatest chroniclers of the Roaring Twenties, she herself was in her 30s and 40s at the time. That’s a grand age for a wit, actually: old enough to make fun of the naivety of youth, and young enough to be aghast at the staidness of the older generation.

Loos had four main topics: sex, fashion, gossip and men. She wrote about what interested her. She was a fashion plate, a storyteller and she loved men, even though they consistently disappointed her. She was briefly married in her youth, which was a juvenile mistake – he was skint and boring – and simply her ruse to leave home. In 1919, however, she married writer-director John Emerson and she stayed married to him until he died in 1956. She was besotted with him at first, but he soon let her down, reinforcing her opinion that sex was some sort of absurd cosmic joke played on unsuspecting mortals.

They worked together, which is to say, as she recalled it, she worked while he lay in bed watching her. “I had set my sights on a man of brains, to whom I could look up,” she later said, “but what a terrible let down it would be to find out that I was smarter than he was.” He was a philanderer, a malingerer and took most of the credit and at least half the money for their collaborations. Sam Goldwyn said “Emerson was one of those guys that lived by the sweat of his frau” and Loos’s friend Charles Lederer called him “Sweet Mister E of Life”. One time, it seems, he tried to strangle her. But he did not write Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, so we won’t mention him again unless we absolutely have to.

As a young girl, Loos wanted to be a writer. And she loved the movies. So she found the address for the Biograph studio in New York and she began sending in story ideas. These were more like what we’d call scenarios, and she wrote around 200 of them, for around $25 apiece, before she ever entered a movie studio.

The first of Anita Loos’s career highlights is The New York Hat, a single-reel drama from 1912: a comic-serious collision of sex, fashion and gossip, and the first of her scenarios to be produced. It’s also one of my favourite movies of all time. Loos’s scenario was developed for the screen by another great silent screenwriter, Frances Marion, and directed by DW Griffith.

In the film, Mary Pickford’s mother gives the local vicar some money on her deathbed because she knows her husband won’t provide the accoutrements a young woman needs as she grows up. Sure enough, young Mary soon needs a new hat, and the clueless vicar (Lionel Barrymore, making his debut) buys her the most extravagant model in the small town boutique – a $10-dollar monstrosity from New York. When Mary wears her grand new hat to church the town is in an uproar. They know who bought the hat and assume such a lavish purchase can only mean an illicit affair is in progress. Thus we introduce another of Loos’s key themes – men being clueless. The New York Hat is played almost straight, a moving drama with a happy ending, but it’s also very funny. The reaction to Mary’s ludicrous hat when she wears it to church is great cringe comedy.

Griffith vastly admired Loos’s scenarios, and produced scores of them. He even brought her to Hollywood and put her on the payroll, but the full-fledged scripts she wrote him there were never produced. Griffith said they were unfilmable because “the laughs were all in the lines, there was no way to get them onto the screen”. However, in 1916, when he was making his followup to Birth of a Nation, he made a very wise decision. He hired Loos to write intertitles for Intolerance. This is a very serious epic film, intertwining four different stories from four different time periods and getting on for four hours long. Some of it’s great, but – well let’s just say, the injection of Loos’s pithy wit is very welcome.

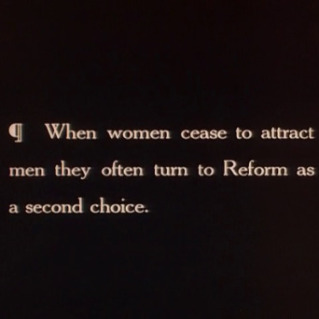

This is one of her most celebrated titles from Intolerance. Mean it may be, but it’s very funny. Elsewhere, she compares an ancient slave auction to the modern marriage market and describes middle-class people who donate to charity as “meddlers”. Griffith called her “The world’s most brilliant woman” and Intolerance would be much less enjoyable to watch without her input.

The finest intertitles are exercises in concision: conveying narrative and character information in the fewest words possible. One of the best ways to do that is with a joke, and Loos was a master of the form. As Griffith said: “The most important service that Anita Loos has so far rendered the screen is the elevation of the subcaption [sic], first to sanity then to dignity and brilliance combined.”

Loos first unleashed her comic talent with a very funny man – and one of the biggest stars in early Hollywood: Douglas Fairbanks Sr. His first star vehicles were loopy, often surreal comedies, laced with druggy hallucinations and making fun of modern fads from horoscopes to vegetarianism. In The Mystery of the Leaping Fish (1916) Fairbanks stars as a drugged detective, Coke Ennyday, trying to crack a case, and in His Picture in the Papers (1916), Fairbanks is a rich young man trying to prove his importance to his father by becoming famous.

