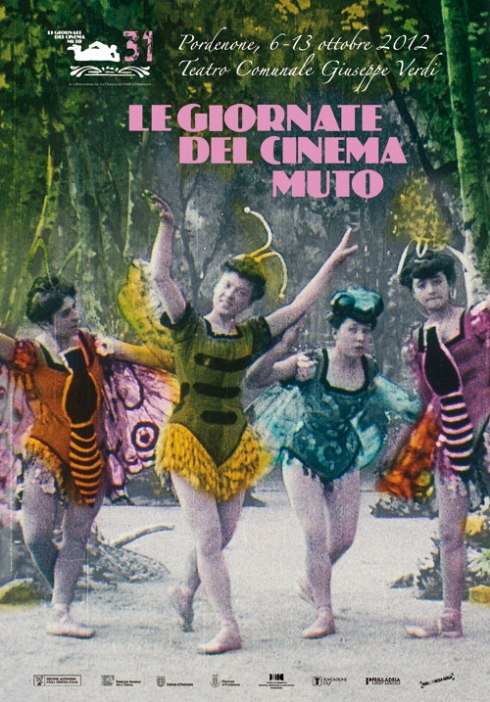

As you know, this year the British Silent Film Festival has taken a year off – but luckily for us, it’s the kind of year off where two all-day events still go ahead. Just to keep things ticking over, as it were. So last weekend there was a symposium on British silent cinema, held at King’s College London and organised by Dr Lawrence Napper. The following day the Cinema Museum hosted an all-dayer of screenings, themed on the tantalising idea of “sensation-seeking”.

I attended both events and while it didn’t feel like the festival was running, it was a real treat to be immersed in British silent film in this way. Let’s hope the festival returns back to full strength next year.

The papers at the symposium were limited to 20 minutes apiece, but covered a wide range of topics, from Edwardian theatre to state censorship to international co-productions to saucy novels. One hardly knows where to begin.

There were two papers with a theatrical bent: Ken Reeves’s dip into musical comedy theatre and its links to silent film concluded with some ideas for “crossover” events that would mix theatre, film and audience participation to spread the love about early British cinema. Audience participation? Reader, I sang. Very badly. Theatre historian David Mayer’s unforgettable presentation played and replayed the same baffling scrap of film as he uncovered the truth behind its creation. The scene of a waterfall bursting its bank and bringing down a bridge (and a couch and four) was, it turned out, not shot on location but on stage at the London Hippodrome in 1902, where a collapsible stage could be dropped and filled with water to create watery scenes. There was more – involving elephants on a slide. Elephants. Read more here.

Lucie Dutton, sometimes of this parish, also talked about the stage, presenting a history of film director Maurice Elvey‘s early career – in theatre in London and New York, before moving into the pictures with his star Elisabeth Risdon. She was followed by John Reed from the National Screen and Sound Archive in Wales, who took us through the production, loss, rediscovery and restoration of Elvey’s landmark film, The Life Story of David Lloyd George. Intriguingly, Reed pointed out a few instances in which Elvey could be seen in the film, waving a handkerchief and appearing to direct the action. Could this be because in these scenes the prime minister was played not by Norman Page but by Lloyd George himself? It’s an enticing thought.

Another famous British director was under the spotlight – one even more renowned than Elvey. Charles Barr presented on what we do know, and what we don’t, about the first film that Hitchcock ever shouted action on: Always Tell Your Wife. It’s an adaptation of a stage comedy starring theatre veterans Seymour Hicks and Ellaline Terriss and it seems the director fell out with his inflexible actors and therefore a “fat youth” from the props room was elevated to the job. You may struggle to see bold Hitchcockian strokes in what we have left of the film (which screened at the Cinema Museum on the Saturday), but we do have the director’s handwriting, unmistakably, in an insert shot of a telegram.

Far less well known than Hitchcock, but fascinating to hear about, was showman-turned-film director Mark Melford. His name, just like most of his films, may be lost to time, but Stephen Morgan attempted to flesh out his story, taking his cue from a Bioscope blogpost of 2007 that posed the pertinent question: “Who needs films to write film history anyway?” We did see a clip from the recently rediscovered romp The Herncrake Witch, directed by and starring Melford (amended, see comments) as well as being based on one of his own comic operas and also featuring his daughter (Jackeydawra, named thus due to her parents’ love of Jackdaws. True story). The story of the Melfords was hugely entertaining, but Morgan concluded by making the hugely important point that the study of lost films and forgotten film-makers is vital to a full understanding of the silent film era as a whole.

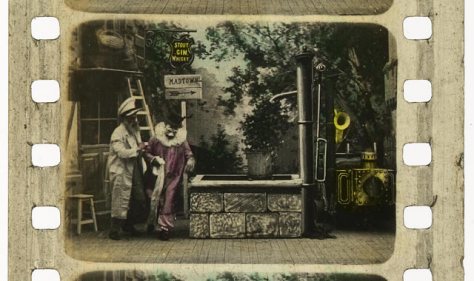

And of course, one never knows when a lost film will suddenly become an un-lost film. It happened to The Herncrake Witch and The Life Story of David Lloyd George after all. And it wasn’t so long ago that a treasure trove of Mitchell & Kenyon works was unearthed, giving us an invaluable glimpse of (mostly working-class) Edwardian Britain. In one of the day’s most diverting 20-minute segments, Tony Fletcher played a selection of Mitchell & Kenyon’s fiction films, while explaining a little more about them. The films were comedies, often chases and knockabout stuff, all with a backdrop of industrial northern England – factory gates, brick kilns and terraced streets. I particularly liked the mischievous snow comedy and the animated intertitles in a short called (I think) Driving Lucy.

More comedy, but this time of the you-couldn’t-make-it-up school: Alex Rock put recent Leveson revelations in the shade with a paper on the Metropolitan Police’s tangled relationship with the film industry. Its rather heavy-handed Press Bureau, founded in 1919, was popularly known as the Suppress Bureau. You can guess why. Rock’s paper traced the development of an official documentary film, supported by the Met, called Scotland Yard, and the squashing of another, based on the memoirs of a former detective.

The correspondence of public servants baffled, outraged or simply dismissive of the “movies” is unexpectedly entertaining, and never more so than in Jo Pugh’s paper on the official military response to Walter Summers’ The Battles of the Coronel and Falkland Islands. I could barely keep up with the information he was imparting, partly because I was giggling so much. Really. The good news is that we should hear more from Jo’s research and more about the film too as a little bird tells me a full restoration (possibly in time for next year’s Great War centenary) is in process.

Continue reading The British Silent Film Weekend 2013 – reporting back