Ready for the game tonight? Warm up with this treat from the BFI archives. England play Ireland at Manchester City’s Hyde Road ground on 14 October 1905. The film is only three minutes long, but don’t worry, I can reveal that England won the game 4-0!

Ten ‘firsts’ by Eadweard Muybridge

This is a guest post for Silent London by Robert Seidman, author of Moments Captured, a novel based loosely on the work and life of the pioneering 19th century photographer Eadweard MuybridgeThe Silents by Numbers strand celebrates some very personal top 10s by silent film enthusiasts and experts.

Nine Firsts – and One Disputed First – by Eadweard Muybridge, Photographer Extraordinaire

1. The Trotting Horse

In 1878 Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) created the mechanism that recorded the first photographs of a horse trotting. No photographer had ever been able to capture such rapid motion before. Muybridge’s multi-camera mechanism stopped time and seized motion itself so that he and his employer, California’s ex-governor Leland Stanford, could analyse the animal’s gait and improve the training of his racehorses.

2. The Photo Finish

Muybridge was at a racetrack when two horses finished in a dead heat. The usual volatile debate followed about which animal had triumphed. The dispute tripped Muybridge’s innovative impulse, and soon Eadweard invented the first device to record the “photo finish”. In a letter to Nature magazine in May 1882, Eadweard Muybridge argued that every horse race should make use of a high-speed photo at the finish to determine the winner. A camera very much like the one that Muybridge deployed still determines the outcome of contested horse races.

3. Photo Finish Ubiquity

The idea of Muybridge’s photo finish was later expanded to include other sporting events, including foot races and swimming contests. Today, on TV and in film, the grace and agility of divers and swimmers, sprinters and footballers are presented in stop-motion, yet another of Muybridge’s contributions to the way we see and perceive.

4. Panorama

In January 1877, Muybridge placed his view camera on the roof of railroad magnate Mark Hopkins’ half-finished mansion in the posh Nob Hill neighborhood of San Francisco and began the process that recorded the most detailed and complete – though not the first – panoramic view of the city. Starting at 11am and using the contemporary equivalent of a telephoto lens, Muybridge took 13 photos as he carefully moved his camera around in 360 degree circle. The panorama remains the most complete description of the City’s “Golden Era” before its partial destruction in 1906 by an earthquake and subsequent fire.

5. The American West and US National Parks

Throughout the late 1860s Muybridge produced a stunning portfolio of the wild beauties of the American West, including breathtaking documentation of Yosemite before it became a national park. Multiple historians assert that the photos helped spur the National Parks movement itself. Theodore Roosevelt, the father of the US National Parks system, was directly influenced by Muybridge’s and other early photographers views of the American wilds.

Dodge Brothers and Neil Brand bring silent cinema to Glastonbury for the first time

On Saturday night at Glastonbury 2014, the mud, the terrible noodles and the hangovers will all be worth it. For the first time ever, a silent film will play the country’s leading rock festival. Neil Brand and the Dodge Brothers will perform their rousing score for William’s Wellman’s rail-riding rollercoaster Beggars of Life in the Pilton Palais cinema tent, at 6pm on 28 June. We’ll be there – will you?

Hollywood Before Glamour: Fashion in American Silent Film – review

“To the feminine mind nothing appeals quite as strongly as clothing, hats, or shoes – in fact finery of any kind,” opined Moving Picture World in 1916. Gentlemen spectators apparently preferred films with fighting in them. On finishing this fascinating survey of how the fashion and film industries met and grew together in the early 20th century, I’m inclined to excuse MPW’s sweeping generalisation.

Clothing, and fashion, are at the heart of everything that Hollywood has ever done. All film is spectacle, early film unambiguously so – and nothing epitomises the excesses of La-La Land more than the view of preening, primped movie stars lining up on the red carpet draped in borrowed couture and jewels. Baffling then, to remember that the first film actors were required to supply their own costumes. Turning up well-dressed to an studio (as the supremely stylish teenage Gloria Swanson did at Essanay) could secure you a chance at stardom. Even when studios had appointed a seamstress, numbers were so short that they would frequently be called upon to play roles on screen. In fact, Hollywood wardrobe departments would be staffed by many a former actress. And because few people kept proper records of who did what in the early studios, it is the memories of stars such as Swanson and Lillian Gish that often provide the clearest picture of how the costumes were supplied, chosen and recycled in-house.