Loos’s scripts helped to make Fairbanks a star, but her contribution did not go unnoticed. The New York Times praised the wit of her title cards, saying “satire has invaded the screen; the movies are growing out of their infancy”. Loos was getting as much publicity as the star, and Photoplay called her “the Soubrette of satire”. More to the point, Famous Players Lasky offered her a contract, this time in her beloved New York.

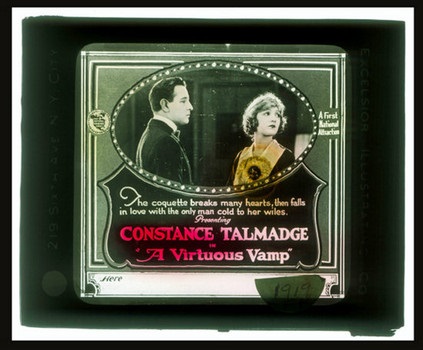

Loos’s next star collaboration was with an actress who was vastly popular in her day, but sadly not so well-known now: Constance Talmadge. Loos liked Constance very much, and enjoyed her “humour and her irresponsible way of life”. As well as writing several comic films for her friend, she later wrote a family biography of Constance and her sisters, called The Talmadge Girls. While Loos would often embroider the details of her own life, books such as this carry considerable historical value. She became very protective of the female stars she worked with – she saw and understood the pressures they were under. As well as giving them great scripts to work with, she wanted to represent them well, and tell their side of the story, rather than the story that executives and publicity men wanted to tell. Loos is one of the most powerful voices in what we might call the feminist counter-history of Hollywood. Karina Longworth’s new book, Seduction: Sex, Lies, and Stardom in Howard Hughes’s Hollywood, which makes the radical choice to tell the playboy’s story by telling the stories of the women he knew instead, is the latterday continuation of this process.

Loos’s jokes about men and woman and sex are part of our feminist weaponry now. But she was not a feminist, not as she understood the term. She railed against the women’s libbers later in life – implying that they wouldn’t be so grim-faced if they had more sex, or laughing off their cause by saying “They keep getting up on soapboxes and proclaiming that women are brighter than men. That’s true, but it should be kept very quiet or it ruins the whole racket.” Her views reflect the era she was born into. We could go further: Loos was politically very incorrect in lots of ways. Many of her jokes we’d consider offensive now – and although we might allow that in the matter of race, she reflected the prejudices of her time, not everyone shared her views so I don’t think that makes her above criticism. In one way she actually been flattered by history, as Fairbanks, who was fairly progressive on this front, used to go through her intertitle drafts and edit out any ethnic slurs he found.

The subject of men, women and sex brings us to Loos’s greatest achievement. In 1925, Loos published her masterpiece, first as short stories in Harper’s Weekly and then as a full-length novel. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is a comic tour de force, and no less than Edith Wharton called it “The great American novel”. This breathless and ungrammatical text is presented as the no-holds-barred diary of one Lorelei Lee, a beautiful blonde gold-digger from Little Rock, Arkansas, and her adventures in pursuit of a diamond tiara with her friend Dorothy, a brunette with a one-track mind. As Lorelei puts it: “Fate keeps on happening”.

The great writer H.L. Mencken told Loos he couldn’t print it in his magazine for fear of offending the readers, saying “Do you realize, young woman, that you’re the first American writer ever to poke fun at sex?” Loos wasn’t just poking fun at sex, she was poking fun at men – and specifically H. L. Mencken. Loos vastly admired Mencken, finding him much more scintillating than Emerson, for example, but she was taken aback one time, when she thought they were having a thrilling conversation, to see him turn away and focus his attention on a blonde, with much less to say for herself. That’s what inspired the book. Lorelei may play dumb, but she isn’t really, and the butts of the novel’s jokes are the men who cave in her presence, offering her diamonds and ocean liner tickets at a bat of her eyelashes. Here’s a quote from the book that sums up its technique. For all Lorelei’s comic misunderstanding and misspellings, she is exposing a great untold truth about human relations:

“Dorothy looked at me and looked at me and she really said she thought my brains were a miracle. I mean she said my brains reminded her of a radio because you listen to it for days and days and you get discouradged and just when you are getting ready to smash it, something comes out that is a masterpiece.”

Emerson tried to prevent the publication of this novel, of course – he strongly “discouradged” Loos from doing so. The book’s brilliance, of course, exposed another great untold truth about their working collaboration – that it was not a partnership of equals. He even tried to insert a dedication into the manuscript claiming credit for teaching the author everything she knew – luckily her friends intervened. Undaunted, Loos capitalised on her classic. She wrote both a sequel, But Gentlemen Marry Brunettes, and a stage adaptation.

