It may seem that the Giornate is in its own bubble, a hundred years or more removed from the real world, wrapped up in the fashions and the fads of the past. But we’re still looking out at the world every day, and no matter how the text on screen tries to guide us, we bring our 21st-century interpretation to everything that passes in front of our eyes. Sometimes the challenge is to wind back the clock, to see the past as our ancestors did when they were living through it. Sometimes we have no choice but to view images of the world as it was while burdened with the knowledge of our shared history, and of our violent present.

Continue reading Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2025: Pordenone Post No 5Tag Archives: Musidora

Silent bulletin: news for September 2024

Back to school time! Here’s a roundup of the silent movie news I really want to share with you as summer turns into autumn. Just think how many of these forthcoming delights you could enjoy for less than the cost of a dynamically priced Oasis ticket.

Screenings and festivals

- I missed StummFilmTage Bonn this year again – both in person and online. But Paul Joyce and Paul Cuff both kept us up to date with their fabulous blogs.

- Wareham Silent Film Weekender. The crown jewel in South West Silents’ autumn lineup is this three-day festival of silent cinema at the gorgeous Rex Cinema in Wareham, Dorset. No lineup news as yet but we know to expect great things from SWS. They are also hosting, for example, a screening of Hitchcock’s The Manxman (1928) in Polperro, close to where it was filmed.

New media nostalgia and the revival of silent cinema style

This is an extended and adapted version of a contribution I made at the 2024 Domitor conference in Vienna. I spoke as part of a roundtable on Curating Early Cinema Today, chaired by Maggie Hennefeld. Full details of the roundtable are at the end of this post.

————-

Media history is doomed to repeat itself, first as travesty, then as art. I’m kidding, but only a little. Here are some thoughts on why early cinema is trending in the 21st century, why I am writing this blog, and perhaps, why you are reading it.

Since the digital transformation of the film industry at the turn of the 21st century brought with it a new surge of creativity and of anxiety, through the rise of audiovisual social media, from YouTube to TikTok and to the dawn of AI, we are living in an age of constant new-media excitement, and panic. These mew forms of communication belong to youth; to older eyes they appear baffling, and probably dangerous. In this state of anxiety and attraction, we have much in common with the spectators of early cinema in the years following the turn of the previous century. Our new platforms, expressly suited for exhibiting the “cinema of attractions”, have created their own stars, and genres. And just like our ancestors sharing in global astonishment at Charlie Chaplin, Asta Nielsen, or Max Linder, we experience anew the enhanced possibilities of mass communication, best expressed by the world-shrinking concept that is “going viral”.

Caroline Golum’s excellent article ‘Cinema Year Zero: Tik Tok and the Grammar of Silent Film’ (Mubi Notebook, 25 February 2021) aligns the fixed-camera, stop-and-start-editing and subject matter of TikTok with the mechanic and style of early cinema. I think her analysis is sharp, and I highly recommend the piece. It strikes me, though, that the best way to describe TikTok, or any new-media platform, from Medium to BlueSky, is to be alert to its specificities as much as to its similarities with other media.

Therefore we should say that while TikTok has much in common with early filmmaking, it is defined by its Chinese ownership, by the portrait-phone aspect-ratio, the placement of screen furniture, the captioning and comments functions, the use of memes and lip-sync comedy, the proliferation of shared music clips and the technique of stitching, an extension of the repost or quote function on other platforms. That it has become a natural home for both infuencers and brand promotion, so has a prominent place in the history of advertising media in particular. We can say that very much unlike early film it is tailored to a single spectator, handheld close to the eyes like a book, not aloft like a projection, and that the scrolling process, with its minimal interaction for maximum content, has more in common with the disaffected channel-hopping of the over-stimulated TV viewer than with cinema exhibition. That the algorithm that fuels the For You Page is similar to social feeds on eg Facebook, but has its own, sometimes, mysterious and ruthless methods[1]. That TikTok is TikTok, and also a collation of concepts from other media. Just as early film has its roots in optical toys, photography and the magic lantern, among other “pre-cinema” objects, and is also its own, glorious invention.

TikTok’s likeness to early film may not persist. Already it is facilitating longer videos, live streams and more complex editing. Time is ticking. And as is already apparent, these new-media platforms tend to drift from sanctuaries for short-form content to incentivising longer formats with advertising revenue. The most talked-about video on YouTube right now is a four-hour vlog about the ill-fated Star Wars hotel (currently on eight million views). At first populated by singular entrepreneurs and creative amateurs, the platforms tend to become colonised by companies who capitalise on the new media and align it with corporate structures. The new platform’s heyday is fleeting, the audience adjusts or moves on, and the cycle begins again.

