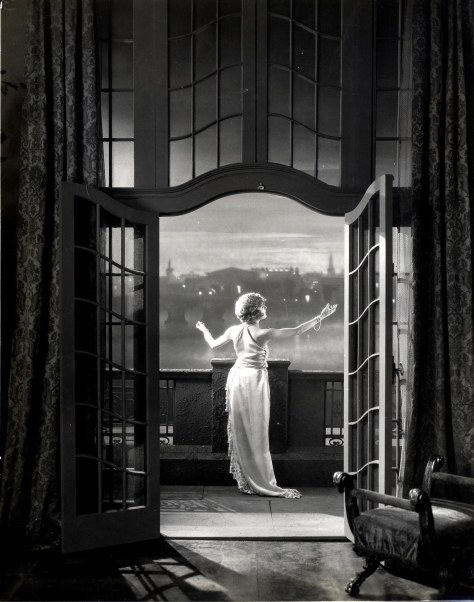

Synthetic Sin (1929) is an artefact from a time long gone. That is to say that this film is delightful, glamorous, witty … And they really don’t make them like this any more. It’s typical of this movie that the title is a roaring twenties in-joke, a bit of jazz-age wordplay on “Synthetic Gin”. That’s not a phrase you hear too often these days, but this prohibition-era film sloshes with bathtub hooch. In fact, this is the kind of wisecracking romp where a gal can say to a fella: “Let’s you and I make hey-hey while there’s moonshine!”

When the twenties roared, there was mischief to be made. In the inner cities, in real life, gangsters took advantage of the prohibition laws to make plenty of illicit cash hawking illegitimate booze. But in the movies, and in the anxious imagination of Middle Americans, the flappers, a new breed of confident young women with bobbed hair and short hemlines, were wreaking just as much havoc.

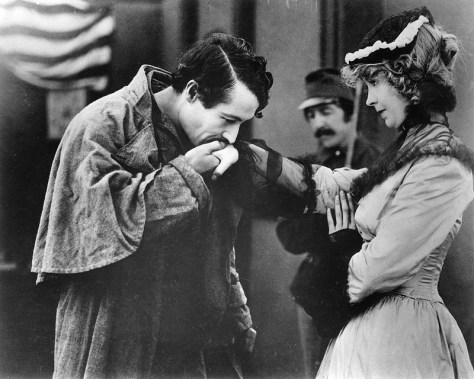

Synthetic Sin has all the hallmarks of a classic flapper film, even though its heroine, aspiring actress Betty Fairfax, is really quite an innocent. Betty is played by Colleen Moore, an impish natural comedienne who was the first of Hollywood’s bright young starlets to bob her hair and embody the newest, freshest way to negotiate the path between girlhood and womanhood. If any writer encapsulated the spirit of the Jazz Age, it was F Scott Fitzgerald, and he doffed his fedora to our star. “I was the spark that lit up Flaming Youth,” he said. “Colleen Moore was the torch.” And if you love Louise Brooks, Clara Bow or Jean Harlow, then you need to know Moore.

Preternaturally youthful and vivacious, Moore defined the flapper, the modern, sexually liberated young woman, in terms that high-school girls could love and emulate. After Moore’s mother cut her hair into her trademark fringed bob (“whack, off came the long curls. I felt as I’d been emancipated”), teenage girls across the US rushed to the salon. She was unthreateningly friendly and funny, but a beauty too. Moore has a cute charisma that works instantly on the audience, like a fast-acting drug. She is both irresistible and unforgettable – and she was a huge star in the 1920s. But the sad fact is that many of her films have now been lost, which means that most people don’t know her work at all. Synthetic Sin itself was only recently rediscovered and restored. So this film is a very precious chance to see Hollywood’s foremost flapper in action.

“Moore created comic heroines who are as engaging in their failures to be glamorous as they are in their often accidental triumphs in love and career,” wrote Molly Haskell. That’s Synthetic Sin in a nutshell.

Here Moore plays a young girl desperate to grow old too quickly, to become a “woman of the world” with the necessary life experience to be a serious dramatic actress. All flappers want to push the boundaries imposed by their old-fashioned parents, so Betty runs away from her comfortable home to a fleapit hotel in the big city, in the name of art, and of love. The audience is in on the joke from the beginning: Betty is wonderful just as she is. Her improvised show at the family piano early in the film is Grade A comedy, and the steps she takes to widen her horizons bring her into dangerous territory: grubby, sleazy, violent. A place where this flapper might just encounter a gangster or two.

Continue reading Synthetic Sin (1929): Colleen Moore and the joyful noise of the Jazz Age →