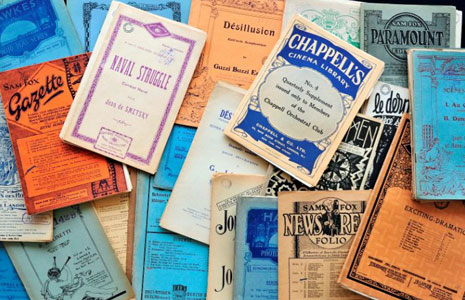

You remember, I’m sure, the exciting haul of silent film music that was discovered in Birmingham last year: the stash contained stock pieces to suit different moods, genres and locations as well as one very specific tune, a Charlie Chaplin theme. There were around 500 manuscripts in total, including compositions for small orchestras as well as solo pianists. The music had been ignored for decades and almost certainly not played in 80 years.

Neil Brand was quoted in the Guardian, explaining the significance of the find:

“This collection gives us our first proper overview of the music of the silent cinema in the UK from 1914 to the coming of sound. Its enormous size not only gives us insights into what the bands sounded like and how they worked with film [but also] the working methods of musical directors. Above all, it gives the lie to the long-cherished belief that silent films were accompanied on solo piano by little old ladies who only knew one tune. When they are played we will hear the authentic sound the audiences of the time would have heard.”

Read more, from the Bioscope, here.

The good news is that this spring, the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra will be playing some of the music as part of a special Charlie Chaplin night on Friday 20 April (they’re screening One AM and City Lights). The even better news is that you can hear some of the music on Soundcloud now. I’m quite fond of Dramatic Love Scene:

And how about The Great Ice Floe?

Or The Smugglers?

You’ll find nine tracks on the Orchestra’s Soundcloud page here. The reason that the tracks have been recorded and uploaded is that the Orchestra is holding a competition, and if you’re a whizz with animation you really should think about entering. The deal is that you have to make an animation to accompany one of the tracks, which includes the word “Birmingham” or an iconic image of the city. The winner will see their work on the big screen at the Charlie Chaplin night in April and receive a placement at the Charactershop animation studio and an Introduction to Final Cut Pro X course.

There are more details on the Orchestra’s website here.