Birds Eye View is one of Silent London’s favourite film festivals – a celebration of female film-makers with an exceptionally strong and musically adventurous silent cinema strand. Last year, even though the festival was on haitus, the Sound & Silents programme brought us a selection of newly scored Mary Pickford films. This year, in keeping with the overall theme of the festival, the screenings have an Arabian flavour.

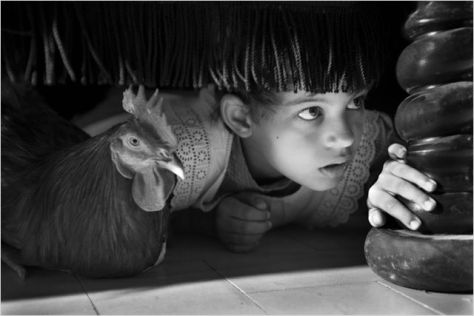

The two films in the Sound & Silents segment are, to be frank, German – but the first, Lotte Reiniger’s trailblazing cutwork animation The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) is based on a story from 1,001 Arabian Nights, as also, perhaps more loosely, is the second, Ernst Lubitsch’s boisterous harem farce Sumurun (1920). Achmed, widely acknowledged as the first animated feature film, and still as elegantly beautiful today as in the 1920s, probably needs no introduction from me.

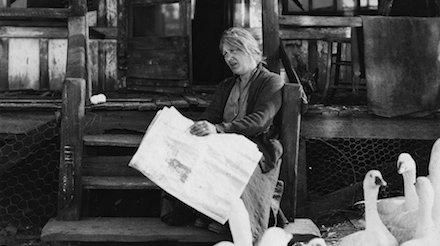

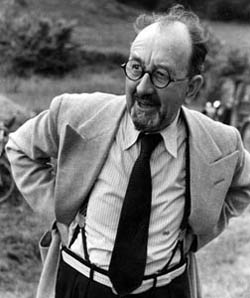

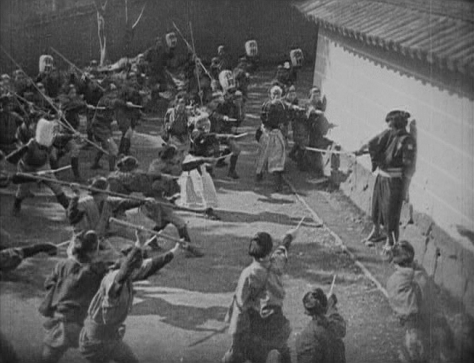

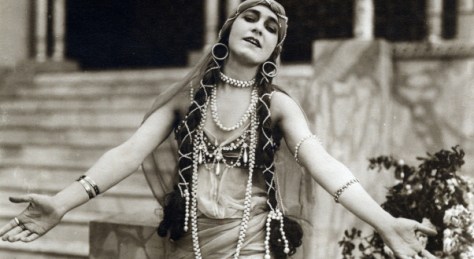

The latter film is a slightly guilty pleasure of mine – a rather well-made romp, enlivened by the sinuous presence of the young Pola Negri, and the more demure charms of Swedish ballerina Jenny Hasselqvist. Lubitsch himself appears as a leery clown with hunchback, but his real star turn is behind the camera, crafting a fast-paced and vivacious comedy out of unpromising material. Sumurun had been a stage hit for Max Reinhardt’s company in Berlin, and Negri had starred in both that production as well as one back in her hometown of Warsaw – perhaps it’s therefore no surprise that this film is so slick, with such larger-than-life performances, including Paul Wegener as a bully-boy sheik. I will concede, of course, that it is rarely, if ever, politically correct.

Sound & Silents is as much admired for its musical commissions as its programming, and it’s intriguing that these German Arabian pastiches will be accompanied by scored from musicians whose roots lie in both Western Europe and the Middle East – British-Lebanese Bushra El-Turk and Sudanese-Italian Amira Kheir.

Multi-award-winning contemporary classical composer Bushra El-Turk creates a new work for a chamber ensemblecombining classical Western and traditional Middle Eastern instrumentation, accompanying The Adventures of Prince Achmed, the world’s first feature-length animation. Currently on attachment to the London Symphony Orchestra’s Panufnik Programme, British-Lebanese El-Turk’s acclaimed work has also been performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra and London Sinfonietta.

Singer, musician and songwriter Amira Kheir blends contemporary jazz with East African music for a multi-instrumental 5-piece band, scoring landmark fantasy-drama Sumurun (One Arabian Night). Kheir has recently won acclaim for her ‘beautiful and fearless’ (Songlines) first album and her BBC Radio 3 and London Jazz Festival debuts.

Initially at least, the Sound & Silents screenings will be held in London and Bristol. Bushra El-Turk’s score for The Adventures of Prince Achmed premieres at a screening at the Southbank Centre on Thursday 7 March, with a second performance on Friday 5 April at the Barbican. Sumurun plays with Amira Kheir’s new score at BFI Southbank on Thursday 4 April and will then show at the Watershed Cinema in Bristol on Sunday 14 April. Click on the links for more information and to book tickets. Find out more about Birds Eye View here.