The streams of old and new media very often cross in productive ways that involve re-imagining ideas with new language. When I curated a retrospective of Asta Nielsen for BFI Southbank in London in 2022, the first in nearly 50 years, I was pleased to learn that Die Asta has long been celebrated as an avatar of gender non-conformity on Tumblr (“#trans man hamlet yes! #i mean i know techncially thats not it but #okay its female actor playing a hamlet who was born female and #their parents raised them as a boy #idk if its against their will idk how hamlet feels about it #but i’ll take that trans male coded character thank you very much #and its gorgeous #hamlet”), and now on TikTok. She lives, and is venerated, in two distinct eras. Nanna Frank Rasmussen’s smart 2020 article praised her as a #BossLady, remarking on her considerable career achievements and using a modern hashtag to eclipse that terrible time barrier, fitting a vintage star into a contemporary archetype. New media has facilitated a new fandom.

Which brings us here. In 2010, after the first social media revolution had taken place, I founded this website, a blog called Silent London. Its stated purpose was to collate listings for silent film screenings in London, its broader intent was to share the love of silent cinema, though this, it soon became apparent, was pushing at an open door. The modus operandi was not to copy out texts from history books, but to acknowledge that there is an audience for silent cinema right now, who may be new to the subject, whose reason for viewing is not research or scholarship, and may not be motivated by a film’s place within the canon, nor its relationship to canonical filmmakers. They enjoy early and silent cinema for its own sake. Silent cinema is, among many other things, an evening’s entertainment. Its importance does not only reside in its centrality to film studies textbooks.

The readers of Silent London, I have learned over the past decade and a half, encompass scholars, archivists, filmmakers and other practitioners in related fields. But primarily, this blog speaks to cinephiles: moving-image hedonists, who enjoy silent cinema as part of a varied filmic diet. Which is not to say that silent film screenings are not special. The collective frisson of silent cinema spectatorship, an audience’s imaginative leap towards the screen, the dynamic energy and emotional emphasis of live accompaniment – Silent London readers revel in these pleasures. While we respect the work of the archivists and scholars who facilitate these screenings, Silent London exists within the space of contemporary film culture. And so, increasingly, does silent cinema itself. More and more, we recognise the aesthetics and technique of early and silent film bleeding from the archive into freshly minted contemporary cinema. The connections between films of all eras crackle in our minds and in the imaginations of the filmmakers we love.

So I try to erase the time distance. I write about early films not because they are old, but because they are so young. I don’t talk about old movies, but young cinema, those films that were made when the medium was new and its possibilities had not been fully mapped out. Young films do not yet have histories, but are bursting with faith in the future of the medium[2]. They have this in common with the best of contemporary cinema.

I take this approach when writing elsewhere on early and silent film, and as a critic I am also witness to the prevalence of silent cinema aesthetics in new films. Increasingly this phenomenon is my pet subject, especially in my monthly column for Sight and Sound (The Long Take), and on the tab on this site labelled “At the Talkies”. Related but not quite the same: for a while, Pete Baran and I hosted The Sound Barrier, a podcast devoted to finding connections between new releases and the silent archive – it was vastly enjoyable to record.

Visual storytelling abounds in cinema, but sometimes the references are more specific, the commitment to ditching dialogue firmer. You can take any one of a number of examples, from the Oscar-winning faux-silent The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius, 2011) to dialogue-free animations The Red Turtle (Michaël Dudok de Wit, 2016) and Robot Dreams (Pablo Berger, 2023), the elevated pastiches of Guy Maddin and the hands-on archival adventures of Bill Morrison, who takes silent cinema’s materiality as his central subject, to the traces of silent cinema style in the arthouse films of say, Miguel Gomes (Tabu, 2012, Grand Tour, 2024) and Alice Rohrwacher (Le Chimera, especially). Next week at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, Rohrwacher will be in dialogue with Juho Kuosmanen on the subject of The Future of Cinema (Silent) – and naturally, I have a ticket for that conversation. The best film of last year, Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, was essentially a silent film and a sound film, playing at the same time. The director has said as much himself, and that he has harboured aspirations to make a full silent film. The Fall (2019), covered on this site, was one short-form venture into the form. Or something like it.