To begin with, Michelle Tolini Finamore’s scholarly illustrated book examines fashion trends that made for great movie subject matter, from the exploited women working in sweatshops that churned out shirtwaists for America’s increasingly well-dressed urban working-class, to the extravagant picture hats that caused havoc in Nickelodeons, to the risque Paris styles that marked a lady out as a vamp. The idea that US fashions were practical and democratic and French ones outlandish and revealing kicks off a major theme in this book – the battle for fashion supremacy between first New York then LA with Paris.

Continue reading Hollywood Before Glamour: Fashion in American Silent Film – review

An exclusive interview with @MsLillianGish

Don’t believe everything you read in the press. Contrary to published reports, legendary silent film actor Lillian Gish is not dead – she’s alive and well and totally winning at Twitter. Using the handle @MsLillianGish, the star of Broken Blossoms and The Birth of a Nation drops wisdom on the internet from a great height every day. Check out her Twitter biography, which is typically witty, informative and self-effacing: “I am the greatest actress of all time. If I had been a scientologist, you all would be one today. Yeah, I rocked it like that.”

Not content with enjoying Ms Gish’s wise words 140 characters at a time, I asked the star if she would be happy to answer a few questions for the benefit of the Silent London readers. To my great delight, she accepted. Unfortunately the time difference did not allow us to conduct the interview live, but I posted some questions to Ms Gish, and with her help of her loyal secretary she was able to answer them. Her responses are illuminating, I think you’ll agree. Here is the transcript of my interview with Lillian Gish …

A modern city symphony for London – and how you could get involved

This beautiful short, Hungerford: Symphony of a London Bridge, is a mini city symphony directed by Alex Barrett in 2010. It has won several awards, appeared at many festivals, and here at Silent London we have long admired it. Barrett, a writer, film-maker and regular Silent London contributor, has a more ambitious project in the works, though: London Symphony, a feature-length silent film about our fair capital. Barrett is a huge admirer of European silent cinema, and the city symphonies of the 1920s avant-garde. He plans to start shooting London Symphony later this year. Here’s how he describes the project:

London Symphony is a poetic journey through the city of London, exploring its vast diversity of culture and religion via its various modes of transportation. It is both a cultural snapshot and a creative record of London as it stands today. The point is not only to immortalise the city, but also to celebrate its community and diversity.

He’ll be asking for your help though – Barrett and his team want to crowdfund their movie, and you’ll be hearing more about that in the summer on these very pages.

For now, the best way to follow the progress of London Symphony is to sign up to the mailing list here . You can also follow London Symphony on Twitter @LondonSymphFilm and Facebook too.

Toronto Silent Film Festival 2014: talking about intertitles

It was a great honour for me to be asked to speak on the opening night of the Toronto silent film festival recently. It’s just a pity that geography was against us. But the speech was recorded ahead of time, and looked very smart, thanks to a colleague in the multimedia department at the Guardian generously helping me out – Andy Gallagher shot, produced, edited and did absolutely everything except sit on that blue chair.

You will probably be able to spot that it’s my first stab at presenting something like this, but it’s on the topic of silent film intertitles, which I am very enthusiastic about – the too-often unsung heroes of silent cinema. I hope you enjoy it.

Wonderful London 1924 & 2014

Film-maker Simon Smith has made another silent cinema mashup to delight any Londoner. His previous film spliced scenes from Friese-Greene’s The Open Road (1927) with the same London streets filmed in 2013. The new clip embeds scenes from the Wonderful London actuality into vistas of the capital in 2014. The effect is stunning – it’s fascinating to compare London as it is and as it was, and as the 1920s city-dwellers step out of their fuzzy sepia frames they become ghosts haunting our 21st-century streets.

As much as London has been rebuilt and redeveloped over the past century, this clip reminds us that its past has not been erased, just sunk below the surface.

