Christmas is a time for happy endings. And box sets too, to be honest. Last year I posted about an ambitious new project from Kino Lorber – a box set of early work by African-American film pioneers. Films that were funded, produced, written, directed by and starring people of colour. These were films we have had precious few chances to see, or less than that, and they were going to be restored, and where appropriate, rescored. Not easy.

The first happy ending is that Kino pulled it off – and if you supported the project on Kickstarter, you may well have received a parcel this summer containing a shiny set of discs and a thick booklet of essays by Paul D Miller (DJ Spooky), Charles Musser, Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, Rhea L Combs and Mary N Elliott.

For those who didn’t have the cash to pledge at the time, or who can’t play imported discs, the BFI has stepped in to create another happy ending. This Christmas, the BFI has released its own matching version of the box set for the UK– and this isn’t so much a review as a recommendation.

This collection, The Pioneers of African-American Cinema, comprises five discs, with more than 20 hours of material, ranging from 1915-1946, with archive interviews from much later. There are feature-length musicals, war movies, evangelical films, anthropological footage shot by writer Zora Neale Hurston, amateur actualities by an Oklahoma Reverend, several works by Oscar Micheaux, and much more on these discs.

Watching these films is revelatory. In fact, just browsing the list of titles is an education. These films represent an obscured history of African-American filmmaking, an alternative film industry that existed largely separate to but alongside Hollywood, and a survey of African-American culture in the first half of the century. Many of these films directly address social issues, or comment slyly on Hollywood whitewashing. And many of them deal directly with faith and religion, from full-on cinematic sermons to the posturing preachers that so often appear in Micheaux’s films. As James Bell writes in his comprehensive review of the set in this month’s Sight & Sound: “Its significance for expanding a wider understanding of American cinema history can hardly be overstated.”

Continue reading The Pioneers of African-American Cinema review: an ambitious and excellent release

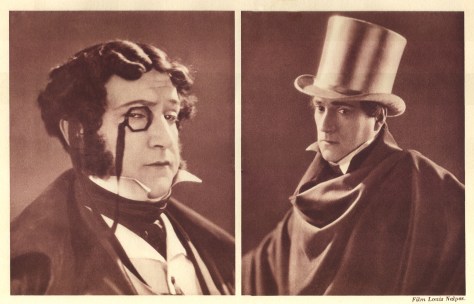

However, nothing can tear me away from my Who’s Guilty? morning treats, which have me more hooked than any soap opera. Yet again Anna Q Nilsson got married in haste (to the always-appealing, imp-faced Tom Moore, the son of the newspaper editor investigating her senator father’s corrupt affairs) and repented in haste too, as a lawsuit for abduction revealed a harsh truth about her childhood that led her straight to the brink. The brink of the lake that is. Thanks A Trial of Souls (1916) for that early morning anguish.

However, nothing can tear me away from my Who’s Guilty? morning treats, which have me more hooked than any soap opera. Yet again Anna Q Nilsson got married in haste (to the always-appealing, imp-faced Tom Moore, the son of the newspaper editor investigating her senator father’s corrupt affairs) and repented in haste too, as a lawsuit for abduction revealed a harsh truth about her childhood that led her straight to the brink. The brink of the lake that is. Thanks A Trial of Souls (1916) for that early morning anguish.