But is it really a silent film, quiz the sceptics? This question is mostly beside the point. The postmodern magpie impulse leads us away from purism and into remix culture. We recently welcomed the re-emergence of Musidora via the revival of Irma Vep on TV with Alicia Vikander, following Olivier Assayas’s 1996 film of the same name starring Maggie Cheung[3]. I would love to your draw your oversubscribed attention to the mischievous appearance of Louis Le Prince as a supporting character in Marie Kreutzer’s Corsage (2022, pictured above) – improbably wielding a reel of celluloid and giving the young Empress Sissi an opportunity to express herself in a medium of self-portraiture far removed from the formality of a court painting in oils. The mechanics of an early film apparatus in the service of the imperial selfie. Young cinema references live again in gleefully anachronistic contexts.

As has been remarked before, this is happening alongside an explosion in the availability of early and silent film on DVD and Blu-ray, even on streaming platforms, and the growth in archive cinema festivals. These things are clearly related. We might trace this “silent film revival” back to the centenary of cinema celebrations in 1995, which reminded us all over again of cinema’s youth, the compelling beauty and strangeness of early film – the century looping back on itself like a reel.

So there are intellectual and practical reasons for the persistence of silent cinema style. But I would argue that there is also an emotional pull, drawing us back to the first decades of filmmaking. This is counter intuitive. When Billy Wilder made Sunset Boulevard (1950), and Stanley Donen made Singin’ in the Rain (1952), the memories of the silent era, and the fraught transition to sound, were still relatively fresh, barely a generation away. The filmmakers were excavating their own youth, their own back catalogues. Conversely, no one living today feels genuine nostalgia for the early film period. We don’t remember that far back.

However, I think there is a connection. We yearn for the new media excitement of ten or twenty years ago or more – the same sense of a moment captured in time emerges when we look at both. Whether the form in question is MySpace or Vine or YouTube vlogs, Facebook pokes, gifs, hashtags or Boomerangs. Ah, the days of landscape-oriented video. Or that particular format, the music video, corralled into an immersive exhibition practice called MTV and genuinely ubiquitous, now still as glamorous and sometimes expansively produced, but streamed singly online, or relegated to a “background screen” in a bar or hotel foyer. Who remembers renting a VHS, home-taping a movie off-air, or covertly watching a “video nasty”[4]? Laser discs, even. Or simply broadcast TV, in a choice of three or four channels. We have always been watching, and experiencing newness and loss.

Remember how we discovered, studied and adapted to the new forms, found ways to use them for our own amusement, our own conversations? We have become adept at learning to love and then learning to move on, from new media. The Artist, just like Sunset Boulevard, takes the loneliness of standing still while the world turns to a new novelty, as its central theme. Decasia, with its once carefully crafted images engulfed by decay, expresses this bereavement without saying a word. Sometimes, rarely, we find a form and stick to it, in defiance of fashion. Why is this blog still a blog, and a WordPress-hosted blog at that, when my peers have migrated to Substack, or pivoted to video? I must be old-fashioned, I guess, or simply nostalgic. Hands up if you remember when this site began, perversely on Tumblr? Or when Twitter – a platform that persists even now, but under a new name, with dangerous new rules, and diminished engagement – was integral to its growth?

When we look at early film we recall the ephemerality of once-new media: so many young cinemas, and one powerful pang. The joy of novelty and movement, experimentation and awkwardness, of discovery and reorientation and then the inevitable shock of absence. We understand the connection between our modern screen culture, and the early film period – but more importantly we feel it too. New media forms demand and swallow our attention, but their content is easily lost, and their existences short. This emotional link, as well as the artistic expressions that it provokes, is a rebuke to the idea of linear history. This is fine, because cinema time is always instantaneous. And cinema will always find a way to stay young. For a multitude of reasons, we are living in the silent film revival, and I find myself racing to document it.

Early cinema is trending in the 21st century, but how are we going to make the most of it?

