More than 100 years ago, film-makers Mitchell and Kenyon advertised their services to the public with the line: “See yourselves as others see you.” A new film, shot last summer in London, offers us the opportunity to see ourselves, now, as Mitchell and Kenyon might have seen us. Londoners is a 21st-century “actuality”, comprising film shot on the streets of the capital, outside Arsenal’s Emirates Stadium, in Hyde Park and at the Notting Hill Carnival. The twist is that the footage was filmed on a 1915 vintage camera, an old-school hand-cranked machine.

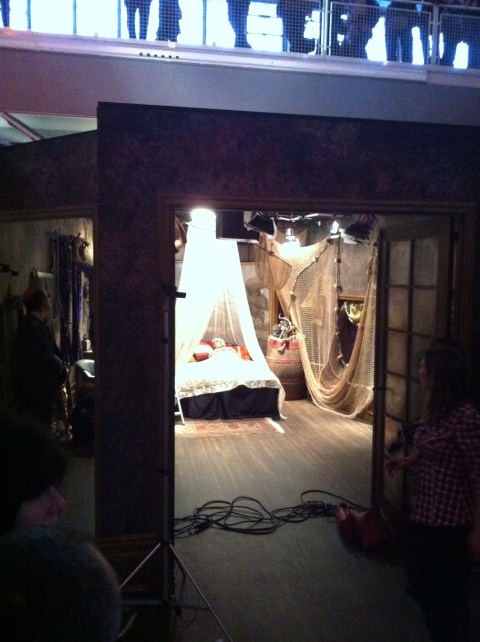

Director Joseph Ernst discovered the camera in a warehouse filled with old film-making equipment, and taking the Mitchell and Kenyon films as his inspiration, set out to record London circa 2011, but at 18 frames per second. As he told Wired.com, the people he photographed with the vintage camera were just as happy to be filmed as the customers of his Edwardian predecessors, and just as astonished by the technology. “Modern society finds no comfort in the digital camera. We shy away from them. We complain if someone points it in our direction. But if you bring out some spectacular relic from the past, people forget all that. They’re surprised that such a thing still exists and that it actually still works.”

And you can see that amazement in the film, which I was lucky enough to be granted a preview of. Londoners who might well be expected to be unmoved by the sight of a cameraphone, camcorder or iPad pointing in their direction, smile, point and nudge their neighbours when they see Ernst’s vintage machine. A Hell’s Angel dances an old-timey jig, a football fan guffaws and a wag at Speaker’s Corner mimics the cameraman’s movements – the the hand-cranking motion we all recognise from games of Charades. A group of photographers on Millennium Bridge snap the camera from all angles with their hi-tech DSLRs. The dancers at Carnival put on a display too, one that would probably have made the Edwardians blush.

But perhaps the Edwardians weren’t as stuffy as we think. There’s a uncanny, out-of-time quality to Londoners, with its faded, flickery footage of people who dress, stand and gesture just like us, but walk, thanks to the lower frame rate, with a hint of the jerky stiffness we associate with people from days gone by. It’s a reminder, if we needed one, that people don’t change very much at all over the years. Yes, the people in Londoners are more casually dressed, less formal, and overwhelmingly more racially mixed than in those Mitchell and Kenyon films, but they’re just as likely to hurry past or pose for a close-up, to smile or leer at the camera. The faces are the same. In a scene of commuters hurrying down the steps to a tube station, we’re drawn to a man who’s taking the descent a little slower, clutching on to the handrail, struggling to contain the tremors that are running through his body. It seems as if only the film-maker notices, as the crowd streams past him unaware, that the rush-hour journey is not the same for everyone.

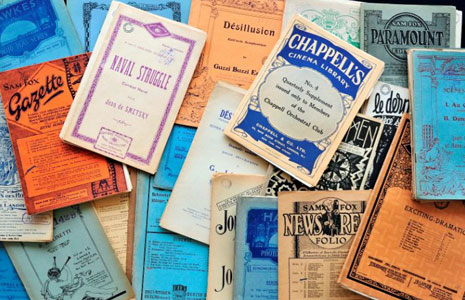

In fact, even when the film is joyous, as when primary school children are bouncing in front of the lens, Londoners strikes a mournful tone. The music, which is taken from a gorgeous Bat For Lashes track, sets the mood. But there’s more to this movie. At a time when we’re losing our grip on real film, and apps from Hisptamatic to Silent Film Director offer us to the chance to remodel our snaps and home videos as relics from another time, Londoners’ deliberately archaic, lo-fi construction offers a more powerful blast of nostalgia. In another hundred years, the technology this documentary uses will seem irredeemably quaint, but so too will its subjects’ clothes, their junk food and even their risqué dance moves. But a project such as this compresses the years and shrinks the distance between us and our forebears. Mitchell and Kenyon would feel right at home, and I hope we see something just like it in 2112.

You can find out more about Londoners, and see out-takes from the film, on the Facebook page at facebook.com/LondonersDoc