Five silent films to avoid … and five to seek out

This is a guest post for Silent London by John Sweeney. John Sweeney is one of London’s favourite accompanists, composing and playing for silent film and accompanying ballet and contemporary classes. He researched and compiled the music for the Phono Cinéma-Théatre project and is one of the brains behind the wonderful fortnightly Kennington Bioscope at the Cinema Museum. The Silents by Numbers strand celebrates some very personal top 10s by silent film enthusiasts and experts. When Silent London started with these lists I joked with a friend that what was needed was a list of silent films to avoid: no sooner had I spoken than films started coming to mind, but I also started thinking of the opposite list, of films that aren’t anything like as well known as I think they should be. So, I’ve settled for five films that you might think would be good but really aren’t, and five films that are definitely worth seeking out. Opinions differ and it’s quite possible that I’ve missed the point of some the films – put me right in the comment space below if you disagree.

This is a guest post for Silent London by John Sweeney. John Sweeney is one of London’s favourite accompanists, composing and playing for silent film and accompanying ballet and contemporary classes. He researched and compiled the music for the Phono Cinéma-Théatre project and is one of the brains behind the wonderful fortnightly Kennington Bioscope at the Cinema Museum. The Silents by Numbers strand celebrates some very personal top 10s by silent film enthusiasts and experts. When Silent London started with these lists I joked with a friend that what was needed was a list of silent films to avoid: no sooner had I spoken than films started coming to mind, but I also started thinking of the opposite list, of films that aren’t anything like as well known as I think they should be. So, I’ve settled for five films that you might think would be good but really aren’t, and five films that are definitely worth seeking out. Opinions differ and it’s quite possible that I’ve missed the point of some the films – put me right in the comment space below if you disagree.

Five silent films to avoid

Note: I make no claim that these are the worst films – merely that they should be a lot better given their reputation, or who made them.

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1916, Stuart Paton)

Yes, this film features groundbreaking underwater photography for a few minutes, but the screenplay is stupid, the acting is ridiculous, and the editing’s completely random. On IMDB someone writes “It’s by no means a bad movie”, but it is, it really is! Do not watch this movie.

- If it’s submarines that float your boat, try Submarine, directed by Frank Capra.

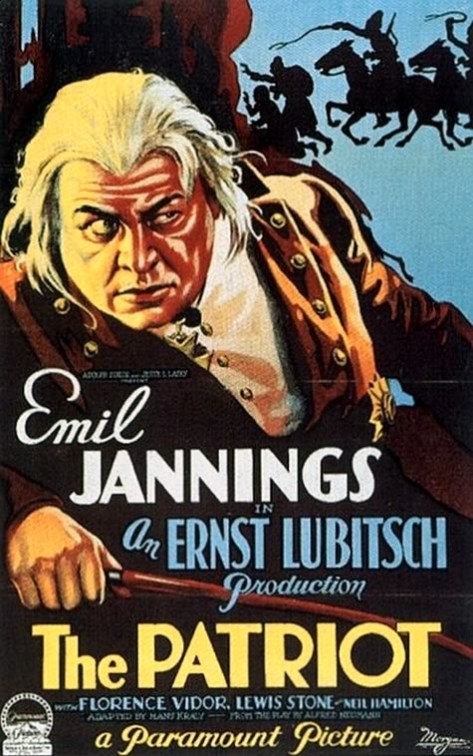

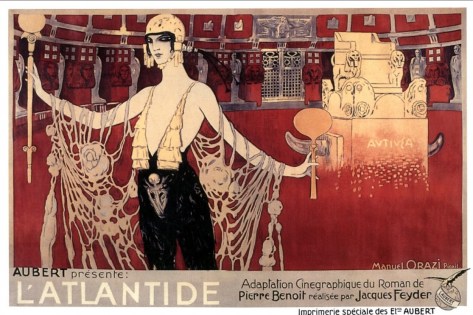

L’Atlantide (1921, Jacques Feyder)

Jacques Feyder was a wonderful director, as anyone who’s seen his Visages d’enfants will know, but this exotic farrago, weighing in at almost three hours, is dreadful. Two French soldiers stumble on the lost kingdom of Atlantis, in the middle of the Sahara Desert (!), which is ruled by the ageless Queen Antinéa. Featuring far too much sand and a decidedly uncharismatic performance from Stacia Napierkowska as the supposedly endlessly fascinating and desirable queen, you really don’t need to see this film.