————-

Curating Early Cinema Today – Domitor 2024

Why “early cinema” in the twenty-first century? Over the past several decades, there has been a global revival of silent film culture—from international festivals and archival research collectives to popular podcasts, blogs, and social media fandoms. Passionate communities of students, scholars, archivists, curators, artists, and musicians have rallied around the resurrection of movies made over a century ago. But what is the specific appeal of “early” cinema—as an aesthetic form, experimental impulse, and historiographic gambit—toward bringing silent film culture into contact with the possibilities and crises of the present? New media pose irresistible parallels with early film exhibition practices, epitomized by the recurrence of viral temporal loops and attraction-based spectacles. Yet there are logistical challenges to curating early films (which are often very short) as opposed to feature-length works. Beyond material considerations, how do the uneven politics of visibility and representation in early filmmaking (its radicality and racism, for example) speak to feminist, queer, decolonial, anti-racist, and other social justice movements today? Digitization has made the early film archive widely accessible—but unmanageably plentiful. Its contents encompass 4k nitrate scans, physical media collections, curated streaming databases, and the unmoderated recesses of YouTube and TikTok. How best to give method to early cinema’s madness by concocting playful, new conceptual categories for thematic and speculative curating? Most importantly, who are the audiences for early cinema today (beyond the usual suspects) and how can we (early film evangelists) work together to identify, curate, and contextualize an evocative range of programming and syllabi that will bring new publics into the fold?

Chair: Maggie Hennefeld. Participants: Elif Rongen-Kaynakçi; Kate Saccone; Grazia Ingravalle; Enrique Moreno Ceballos; Pamela Hutchinson

- Read more about the 2024 Domitor conference here – it was an excellent event.

- Silent London will always be free to all readers. If you enjoy checking in with the site, including reports from silent film festivals, features and reviews, please consider shouting me a coffee on my Ko-Fi page.

[1] For a commentary on the capitalist realities behind the apparently hobbyist jollity of TikTok comedians, see Maggie Hennefeld, Death by Laughter: Female Hysteria and Early Cinema (Columbia UP, 2024)

[2] For more on this distinction, see Young Cinema or Pamela Hutchinson, ‘Curating Young Cinema’, Feminist Media Histories (2024) 10 (2-3): 159–165,

[3] This excellent film was my gateway into a lifetime of silent film fascination

[4] Film such as Prano Bailey-Bond’s Censor (2021) appeal to this nostalgic itch, just as clearly as The Artist appeals to those who admire the aesthetics of silent Hollywood.

After Alice, Beyond Lois: Celebrating the Women Film Pioneers Project at MoMA

Some news is too good not to share, even if the Atlantic Ocean makes this a little inconvenient for me, personally. If you can be in New York later this month and next, I urge you to attend a particularly excellent birthday party.

The Women Film Pioneers Project, an impeccable resource for early and silent film history, has reached its 10th birthday. The brainchild of Jane Gaines, and managed by Kate Saccone, the WFPP has been doing the good work of balancing the gender books of film history for 10 years now, and this calls for a celebration. One that takes the form of a film season, curated by Saccone with Dave Kehr at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

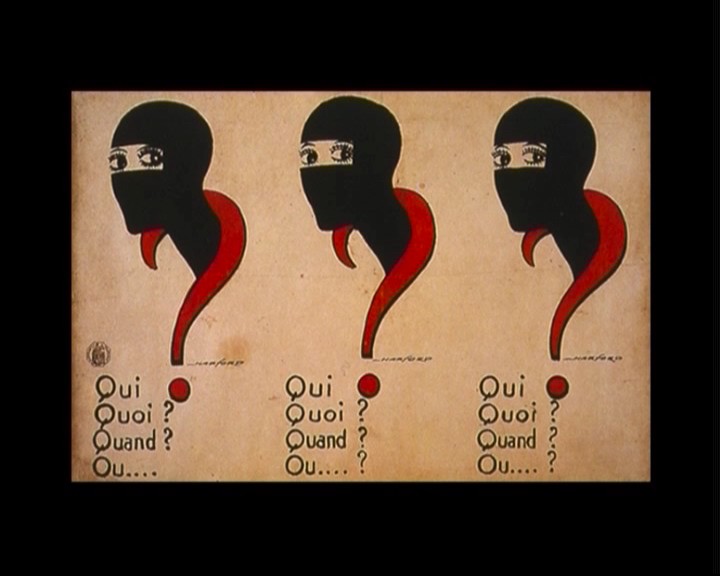

Continue reading After Alice, Beyond Lois: Celebrating the Women Film Pioneers Project at MoMAMusidora: Who? What? When? Where?

As I talked about Musidora in my Philip French Memorial Lecture last month, here’s a little more about the French filmmaker, in a short piece that first appeared in Sight and Sound magazine two years ago, in September 2019, following the retrospective of her work at Il Cinema Ritrovato.

