So, last week, I found myself watching some early films in the BFI Southbank. Same old, same old, you might think. But these early films were being shown on massive MTV Cribs-style tellies in the BFI foyer. And while many of them were from the Mitchell and Kenyon archive we know and love, they were unseen treasures, having been gazed upon only by archivists during the past century.

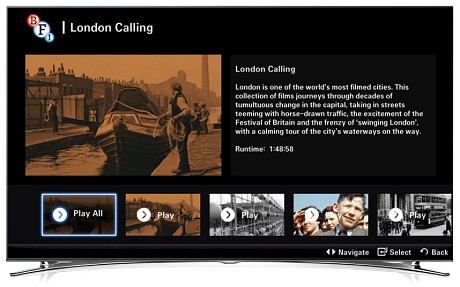

This unexpected alliance of Edwardian content and 21st-century technology has come about via the BFI’s new app, developed as part of the Film Forever project. It’s an app for Samsung Smart TV and Smart Hubs, and it allows viewers access to a treasure chest of film-related content, including a free Film of the Week (kicking off with A Zed and Two Noughts), interviews with film-makers, documentaries, and a whole heap of archival delights, including the M&K films. There will also be footage of events and interviews from the London Film Festival appearing when that all kicks off in October.

The archive goodies are separated into a variety of strands: London Calling and Cabinet of Curiosities, among them. There are silents across most of the ranges – many you’ll be familiar with, such as Daisy Doodad’s Dial or Wonderful London. It’s the Mitchell & Kenyon films that stand out though – they’re in a rather lovely collection called Edwardian Summer. There’s an hour and a half of footage here, a good hour of which is unseen. Robin Baker, the head of the BFI archive, calls these films: “Cinematic gold – you couldn’t get much more important.” What’s so vital about these short films, he explained, is that the “humanise the past”. They certainly captivated the crowd at the BFI.

You can see Blackpool in May 1904, with formally dressed holidaymakers parading on the pier or riding trams. There’s a Punch and Judy show, captured in Halifax in 1901 – your eye may be caught by the frisky puppy getting rather too close to the puppets, but don’t miss the plume of smoke that reveals a train station in the rolling hills behind the main event. A man in drag falls off a donkey (twice) in Hipperholme, West Yorkshire in 1901; Preston celebrates its Whit Fair in 1906. Delightfully, footage of the Chester Regatta delivers shots of boats gliding elegantly down the River Dee in the long hot summer of 1901. Watch a little further and you’ll discover a few courting couples doing what courting couples do in those very boats.

There’s silent London on show too – elsewhere in the package you can watch street scenes of Hoxton approximately 80 years before it became cool , for example.

I think it’s all gorgeous – I would like to sit down and watch all of the M&K treats in full, and there are some non-silent delights both sublime and ridiculous available too, including a Dufaycolor screen test featuring Audrey Hepburn and a public information film from the 70s starring Keith Chegwin. So this is wonderful news for those of you have, or are thinking of buying, a Samsung Smart TV, Hub or Blu-Ray player. It’s also good news for the rest of us. We may have to be a little patient, but as more of the BFI’s wonderful archive is digitised we can look forward to their films being made available in more ways. BFI apps for everyone please: not just on smart TVs, but on smartphones and tablets, perhaps?

Want to read more? Peruse the press release on this handy PDF.