Controversially, I have been known to say that London is the centre of the silent film universe. You may think I’m biased – and you would be right. But this November, I will be feeling pretty smug. The most audacious of all silents, Kevin Brownlow’s restoration of Abel Gance’s epic Napoléon, will screen at the Royal Festival Hall in London – accompanied by the Philharmonia orchestra, conducted by Carl Davis as they play his masterful score.

It couldn’t be more convenient for me. I’ll hop on the tube for 25 minutes, grab a coffee and spend all day absorbed in a cinematic masterpiece. But I’ve already heard whispers from fellow silent film fans in the States, in Canada, in continental Europe and yes, even places-in-Britain-that-are-not-London, that they may want to sample the Napoléon experience too. It’s a dream come true – a world of silent cinema aficionados in this fair city, under one roof.

This video, advertising last year’s California screenings of Napoléon, should help you to understand why it’s worth the airfare.

You’re tempted, aren’t you? Therefore, in the spirit of welcome, for those of you who haven’t been to the Big Smoke before, or at least not since Napoléon last played here in 2004, here’s my 10-point guide to making the most of your trip, Silent London-style.

1. Location

The nearest station to the Royal Festival Hall is called Waterloo. No, really. You couldn’t make it up. Embankment station is also pretty handy, and there are several bus routes that pass by too. The RFH is part of the Southbank Centre, a large arts complex on the south bank of the River Thames, an area imaginatively known as the “Southbank”. Waterloo is a good station to aim for: the Northern, Jubilee, Bakerloo and Waterloo & City lines all pass through, as well as several mainlines from the suburbs and the south-west of England, if you’re not staying in town.

If you are travelling from the continent, bear in mind that it’s no longer the place where the Eurostar arrives though – that’s Kings Cross St Pancras (take the Victoria line southbound and change on to the Bakerloo line at Oxford Circus).

You may also like to know that many of the scenes in the silent film Underground, recently re-released by the BFI and available on DVD in June were filmed at Waterloo. And this scene featuring a hapless Guardian journalist from The Bourne Ultimatum too. If you walk over from Embankment, you get to cross the Hungerford bridge though, which is quite a treat for those who appreciate a good bridge.

The Southbank is really quite a groovy part of London, so if you’re around for a few more days, you may want to explore further – stroll along the front, and visit the amazing Tate Modern, Shakespeare’s Globe, the National Theatre or the Hayward Gallery. There’s lots of sleek but brutal concrete, gangs of youthful tousle-haired skateboarders and pop-up artisanal food markets to admire also. And those daft living-statue things. They give me the creeps.

Of course, the BFI Southbank, formerly known as the National Film Theatre, is another neighbour. Pop in here to watch a film, visit the library, browse the museum displays, shop in the filmstore (DVDs, books, magazines, T-shirts) or just lounge in one of the trendy cafés with a cappuccino. If you’re wearing the film-buff uniform of black polo neck and chunky glasses while carrying a copy of Film as Art, you’ll fit right in.

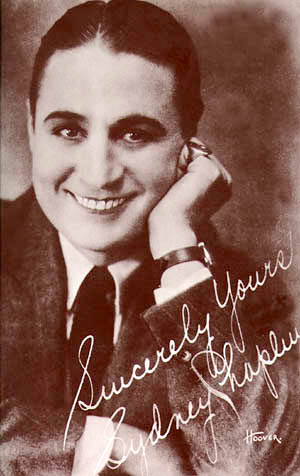

The best thing about the Southbank for many film fans is that it’s a stone’s throw from where a little-known film-maker called Charlie Chaplin grew up. Feel the vibe, take a detour into Lambeth, commune with his spirit, and if you are feeling flush, take a trip to the London Film Museum further down the river where you can browse their permanent exhibition on the Great Londoner.

2. Tickets

Happily, seats for Napoléon start at a very affordable £11, but they do go up to £60 for a “premium experience”, which may tempt you to push the boat out. Tickets are available here, and you’ll be able to pick and choose where you want to sit. For more information, especially if you have not been to the RFH before, try the very useful website TheatreMonkey, which will explain where the best (and worst) bargains are to be had.