“It is vital to be photogenic from head to foot. After that you are allowed to display some measure of talent.” Musidora, who wrote those words, is remembered as one of the true icons of silent cinema in her incarnation as Irma Vep in Louis Feuillade’s 1915 serial Les Vampires. However, there was more to her talent than her photogenic features, her white face and kohl-rimmed eyes and that famous slinky figure in a black body-stocking.

As revealed in a retrospective strand at the recent Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, the full range of Musidora’s career was fascinatingly diverse, feminist, ambitious and wittily self-reflexive. She was born Jeanne Roques in Paris on 23 February, 1889, and by the time of her death, aged 68, on 11 December, 1957, she had worked as a stage actor, singer, film star, novelist, journalist, producer, director and archivist, among other jobs. It’s doubtful that many of the cinephiles purchasing tickets at the Cinématheque Française in the 1950s would have recognised the woman who occasionally worked in the ticket booth as Musidora, the original screen vamp, muse to the surrealists and catnip to the moviegoing public in the 1910s.

Continue reading Musidora: Who? What? When? Where?Ritrovato Roundtable: Il Cinema Ritrovato 2019 podcast

The Bologna suntans are fading but the Il Cinema Ritrovato memories are still vivid. So Peter Baran and I were delighted to be joined on our latest podcast by academic and film programmer Eloise Ross, as well as filmmaker Ian Mantgani and writer Philip Concannon from the Badlands Collective. We’re chatting about our highlights, discoveries and duds from the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival – a feast of archive, vintage and restored cinema, spanning silent and sound films.

Maximum effort!

The Silent London Podcast is also available on iTunes and Stitcher. If you like what you hear, please subscribe and leave a rating or review too. The podcast is presented in association with SOAS radio by Peter Baran and Pamela Hutchinson.

Ritrovato Roundtable: Il Cinema Ritrovato 2019 podcast

If you want to get in touch with us about anything you hear on the podcast then you can post a comment below, or tweet @silentlondon.

- My report on the silent films at Il Cinema Ritrovato 2019 is online here.

- Read more about all these films in the beautiful festival catalogue.

- Read Jose Arroyo on Le Chat here.

- David Cairns was blogging brilliantly at Bologna as ever – work backwards from here, maybe.

- This year I was once again a judge on the Il Cinema Ritrovato DVD Awards – you can see a full list of our winners here.

- The 2020 dates are out: the next Il Cinema Ritrovato runs 20-28 June 2020.

- Follow the Badlands Collective – they do great things!

- Listen to the Cultural Capital podcast – follow that here.

- Watch out for more from Peter Baran on Freaky Trigger.

- Can’t wait for Next year? take a trip to Bristol for Cinema Rediscovered.

- The Under Capricorn symposium takes place on 5-6 September 2019 at King’s College London.

- I use Letterboxd, sporadically, so have some capsule reviews of Ritrovato films on there.

- Silent London will always be free to all readers. If you enjoy checking in with the site, including reports from silent film festivals, features and reviews, please consider shouting me a coffee on my Ko-Fi page

Silents in the Piazza: Il Cinema Ritrovato 2019

Buongiorno! I have just returned from a week in Bologna and while sadly I have no tan to show off, I did see a lot of silent films while I was there. What else is there to do in Italy?

As you may know, I was at Il Cinema Ritrovato last week – the international festival of archive cinema par excellence. You can read my tips for doing Ritrovato right here, but this post is all about the silent gems I saw while I was there.

First: a disclaimer. I approach Ritrovato like an omnivore, tasting a little of everything, talkies and all, so this is not an exhaustive report of the silent offering, just the ones that I especially enjoyed.

1928 and all that

Let’s deal with the giants first: Buster Keaton’s freshly restored The Cameraman (1928) and Charlie Chaplin’s The Circus (1928) won a flock of new converts at grand open-air screenings in the Piazza Maggiore. Especially the latter, which I think is one of the very finest of all the silent comedy features. Watch out for the Criterion edition later this year, with a booklet essay by your humble scribe. Continue reading Silents in the Piazza: Il Cinema Ritrovato 2019

Les Vampires: a dream of silent cinema

This is a guest post for Silent London by Tim Major, a writer of speculative and weird fiction. His short stories have been selected for Best of British Science Fiction and The Best Horror of the Year. His next novel, Snakeskins, will be published by Titan Books in spring 2019. Find out more at www.cosycatastrophes.com

There are moments when I experience a twinge of surprise that I’ve written a long-form non-fiction book about Louis Feuillade’s 1915–16 crime serial, Les Vampires. I’m a novelist and short-story writer rather than a film writer. While I love silent film, it’s far from my specialism. Even so, when I was invited to write a book for the Midnight Movie Monographs series from Electric Dreamhouse Press, Les Vampires was my first choice.

