This is a guest post for Silent London by Neil Brand

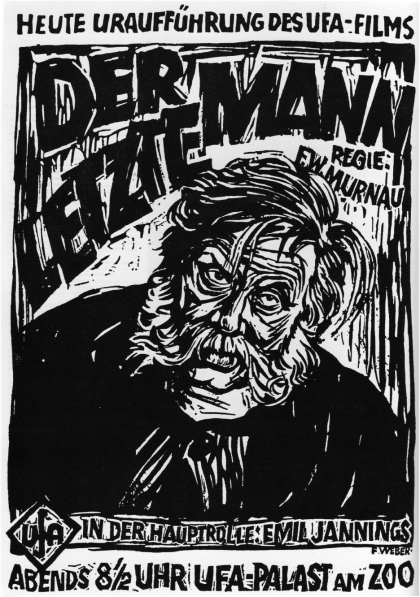

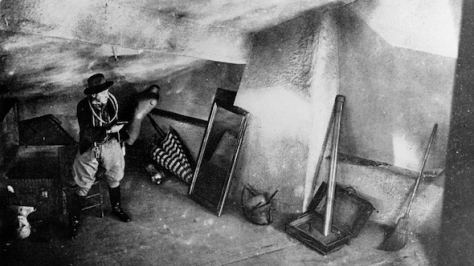

In 1925, Bram Stoker’s widow, Florence, won a plagiarism case against film producer Albin Grau over the latter’s 1922 chiller, Nosferatu. To be frank, Grau didn’t have a leg to stand on – he had applied for a licence to film Dracula, been refused by Florence and gone ahead with filming anyway, changing a few character names. This hardly distanced his film from Stoker’s Dracula, whose plot he had lifted lock, stock and barrel for Nosferatu and Florence successfully sued to get his company closed down and every copy of the film destroyed. Thanks to one vital copy, lodged at the time in the US where Stoker’s novel was already out of copyright, we still have the movie and every print now available descends from that one saved positive.

But I’m beginning to think that a skilful lawyer could actually have argued Florence down. Over a lifetime of playing this masterpiece I have noticed that in two vital areas scriptwriter Henrik Galeen and director FW Murnau actually created a new monster that Stoker would barely have recognised – firstly Van Helsing is a small-part character who is in no way responsible for Dracula’s destruction; secondly Nosferatu, minus Dracula’s brides, only has eyes for only one woman – Mina Harker. And it’s beauty that kills the beast.

I’ll go further – Nosferatu/Orlok is not Dracula, but director FW Murnau himself – with the result that today’s vampires flitting through Twilight and The Diaries are the children, not of Stoker’s night, but of Galeen and Murnau’s. And the music they make is very different.

The magnificent central section of the film depicts the vampire heading towards Whitby/Wisborg on board ship, disposing of the crew one by one like some hideous onboard buffet while Harker/Hutter plods back home across the mountains. Waiting on the beach is Hutter’s wife, the strange, other-worldly Mina, staring out to sea and during her sleepwalking catatonia delivering the devastating line: ‘My lover is coming!’

But which lover, the Count or the Husband? Let’s look at what has brought them all to this point – Orlok has seen Mina’s picture and is about to gorge himself on Hutter for the second night running. Mina, staying with friends who have rescued her from a perilous walltop sleepwalk, suddenly sits up in bed with a cry – across a single shot-cut (but miles of the Carpathian Mountains) Orlok freezes in mid-bite and turns to face the direction of her ‘voice’ – off camera right. In Witold, she slumps. In Transylvania, he moves away, his meal untouched. The next time we see him moving he is heading away from the castle and towards Mina, bearing his coffins. From then on it is as if she is already under his power – and, I would argue, he is under hers.

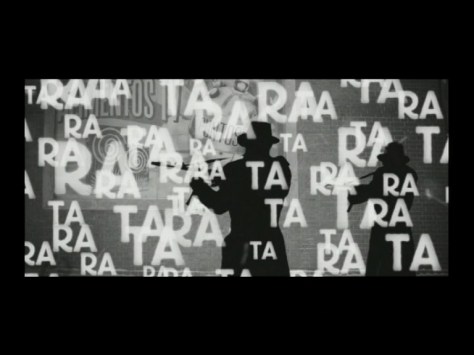

It is impossible to play Orlok’s arrival in Whitby/Wisborg as anything but heroic – the beautiful shot of the ship sailing itself to the dock; the scuttling figure with the coffin stopping outside Mina’s house for a brief smile and his first head-and-shoulder close-up in the movie; then the final river trip, standing proudly in a supernaturally powered rowboat, which deposits him at his new property where he enters by melting through the locked doors. No wonder Herzog chose Wagner for that sequence in his Nosferatu 70 years later. Orlok is a conqueror claiming his kingdom, from which he will stare balefully at Mina’s window while his rats destroy the city. And we are now, however unwillingly, rooting for him.

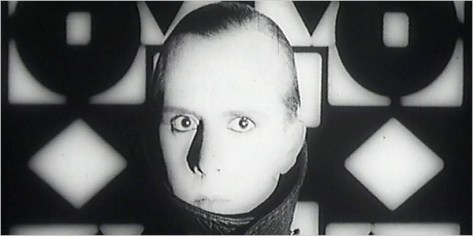

Murnau, by all accounts promiscuously gay and self-conscious about his appearance, obviously loved his vampire with the outsider’s love of a soulmate gifted with powers he can only dream of. Every flesh-and-blood male character in the film is weak or deluded; Hutter himself can only sit feebly by while Mina takes the strong course in dealing with both infection and infector. But as she makes up her mind we see Orlok imprisoned in his palace imploring her attention with a look that can only be described as heart-breaking. When she acquiesces, he comes to the feast like Don Juan triumphant, the shadow of his bony fingers enclosing, not her neck but her heart, which he squeezes as she writhes beneath him. Herzog would provide the perfect closure for their nuptials, Orlok looking up from her throat at the dawning light, only to have her draw his head gently back to her neck with the gentlest of arm-movements.

Audiences new to the film always laugh at the opening and the speeded-up actions, but it is a wonderful tonic to hear the silence descend as Murnau and his vampire exert their power. I have never been able to play triumph at the Nosferatu’s demise because we have been taught by Murnau to admire and pity him as well as fear him, and in the last thirty years Herzog, Coppola and Joss Whedon have all followed Murnau’s lead. Genius that he was, Murnau made the connection half a century before the rest of us did – we know Orlok because he is us.

Every silent film is an invitation to the musician to tell their version of the story and, yes, “Nosferatu, the Love Story” is a spin, one of many that could be applied to this great film. But here’s my point: treating it musically as a horrific love story opens vistas of new insight on this masterpiece that are vastly greater and more rewarding than the simple terrors of the night. And when the tension between horror, lust and desire is working, one can almost hear the new blood coursing through the vampire’s veins …

Neil Brand

Nosferatu is now on theatrical release, from Eureka Entertainment, screening at the BFI Southbank and many other venues around the country. Eureka will release Nosferatu on DVD/Blu-Ray on 18 November 2013. Pre-order here