If you attend the occasional silent movie screening, like I do, you’ll have experienced a particular bittersweet feeling. As much as you enjoyed the show, you fear you could never quite recreate the magic. You know the film is out there waiting for you to watch again (somehow), but nine times out of 10, the improvised music that accompanied it lives only in the corner of your memory.

The genius of improvisation is that the melodies, or that special combination of them, are conjured out of thin air, and disappear just as fast. Unless … someone, say Neil Brand, were to sit down at the piano and record some of those tunes for posterity.

So that is exactly what Brand has done – he has released an album of some of his favourite tunes to accompany classic silent films (from Pandora’s Box to Safety Last!). It’s a pleasure to listen to, and an enjoyably infuriating silent movie quiz too: the sleeve notes will tell you which film each track belongs to: can you guess without looking, and for an extra 10 points, can you pinpoint the scenes that inspired each excerpt?

Over to Brand’s notes to explain further:

In this album I have tried, for the first time, to give my improvised silent movie accompaniments a little life of their own away from the films, as piano pieces. They carry the essence of my musical thoughts on what these films are about, but you can listen to them without knowing the films, and let the pieces create your own pictures in your head.

Those sleeve notes also include a short intro by Brand to each film. So if you like what you hear, and you haven’t yet encountered the movie in question … well you couldn’t really ask for a better introduction.

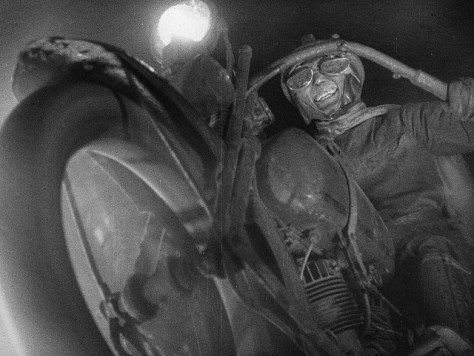

I’ve had a listen to the album, and it really is wonderful. What I didn’t expect, was to feel the same shivers down my spine that I would experience when watching Louise Brooks dance, or Murnau’s camera swooping through the morning mist. This is the most evocative of music – I felt that I was in the film as much as viewing it, whirling through the streets of Berlin (People on Sunday), Charlestoning with Clara Bow (It), marching in step with John Gilbert (The Big Parade) and dangling precariously with Harold Lloyd (Safety Last!).

Continue reading Review and competition – Neil Brand’s Out of the Dark: Silent Movie Themes