Les Vampires exists in a strange hinterland between the ‘cinema of spectacle’ and the narrative and montage techniques being developed concurrently by filmmakers such as DW Griffith. Nowadays Les Vampires is accepted as highly important in the canon – it laid the groundwork for many staples of crime films as well as the conventions of episodic drama now more likely to be experienced on TV – but it’s equally likely to be mentioned as an example of one of the world’s longest films, at seven hours. Frankly, I’m appalled that the serial gets referenced so much, but seems to be watched relatively little. Continue reading Les Vampires: a dream of silent cinema

Bernard Natan, Musidora and Alice Guy-Blaché: French pioneers remembered on film

You may notice the widget on the righthand side of this page, ticking down the days until this blog dispatches itself to Italy, to report from Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone. We have many reasons to get excited about the arrival of the world’s most prestigious silent film festival. There’s the debut of the lost-and-found Orson Welles short Too Much Johnson, the premiere of a new restoration of The Freshman with a score by Carl Davis, Italy’s first glimpse of Blancanieves, an Anny Ondra retrospective, a programme of Swedish silents, more treasures from the Corrick collection, Ukrainian classics, Mexican rarities, a strand devoted to Gerhard Lamprecht and much more.

I had a smile on my face this morning, however, when I learned that a documentary co-directed by none other than a fellow classic/silent film blogger – the marvellous David Cairns of Shadowplay – will be showing at the Giornate. Natan takes a look at the controversial life of French film-maker Bernard Natan, and the various scandalous assaults on his name. Natan was a Jewish French-Romanian film produced, who was at one time the head of the Pathé studio. Financial troubles, antisemitism and allegations that he was a pornographer degraded his reputation in the industry. His story ends on an even darker note – he died in 1942, in Auschwitz.

Cairns blogged about the film earlier this year:

Bernard Natan used to sign his films — literally, his producer credit was an animated signature inscribing itself on the screen. And then, as Natan’s reputation was destroyed and his company taken away from him, a lot of his films were shorn of their signatures. When the movies got re-released, it was considered embarrassing for their executive producer’s name to be seen. And during the Occupation, many Jewish filmmakers were quietly erased from title sequences.

Since then, Natan’s name has been restored to some of his films, and a few historians have attempted to restore his reputation. That’s the effort Paul and I hope to contribute to with our film, which should tell a dramatic and tragic story, shine a light upon some neglected corners of cinema history — but also help give Bernard Natan his good name back ~

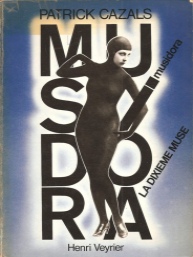

The film has already shown at several festivals, including Edinburgh and Telluride – and it plays at Cambridge film festival this week. The Pordenone festival will also be screening a documentary about another French cinema legend: Musidora: la Dixieme Muse. The documentary, by writer and filmmaker Patrick Cazals, promises to trace the actress’s career right form the early days of Vampires and Judex, to her work in later life as a producer and director as well as at Henri Langlois’ Cinematheque, positioning her as a cornerstone of French cinema as much as a legend.

So that’s a nicely themed double-bill at Pordenone for us to savour, but French cinema pioneers are in vogue right now – you can’t have failed to miss the successful Kickstarter campaign for the Jodie Foster-narrated Alice Guy-Blaché documentary. It has been a massive campaign, conducted enthusiastically and cannily across social media. The line they have been using is that Guy-Blaché’s name is forgotten now because she has been written out of history by her male colleagues and successors. That may be true for many film fans, but just like Musidora, her name is already well-known in silent cinema circles – if Be Natural is to redeem her reputation, it must spread her fame to a far wider audience. While certainly impressive, Be Natural‘s 3,840 Kickstarter backers represent a drop in the ocean. The movie looks like it could be great though – and it’s the popularity of the documentary, rather than the worthiness of its intentions, that will return Guy-Blaché’s name to global renown.

Catch Natan at Cambridge if you can, or if you have already seen it or Musidora, do let me know your thoughts below. There’s a Variety review here. You can also like Natan on Facebook. I have to say, I am looking forward to all three of these films.

PS: I think Lady Gaga, for one, has been mugging up on her early French film – spot the Méliès refs and Musidora costumes in her latest video, Applause