Sight & Sound’s decennial poll of the Greatest Films of All Time attracted a lot of attention earlier this summer, when the critics toppled Citizen Kane off the number one spot, using Vertigo as a battering ram. Of far more interest to us was the fact that three, yes, three silents made their way into the top 10, with Battleship Potemkin skulking just outside.

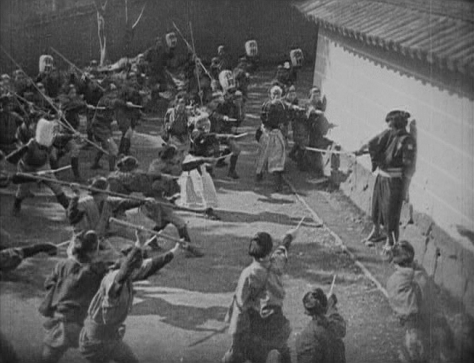

This is great news for silent fans in that airy-fairy way that we like to see our best-loved titles acknowledged – and these three films are undoubtedly classics. They are my favourite, Murnau’s sublime Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, Dreyer’s unforgettably cathartic The Passion of Joan of Arc and Vertov’s exhilarating experiment Man With A Movie Camera. There is a more substantial reason to get excited though: all the films in the Sight & Sound top 10 will be shown at the BFI Southbank in September – and you’ll find these silents already on the calendar.

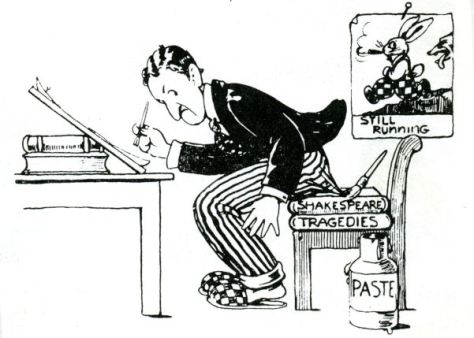

The news gets better. You can win a pair of tickets to any of these screenings and all you have to do is tell me how much you want to go. Complete one of these sentences in 15 words or fewer to win a pair of tickets to the screening of your choice – as well as a pair of tickets to the Call it a Classic? panel discussion at the beginning of the month. I’ll pick the best sentences with an independent judge and our decision will be final. So make your answer as wise, witty or profound as possible!

- I want to see Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans because …

- I want to see Man With a Movie Camera because …

- I want to see The Passion of Joan of Arc because …

Email your answers to silentlondontickets@gmail.com with the name of your chosen film in the subject header by noon on Sunday 2 September 2012. For your information, the Passion and Movie Camera screenings will have live musical accompaniment. The Sunrise screening will have a musical score but not live music.