- Watch instead: Visages d’Enfants.

Continue reading Five silent films to avoid … and five to seek out

Sunday night is watch-a-silent-film-that-isn’t-The-Artist-night

The Silent London social media accounts are here to help, so on Thursday evening, I passed on the news that The Artist is screening on BBC2 on Sunday night.

Immediately some people reacted with horror. I quite liked The Artist. OK, up to a point. But some people really didn’t!

Lucie Dutton came up with this neat suggestion

https://twitter.com/MissElvey/status/459423641441402880

Which gave me an idea.

How about it guys? I’m assuming you’ve seen The Artist, you don’t want to see it, or you can set the tape for it*. So why not nominate Sunday night silent movie night. Stick on a film, and tell me what you’re watching here in the comments or on Facebook or Twitter, using the hashtag #silentfilmthatsnottheartist. It’s the perfect excuse to enjoy a silent, and chat to your friends at the same time. And isn’t that half the point of these modern silents? To revive our passion for the real deal?

Not sure what I will be watching, but it may well be something British, or first-world-war-ish. How about you? Are you in?

*Program your hard-disk recorder, natch

Studying Early and Silent Cinema by Keith Withall: review

I watched my first silent films, not on my grandpa’s knee, nor at one of these grand screenings with live music that they have nowadays, but in a sixth-form college classroom while being guided through my film studies A-level. It’s not a very romantic story, but I loved what I saw, and while studying for my exams, and subsequently at university, I sought out, saw, and enjoyed many more silents – going from a teenage film fan to an early cinema buff-in-waiting. The film studies syllabus (WJEC, a few years ago now) that I took was great – introducing us to relatively obscure arty silents as well as a healthy appreciation of Hollywood industry mechanics and even a smattering of theory. It stood me in good stead for my English lit & lang degree and a master’s in film history. Plus, I doubt the 18-year-old me would ever have got to see Un Chien Andalou without it. If you want someone to take the blame for Silent London, you can point your finger squarely at a tertiary college in Ealing W5. (I chose the college, incidentally, primarily because it was so close to the famous film studios.)

The point is, I think that sixth form is a great time to introduce people to early and silent film. Teenagers who seek out noisy bands and edgy art want off-beat films to watch too. Silents fit the bill perfectly. There’s something off-kilter about silent movies when you first meet them, and something unexpected about a supposedly modern subject area taking you so far back into the past.

Cheering then, to see Keith Withall’s Studying Early and Silent Cinema land on my desk. It’s an expansion of a 2007 volume and clearly informed by two things: his years spent teaching film studies at FE and HE level, and a passion for attending the film festivals at Pordenone and Bologna. This is a useful work for anyone interested in silent cinema to use as a reference but a great introduction to the subject for students. It’s a read-this-now-watch-that thing, and I’m all for it. Not only that, but Withall blogs too, posting thoughtful, erudite essays at cinetext.wordpress.com

Withall’s expanded book is an enjoyable and wide-ranging introduction to the key concepts and landmarks in the early and silent film period. This guide tackles a breathtakingly vast amount of material in the clearest of terms, and always with one eye on the here-and-now. There are references not just to modern films and attitudes, but also practical consideration of the availability of viewing material. Case studies examine classic films in detail, while wider sweeps take in potted histories of alternative and smaller national cinemas. Throughout, Withall encourages students towards wider exploration of the subject area – and most importantly, towards further viewing.

