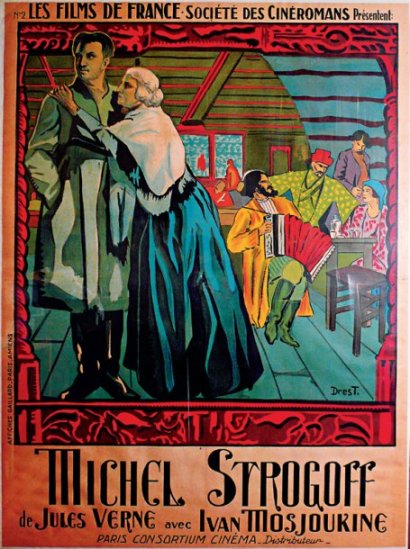

Get it together, people! We’re only on day two of the festival and it seems a collective mania has already descended. Call it camaraderie, call it cinephilia, call it cabin fever, but there was a feverish mood on Friday, for sure. I won’t criticise something that I admit I was part of but we should all know that somewhere the ghost of Ivan Mosjoukine is raising an immaculately painted eyebrow in our direction. He’s judging us, but silently, of course.

So the residents of Leicester may have heard wicked cackles emanating from the Phoenix art centre on Friday morning, because there were laughs a-plenty to be had, for the right and wrong reasons both. Forgive me for taking the films out of sequence, but I would like to introduce you to the second film first.

As I took my seat for Not For Sale (1924) I was whispering under my breath “Please be good, please be good …” And it was. This film is an out-and-out joy, with a classically British delicacy in its sentiment, humour and satirical bite. Those good vibes I was sending out were partly due to sisterly pride: the script is by Lydia Hayward, who wrote the H Manning Haynes adaptations of WW Jacobs stories that have so delighted previous iterations of this festival. I suppose I wanted a little more proof that she was crucial to their success. And Not For Sale, which is adapted from a novel by author and journalist Monica Ewer, provided it. This is a charming comedy, with an elegant structure, strongly written characters, sharp dialogue and yes, even a skein of feminism woven into its fabric. Toff Ian Hunter is slumming it in a Bloomsbury boarding-house run by the kind-hearted Anne (Mary Odette), and they fall in love … gradually. But when he offers a proposal, sadly he shows he has not left his old world and its shoddy values behind him. The central couple are adorable, but it’s the supporting characters (Anne’s lodgers, her rascally little brother and her theatrical sister) who make this a real ensemble treat. Plus, we had beautiful piano accompaniment from John Sweeney, so we were feeling incredibly spoiled. It boils down to this: the plot is preposterous but the characters, by and large are not, and so it has a grace and a truth often absent in romcoms …

Continue reading British Silent Film Festival 2015: Leicester letter No 2