Jean-Luc Godard felt film-makers should be free to rearrange the beginning, middle and end of their scenarios. In 1903, Edwin S Porter left it to the projectionist. Scene 14 of his The Great Train Robbery, according to the sales catalogue, “can be used either to begin the subject or to end it, as the operator may choose”.

The Great Train Robbery is one of cinema’s earliest westerns, and something of a breakthrough in the development of narrative film editing. Porter’s ten-minute movie cuts between simultaneous action in different locations, more economically than in his previous work The Life of an American Fireman (1902), and the drama gains urgency from its use of location shooting, camera movement and frequent eruptions of violence. It is based loosely on Scott Marble’s 1896 play of the same name, and also, it has been suggested, a true story from 1900, when Butch Cassidy’s Hole in the Wall gang hijacked a train on the Union Pacific Railroad. The outlaws steal the mail and rob the passengers, exploding a safe and killing three men in the process. In real life, the Hole in the Wall Gang evaded capture that day, but in Porter’s film a posse of locals pursue the bandits on horseback, track them to a hideout in the woods and kill them in a shootout.

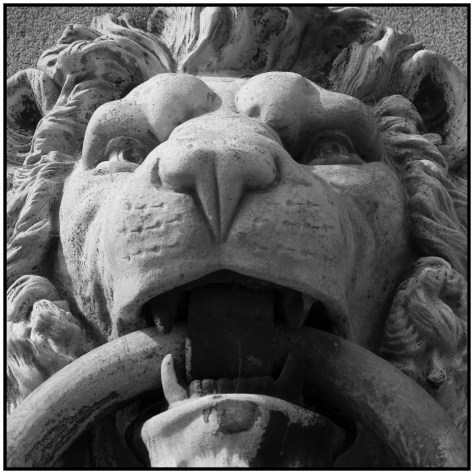

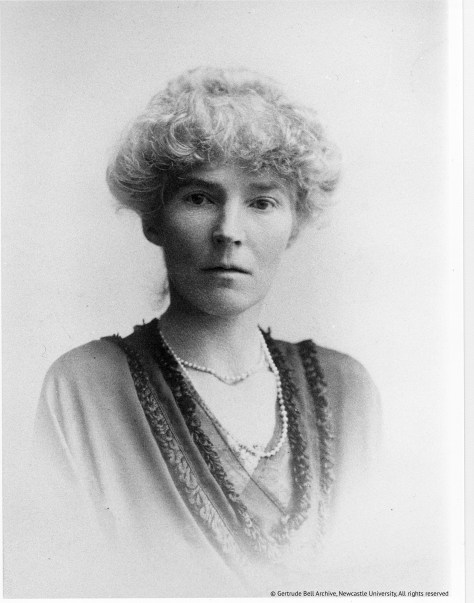

In scene 14, actor Justus D Barnes, who plays a member of the film’s bandit crew, faces the camera square-on, draws his revolver and fires six times in the direction of audience. With the gun’s chamber empty, he continues to squeeze the trigger, suggesting carelessness, desperation or an overzealous kill impulse. His impassive face suggests the last option is correct. The intended effect, according to the catalogue, which is what we have in lieu of a screenplay, is that Barnes is firing “point-blank at each individual in the audience”. It’s an especially violent act, both in real terms, and cinematic ones. The narrative momentum of the film is cast aside, then the fourth wall of the screen is broken by his gaze, only to be further ruptured by his bullets. Placed at the opening of the film, it might act as a trailer for the shoot-’em-up action to come. As a coda, it’s a warning to the audience that it’s a wild world out there, and the violence continues even after the case in the film’s title has been closed.

That’s perhaps why the version of the film that has been handed down to us places Barnes at the end, a jolt of terror as disconcerting as a hand bursting from a grave. Martin Scorsese borrowed the shot for the ending of Goodfellas (1990), submerging a trigger-happy Joe Pesci into Ray Liotta’s farewell to “the life”. In that film, the bullets can be read as an assassination threat (Liotta’s Henry Hill has ratted out his fellow wise guys to the FBI) or a guilty conscience, troubling the protagonist with memories of past bloody deeds. But just as in Porter’s film, Scorsese is addressing the audience, not the internal logic of the film. With these gunshots, Goodfellas acknowledges its place in the history of the cinema’s glamorisation of violence, a process that comes full circle when Hill’s closing monologue states that gangsters were “treated like movie-stars with muscle”.

But what does Scene 14 do for The Great Train Robbery? Porter is serving his audience the thrill of screen violence two ways. The portrait of Barnes in character (perhaps a reference to a Wanted poster) is a remnant of the Cinema of Attractions, but within a narrative film. In order to contain all the action in the frame of a mostly fixed camera, The Great Train Robbery relies on long shots, often with the outlaws’ backs to the camera, so we can see their crimes as they commit them. Scene 14 adds spectacle to the storytelling, and character too. That sales catalogue bills it as a ”life-size picture”, but on even the scantiest Nickelodeon screen, it would be far bigger than that. It gives us a long cool look at one of the outlaws before he fires, and then reveals his face again and again as the smoke from each gunshot disperses.

There’s another moment of spectacle in the film, a saloon scene in which the Wyoming locals perform a conventional group dance, and then a flashy “tenderfoot” routine, with “Broncho Billy” Anderson picking up his toes to avoid gunfire (there’s a nod to this Western turn in Goodfellas also, when Pesci’s character yells “I’m the Oklahoma Kid!” and shoots at Spider’s feet). The dance sequence serves as an introduction to the good guys who will chase the robbers down; a messenger interrupts the jig to share the news of the robbery.

If you compare these two pauses in the narrative pace of The Great Train Robbery, logic would dictate that Scene 14 should open the film, by way of announcing the gang. But in this early film, the trailblazer for so many movie westerns to come, narrative sense comes second to the thrill of action. The posse may have defeated the bandits, but as Barnes keeps firing the myth of the outlaw endures.