Studying Early and Silent Cinema by Keith Withall will be on sale in May 2014, priced £16.99 in paperback (ISBN: 978-1-906733-69-8) and £50 in hardback (ISBN: 978-1-906733-70-4), published by Auteur

Studying Early and Silent Cinema by Keith Withall will be on sale in May 2014, priced £16.99 in paperback (ISBN: 978-1-906733-69-8) and £50 in hardback (ISBN: 978-1-906733-70-4), published by Auteur

Lillian Gish and The Wind: ‘It excited my imagination’

The Wind screens with a specially commissioned live musical accompaniment from Lola Perrin at the Electric Cinema, London, on 9 April 2014, and the Watershed Cinema, Bristol, on 30 April 2014

This is a guest post for Silent London by Kelly Robinson. If you haven’t seen The Wind, be warned that this article discusses the ending of the film.

Ethereal, delicate, poetic, otherworldly are just some of the somewhat elusive adjectives used to describe Lillian Gish since the early years of her stardom. Effusive admirer Vachel Lindsay said “Lillian Gish could be given wings and a wand if she only had directors and scenario writers who believed in fairies.” However, in reality Gish had her feet firmly on the ground. She had a career spanning eight decades, was a spokeswoman for cinema’s history with high artistic ambitions for herself and for the medium. King Vidor, who directed her in La Boheme (1926) commented: “The movies have never known a more dedicated artist than Lillian Gish.”

In his autobiography A Tree is a Tree Vidor said that Gish was incredibly assertive and had her own thoughts about the filmmaking process. Indeed, she knew a great deal about cinematography and in particular lighting. She had learned her trade during the more collaborative process of the silent era, where she had received extensive tutelage from DW Griffith in a production context where actors frequently worked without scripts and where they were encouraged to collaborate on characterisation and staging. She may only have had had a small acting role in Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), however she designed and furnished sets, helped with lighting and cutting, wrote intertitles and advertising copy.

Continue reading Lillian Gish and The Wind: ‘It excited my imagination’

Shaun the Sheep the Movie: teaser trailer – video

Will this be something we consider to be a truly silent film? Who knows. But it’s dialogue-free, delightful and comes to us courtesy of our friends at Aardman Animations, whose support for the Slapstick Festival is legendary. Shaun the Sheep the Movie is scheduled for release in spring 2015. Not just for kiddywinks, we’re sure.

More details here – and on the official Shaun the Sheep website.

From Aardman, the creators of Wallace & Gromit and Chicken Run, comes the highly anticipated big screen debut of Shaun the Sheep. When Shaun decides to take the day off and have some fun, he gets a little more action than he baa-rgained for! Shaun’s mischief accidentally causes the Farmer to be taken away from the farm, so it’s up to Shaun and the flock to travel to the Big City to rescue him. Will Shaun find the Farmer in the strange and unfamiliar world of the City before he’s lost forever? Join Shaun and the flock on their hilarious, action-packed adventure in Shaun the Sheep the Movie – only in cinemas Spring 2015.

Lost Betty Balfour film discovered by EYE: Love, Life and Laughter (1923)

Genuinely exciting news for silent film fans. A long-thought-lost film starring the wonderful Betty Balfour, and directed by the somewhat elusive George Pearson, has been returned to us. The film is Love, Life and Laughter (1923): Betty “Queen of Happiness” Balfour stars in a typically winning role as Tip Toes, an impoverished chorus girl who dreams of fame on the music-hall stage. She befriends a young aspiring writer, also down on his luck, and they decide on a plan – to meet two years later back at their tenement building to see if either of them have achieved their fondest wishes.

Love, Life and Laughter was found in a cinema in Hattem, in the Netherlands. The cinema was due to be rebuilt and so the anonymous film cans stored there were taken to EYE, the the Dutch Film Museum, in the hope that they might contain footage of local historical interest.

The BFI’s curator of silent film, Bryony Dixon, welcomes the discovery with open arms, saying:

Contemporary reviewers and audiences considered Love, Life and Laughter to be one of the finest creations of British cinema, it will be thrilling to find out if they’re right! We hope to be able to acquire some material from our colleagues at EYE soon so that British audiences can have a chance to see this exciting discovery.

