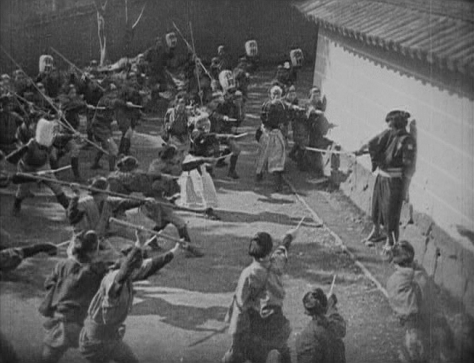

The choices we make in life define us, and this morning I got up bright and early for Viktor Turin’s Provokator (1927), but gave early Selig feature The Ne’er-do-Well (1916) a miss. Did I do right to choose Anna Sten’s anguished student and her revolutionary chums over Kathlyn Williams and the adventures of the rich and beautiful? I don’t know. Provokator, which marks Sten’s cinema debut, was occasionally stirring, but mostly on the pedestrian side, though a raid on the revolutionaries’ den was rather fine, boosted by terrific accompaniment from Gabriel Thibaudeau and Frank Bockius.

Where I may have erred is in choosing such a downbeat opener on a day that was to close with GW Pabst’s heartbreaking social critique Die Freudlose Gasse (1925). However, I am getting ahead of myself. My afternoon was perked up considerably by the patriotic hubbub around Walter Summers’ lovely postwar tearjerker A Couple of Down-and-Outs (1923), introduced by the producer’s grandson Sidney Samuelson, who was seeing the film for the first time. What could be a very harrowing tale is handled with care, as Rex Davis’s Danny finds unlikely allies when he rescues his war horse from a foreign abattoir: manipulative, but charming with it.

The audience groaned in unison at the start of the next screening, as another tranche of German animated shorts kicked off with a toothpaste advert featuring the “tooth devil” cracking open a poor vulnerable gnasher with his drill. It was, as before, a diverting and diverse hour. In the name of commerce, all kinds of unlikely objects have been animated: detergent, rolling pins, matchboxes, kettles and even, in a sweet but fussy stop-motion ad for aspirin, a silent-film star and director (Im Filmatelier, 1927). Günter Buchwald at the piano followed with apparent ease the rapid changes of subject-matter, media and mood – as when a promo film for a department store dwelt proffered a new suit as a suicide-prevention measure (Der Hartnäckige Selbstmörder, 1925).

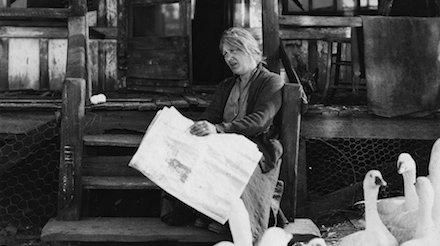

I have a date with Greta Garbo in A Woman of Affairs (1928) on Saturday, but I spent Friday night with both Garbo and Asta Nielsen in the elegant but emotionally gruelling Die Freudlose Gasse (1925), giving a beautiful face to the seedy economic exploitation of women in 1920s Vienna. Both the lead stars are fantastic, and supported by a cast of wonderful character actors including Valeska Gert as a pixie-faced madam. Pabst’s direction veers between sober restraint and wild bouts of inventive, unchained camera excitement. This new print is not quite complete, but mostly crisp, with deep tinting, most especially effective in a fire scene towards the end.

Accidentally profound statement of the day: “The joyless street is long,” exclaimed I, when I read in the catalogue that Die Freudlose Gasse clocks in at 151 minutes long in its present state. It ran for closer to three hours at the Berlin film festival, apparently, but that was based on a projection speed of 16fps, as opposed to the Giornate’s 19fps. Phew.

- For full details of these and all other films in the festival, the Giornate catalogue is available as a PDF by following this link.

- My previous reports from the festival are here.