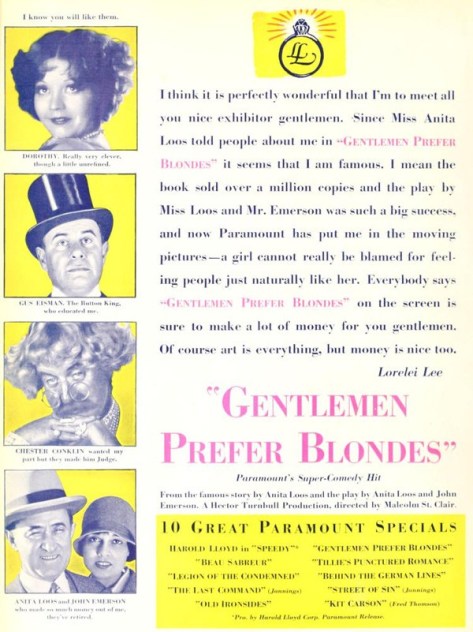

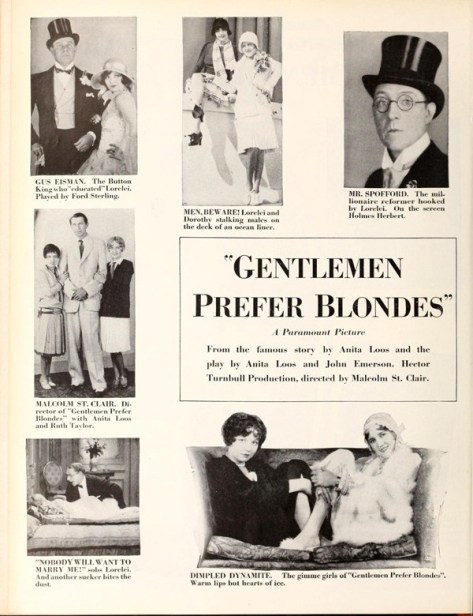

As Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was a hit novel and play, of course it had to be filmed. The film was a hit too, but sadly it is now lost. The 1928 Gentlemen Prefer Blondes had impeccable comic credentials, being directed by Keystone alumnus Mal St Clair, and starring two more former employees of Mack Sennett: Ruth Taylor and Ford Sterling. Alice White picked up the part of sidekick Dorothy after Loos nixed the studio’s original, and intriguing, choice of Louise Brooks. Brooks is said to have given a joyless performance in her screen test (“I stunk”), and Loos dismissed her, saying: “If I ever write a part for a cigar-store Indian, you will get it.”

Taking a look at the promotional material tells us a lot about the film, and Loos’s stature, though.

Reviews of the film were a little muted after all that hype, with Variety saying it lacked the sophistication of the stageplay and that “Miss Loos has ‘adapted down’ and ‘sapped up’ to the film public”. I’d still love to see it.

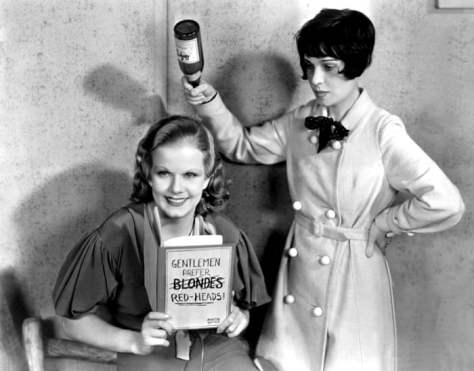

When the talkies came in, Loos was hired by Irving Thalberg to work for MGM. He wanted Emerson too, but he refused to go. Here Loos wrote screenplays as we would understand them now, and all the concision and wit she used in her title cards came out in dialogue that followed the three Rs: rapid, risqué and ribald. Finally she could get the laughs in her lines into the picture. Who better than Loos, for example to write a script for Jean Harlow, the 1930s ultimate Lorelei Lee type, breathless, blonde and babyishly naïve? Except she was adapting a book by Katharine Brush called Red-Headed Woman, which was a cue for plenty of promotional jollity.

Loos had been brought on to write the Red-Headed Woman script after MGM’s first hire, F Scott Fitzgerald, had produced something a touch too serious. Irving Thalberg fumed that “Scott tried to turn the silly book into a tone poem”. What this film needed was humour, so obviously Thalberg turned to Loos, who loved both the book’s lead character Lil film, whom she described as a “sex pirate”. Loos’s humour was vital to the success of Red-Headed Woman. The writing is funny, sure, and packed with double-entendres, but it’s more sophisticated that that: as dry and sharp as a dirty martini. However, at first it was a little too dry. Lil is a mercenary homewrecker and for many people, including those at the preview audience and in the Hays Office, she was entirely unsympathetic. Basically, the film as it stood did not immediately endear Lil to the audience and outraged the censors.