3. Practicalities

You’ll probably need somewhere to stay: Napoléon begins at 1.30pm and doesn’t finish until 9.30pm, which means you can probably get a late train home, but you’ll more than likely be a bit dazed and in need of a liedown. London is one of the most expensive cities in the world, which means that hotels are not cheap, I’m afraid. So, if your budget doesn’t stretch to the Ritz or the Savoy, check out one of the economical chains such as Travelodge, Premier Inn or Holiday Inn; book in advance and look for a location that is handy for public transport rather than dead central. If you’re watching the pennies, commuting in as a tourist from Zone 3 or 4 of the tube network really doesn’t take very long and needn’t be stressful in off-peak hours. Cast your eyes eastwards, where hotels that sprang up in time for the London 2012 Olympics may be looking to fill up their empty rooms. Alternatively try the YHA, or Couchsurfing. You know about lastminute.com too, right?

You’ll want to eat before Napoléon, during Napoléon, or after Napoléon. Possibly all three. There is a 100-minute interval for a reason and a person can’t live on coffee and cinematography alone. Not a problem though. There are cafés and bars in the Southbank Centre, and quite-posh restaurant called Canteen too (book ahead). There’s also a pizza place opposite and all kinds of food from sandwiches to noodles to burgers available nearby on the Southbank. The RFH itself is licensed too, if you want to accompany your viewing of a French cinema classic with un petit vin rouge.

Some of the nearby bars will open late, if you want to party like it’s 1927 after the movie, and the tubes run until around 1am, with nightbuses and black cabs to scoop up the wilder ones among you.

4. Crime

We’ve all read Oliver Twist and learned that London is crammed with grubby-faced urchins with their eyes on your pocket watch. Sort of. Pickpocketing and other crime does happen, but not really as often as you may think. Keep hold of your valuables in crowds, think twice before walking home somewhere quiet late at night, and don’t jump into an unlicensed minicab. Just like you’d do at home.

5. Conversation

English innit. Just like what the Queen talks. But if you want to mingle with ease among the British silent film crew, just drop in a few references to “Porders”, the carrier-bag rustlers in NFT2, your intimate friendship with Kevin Brownlow, the LFF archive gala, that time you got lost on the way to the Cinema Museum/inside the Barbican, the latest issue of Sight & Sound, where you think next year’s BSFF should be held and, of course, your devotion to a certain marvellous silent cinema website, whose name briefly escapes me.

Seriously, this should be a very social occasion, and hopefully between this site, the Bristol Silents site, Nitrateville and the wider world of Twitter and Facebook, we should be able to make quite a party of it and meet lots of new and old faces. Don’t be a stranger.

6. Weather

Obviously, this is another popular topic of conversation. If you’ve not been to the UK before, you need to know that London in November will be cold. Not properly cold, not Norway cold, but definitely nippy. Bring your coat and your umbrella too, because the English skies love to rain. Unfortunately, however, you have been lied to by the movies and there is very little chance of you being caught in a “right old pea-souper”. That’s a good thing, really, as the views down the Thames from the Southbank are gorgeous.

7. Being a tourist

Apparently there is more to do in London than just watching old movies. News to me. If you’re staying for a few days, and you have exhausted all the possibilities here, then you’ll want to look further afield for entertainment. An official tourism website such as this one should keep you busy with palaces, museums, West End shows, abbeys and graveyards, but for something a little more quirky, cultural or off the beaten track, try the dispatches from Londonist or the listings from Time Out. The Vintage Guide to London may well be your cup of char too.

8. Preparation

Once you’ve read Kevin Brownlow’s wonderful book about the filming and restoration of Napoléon, and listened to a sampler CD of Carl Davis’s score you’ll want to watch Abel Gance’s earlier films J’Accuse and La Roue on DVD. This has a two-fold benefit: you’ll learn more about the great French impressionist’s work, and you will become accustomed to watching really, really long films too.

And to get you in the mood for the big show in November, anyone based closer to London should book now for Modern Times in March and The Thief of Bagdad in June – both Photoplay presentations with Carl Davis and the Philharmonia, just like Napoléon, and showing at RFH too.

9. Souvenirs

Your loved ones will no doubt be delighted that you went all the way to London just before Christmas and brought back lots of Region 2 DVDs from the BFI shop for their stockings. I can just imagine their happy faces now. On the off-chance that that isn’t true, London has lots more to offer shops-wise. Covent Garden, Camden Market, Marylebone High Street and the gift shop at any of the big museums should sort you out and keep your rellies happy. The London Transport Museum gift shop in Covent Garden is particularly good for retro souvenirs of Laaaahndan Town. Alternatively, you can buy some Edinburgh shortbread at the airport. No one will know the difference.

10. If, sadly, you can’t make it this time

Napoléon screens at the Royal Festival Hall on 30 November 2013, accompanied by the Philharmonia Orchestra.