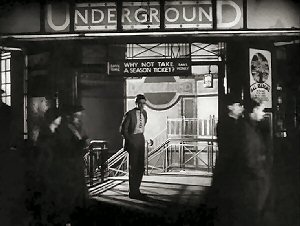

Don’t forget that the BFI’s Genius of Hitchcock retrospective begins in earnest this month. In fact, you can kick off the celebration with a Blackmail silent-and-sound double-bill tonight. For the other silents in the season, check the Silent London Calendar.

First off you won’t want to miss the theatrical release of The Lodger on 10 August – there’s a special screening at BFI Southbank featuring a Q&A with composer Nitin Sawhney too.

Next month, you’ll want to note some other Hitchcock dates in your diary to see the new restorations of his silent films. There’s a second chance to see The Pleasure Garden with Daniel Patrick Cohen’s marvellous score on 13 September. Downhill will screen with a live score from beatboxer Shlomo on 20 September and there’s a screening of Champagne with “boldly classical” music from Mira Calix on 27 September. There’s the restoration premiere of Easy Virtue on 28 September, too.

Plus, it has now been announced that The Manxman will be this year’s London film festival archive gala, screening at the Empire Leicester Square on 19 October with a new score from Stephen Horne. If you saw last year’s gala screening of The First Born, also with a score by Horne, you’ll know this isn’t be missed.

Back to August, the BFI is showing a fine roster of other silent films, including Greed, The Dumb Girl of Portici featuring Anna Pavlova, and Drifters, with a live score from sound artist Jason Singh. Search to find out more on the BFI website.

To win a pair of tickets to the any silent screening at the BFI this month, simply email the answer to this simple question to silentlondontickets@gmail.com with August in the subject header by noon on Friday 3 August 2012.

- What is the name of Hitchcock’s lost silent feature film, starring Nita Naldi?

The Genius of Hitchcock season runs until October and showcases a complete retrospective of his films, from his early British silents, to his later Hollywood classics. Also included in the season is a dedicated microsite, The 39 Steps to Hitchcock, which is a step-by-step guide through one man’s genius, featuring exclusive film extracts, interviews with close collaborators (Kim Novak, Tippi Hedren and more) and a journey through his life and career through galleries curated by Hitchcock experts.