Loos was called back in to add an opening scene that would set the right tone – one of hilarity, which would get the audiences on Lil’s side and appease the Hays Office by showing it was all meant in fun. And she managed to do just that, and get in a plug for her novel too. Harlow is first seen in close-up admiring herself and her new red looks. She addresses the mirror: “So gentlemen prefer blondes, do they?” We next see her in a department store changing room holding out her skirt. She asks her friend if the fabric is transparent, who replies: “I’m afraid so.” Naturally, Harlow grins and says: “I’ll wear it then!” It’s an solution that is as economical, and witty, as Loos’s best intertitles.

Loos didn’t get on very well writing scripts at MGM, as a rule, although Red-Headed Woman was a smash and she was Oscar-nominated for San Francisco (1936). Her last great Hollywood screenplay was The Women, directed by George Cukor in 1939. Other writers had failed to adapt this all-female play, but Loos was right at home. Here’s a snippet of one of the most brilliantly written, and poisonous scenes. It’s a confrontation between Mary, played by Norma Shearer, and Crystal, the woman her husband Stephen is sleeping with, played by Joan Crawford.

The film was a smash-hit, and the secret of its success lies not just in the delicious tension you can sense in this scene but in Loos’s unstoppable skill with a on-liner, whether it’s Crawford purring, “If Stephen doesn’t like anything I’m wearing, I take it off”, or later making her farewell with this lethal kiss-off:

After this, Loos went back to New York, and wrote for the stage – not without success. She wrote the book for a musical adaptation of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, which was a little milder than the novel and starred Carol Channing and Yvonne Adair as Lorelei and Dorothy.

She also adapted Colette’s Gigi into a stage play, giving a young actress called Audrey Hepburn her first big break.

Then, of course, 20th Century-Fox and Howard Hawks came for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. It remains a great joy to see two great comediennes, Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell, both of whom were exploited by Hollywood in their turn (again, read Seduction for the full, sordid story of Russell and Hughes), enacting this superb comic revenge on stupid men. The 1953 film has some great moments, but it’s a little sluggish in between times. Never mind: the song Diamonds are Girl’s Best Friend is the best possible tribute to Loos’s satirical pen, and the staging of Isn’t There Anyone Here for Love? in which Russell cavorts among an entire male Olympic team, must surely have tickled her. But Loos had nothing to do with the production, having struggled with her writing partner on the stage version. She did, however, say that Monroe was sublime casting. And of course, she was 100% right.

Loos never worked for the cinema again, but she continued to write, for magazines mostly. She needed to keep working: she never divorced Emerson, and in fact supported him through long periods of illness. When he first fell seriously ill in 1937, Loos discovered that he had frittered away much of their income and she was fairly broke. So she couldn’t afford to rest on her laurels.

Loos’s writing never flagged. She is the author of two brilliant and quite unreliable memoirs: A Girl Like I and Kiss Hollywood Good-By as well as The Talmadge Girls. She lived out the rest of her days in the most expensive clothes she could afford, going to as many parties as she could and telling stories that could make your hair curl, to her crowds of admirers. “I’ve had my best times when trailing a Mainbocher evening gown across a sawdust floor,” she wrote. “I’ve always loved high style in low company. ” She died on 18 August 1981, and she remained “the world’s most brilliant woman” to the end.

As Lorelei Lee would say: “a girl with brains ought to do something with them besides think”.

- 30-Second Cinema, which I edited for Ivy Press, is also published today. You can order a copy here.

- Silent London will always be free to all readers. If you enjoy checking in with the site, including reports from silent film festivals, features and reviews, please consider shouting me a coffee on my Ko-Fi page

Fascinating. What a career!

loved reading this!

Great. RE-posted on twitter @trefology

Great piece! Anita was a true talent, not least in self-aggrandisement. 😉 The 1928 Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is one of my holy grail lost films.

Ha you’re not wrong. Imagine if we ever got to see that film though? Swoon!

When I was with Anita Loos in 1972 at a lunch in the Book Cadillac Hotel in Downtown Detroit(Summer) she was old, yes, but still as elfin as she looks in the wonderful photos in the above article. I met an old lady selling up her book library in a large house on Outer Drive in Detroit(she was move away) later that year and she reminded me so much of Anita. Good memories.