We know that the copy EYE has acquired of Love, Life and Laughter has Dutch intertitles and has the original tints and tones intact – and we do have reason to believe that it is a very special picture. Contemporary reviews praised the film, with the Telegraph saying it was “destined in all probability to take its place among the screen classics”. In the Manchester Guardian, CA Lejeune’s gives nicely rounded sense of the film, and its importance:

Love, Life and Laughter is the latest Pearson film, and legend has it that the latest Pearson film is aways the best. It is certainly the most ambitious, spectacular at times in the De Mille ballroom manner, lit and photographed with a beauty to dream of. Devotees have called it George Pearson’s masterpiece, and so it is – of bluff. He lights common things uncommonly, and legend makes them symbolic; he catches a series of farcical situations, and legend makes them comic; legend turns sentimentality into sentiment, and confusion into mystery.

This fantasy of a chorus girl and a young poet is clever, but chiefly clever in simulating cleverness, in tickling the intellectual vanity of its audience with a goose feather, coloured peacock by imagination. It will succeed. And its success will be the result not of innate quality but of the great Welsh-Pearson legend – and, when all is said and done, nothing else matters.

That rather guarded review takes on a new aspect when we remember that the “great Welsh-Pearson legend” has now been forgotten, and their films have almost entirely vanished – which has the affect of rather enhancing the title’s allure. Until its rediscovery, Love, Life and Laughter sat on the BFI’s 75 Most Wanted list of much-missed British films.

A 1923 programme for the film offers this romantic and tantalising description:

“The Story is but a simple exposition of the oldest, yet ever youngest desire of the human heart, the achievement of an earnest ambition. The incidents tell in picture form of the striving of a boy and girl, against the odds of the world. The portrayal of this struggle towards a final goal of the desired happiness is unconventional in treatment. The Boy and Girl laugh and weep, succeed and fail, move onward and forward to an inevitable destiny, and to a climax which should live long in the memory.”

One of the many attractive elements to this news is that the film’s subject matter – of two starry-eyed types struggling to achieve their artistic ambitions – resonates against the life stories of the director and star both. Poignantly, in light of the fact that this film has been missing for so long, both Balfour and Pearson were highly acclaimed in the silent era and subsequently forgotten by most. It’s discoveries such as this, in fact, that make us appreciate anew how terrible the odds of survival for silent cinema are – with 75% of silents by the wayside, for each one we treasure there are three more we may never see.

Continue reading Lost Betty Balfour film discovered by EYE: Love, Life and Laughter (1923)

The Mordaunt Hall silent movie quiz

Why Change Your Wife?: Cecil B DeMille and the New Woman

Why Change Your Wife? screens with a live score by Niki King as part of the Birds Eye View Film Festival on 10 April 2014 at BFI Southbank, at 6.10pm

This is a guest post for Silent London by Kelly Robinson

Cecil B DeMille is perhaps predominantly remembered for his big-budgeted biblical epics of the 1940s and 50s. For instance, the captivatingly lurid Samson and Delilah and The Ten Commandments are both still television staples. However, DeMille had a career that spanned several decades and he made more than 50 films in the silent era alone. Many of these early titles were similarly lavish and sensationalist, whilst also seeking to exploit contemporary social concerns.

Jesse L Lasky, Vice President of Famous Players-Lasky (Paramount), encouraged “modern stuff with plenty of clothes, rich sets, and action”. Savvy to the growing female audience, Lasky contracted screenwriter Jeanie Macpherson to portray women “in the sort of role that the feminists in the country are now interested in … the kind of girl that dominates … who jumps in and does a man’s work.” The result was several delightful, enormously successful, marital comedies, starting with Old Wives for New and followed by Don’t Change Your Husband. Why Change Your Wife? completes the “does what it says on the tin” trilogy. With their focus on female glamour and desire, these films offer more permutations of the “New Woman”, which Birds Eye View has explored in previous Sound & Silents strands.

Considering his somewhat indomitable, patriarchal image, it is perhaps surprising to find a large number of women amongst Demille’s regular collaborators. Anne Bauchens edited his films, from Carmen (1915) all the way through to The Ten Commandments (1959), his last film. In his unpublished autobiography he wrote that it was an essential clause in every contract that she be his editor. In the Los Angeles Herald Examiner he is quoted as saying that: “‘though a gentle person, professionally she is as firm as a stone wall … We argue over virtually every picture.”

Continue reading Why Change Your Wife?: Cecil B DeMille and the New Woman

Quiz: Are you a silent film geek?

At Silent London, we like to offer a warm and cuddly welcome to all silent film enthusiasts, from novices to nerds. But which are you?

This quiz is just a bit of fun … but do report back in the comments if you are delighted or outraged by the results.

And of course, if you feel the need to brush up your geekiness – sample a screening or two on the Silent London calendar.

Ten lost silent films

This is a guest post for Silent London by David Cairns, a film-maker and lecturer based in Edinburgh who writes the fantastic Shadowplay blog. The Silents by Numbers strand celebrates some very personal top 10s by silent film enthusiasts and experts.

British Silent Film Festival: 2014 style

Just like last year, the British Silent Film Festival hits London town, but not in its traditional form. Very much as was the the case last year, actually, the festival proceeds in a slightly cut-down version, comprising a symposium at Kings College London on Friday 2 May 2014 and a full day of screenings at the Cinema Museum on the next day.

There’s a loose theme to those screenings at the Cinema Museum – runaway women or some such. I like. More to point: Betty Balfour fans – fill your boots. And if you want to submit a proposal for a paper to the symposium, you have until 31 March – so hurry up, clever clogses.

Here are the full details for each day:

The British Silent Film Festival Symposium 2014 will take place on 2nd May 2014 at King’s College, London.

Following the success of last year’s symposium, this one-day event again seeks to draw together scholars and enthusiasts of early British cinema, and operate as a forum for the presentation of new research, scholarship and archival work into film culture in Britain and its Empire before 1930. Possible areas may include but will not be confined to: Cinema in the context of wider theatrical, literary and popular culture; Empire and cinema; Cinema and the First World War.

An early evening screening of The Wonderful Story (Graham Cutts, 1922) will be included in the day’s events.

Proposals (around 200 words in length) are invited for 20 minute papers on any aspect of new research into film-making and cinema-going in Britain and its Empire before 1930. Please submit them to Lawrence.1.Napper@kcl.ac.uk by 31st March.

Read more on Facebook & register for the symposium here

Put-upon ladies take on the world in this programme of rarely seen silents from the BFI National Archive.

A double bill from talented Hungarian director Geza von Bolvary, stars Britain’s favourite actress Betty Balfour as the stand-in princess in The Vagabond Queen (1929) and besotted bottle-washer in Bright Eyes (1929). Also yearning to break free, an oppressed wife hangs her hopes on a typewriter in J.M. Barrie’s The Twelve Pound Look (1920) and a programme of shorts continues the theme.

PROGRAMME

- 10.00-11.30 The Twelve Pound Look

- 11.30-12.00 Break

- 12.00-13.30 The Vagabond Queen

- 13.30-14.30 Lunch

- 14.30-16.00 Shorts programme

- 16.30-18.00 Champagner/Bright Eyes

Doors open at 09.00 for a 10.00 start.

Refreshments will be available in our licensed café/bar.

TICKETS & PRICING

£25 for the full day, £15 for a half day, £8 for one session. Sorry, no concessions.

Advance tickets may be purchased from WeGotTickets, or direct from the Museum by calling 020 7840 2200 in office hours.

UPDATE: tickets on sale now

Read more on the Cinema Museum website

Hippodrome Festival of Silent Cinema 2014: reporting back

Silent London podcast: Hippodrome Festival of Silent Cinema 2014

I’ve just returned from the Hippodrome Festival of Silent Cinema in Bo’ness, Falkirk. It’s a fantastic event – I really enjoyed myself and only wish I could stay longer. To give you a flavour of the weekend, if you missed out this time, here’s a mini-podcast and a selection of social media updates too. Surely there is no cooler hashtag for a #silentfilm event than #hippfest?

Hats off to Alison Strauss and her team and Falkirk Community Trust to – Hippfest is a triumph.

UPDATE: Here’s my Hippfest report for the Guardian film blog

Continue reading Hippodrome Festival of Silent Cinema 2014: reporting back