This is a guest post by Henry K Miller for Silent London. Henry K Miller is the editor of The Essential Raymond Durgnat (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). He is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound and has taught film at the University of Cambridge.

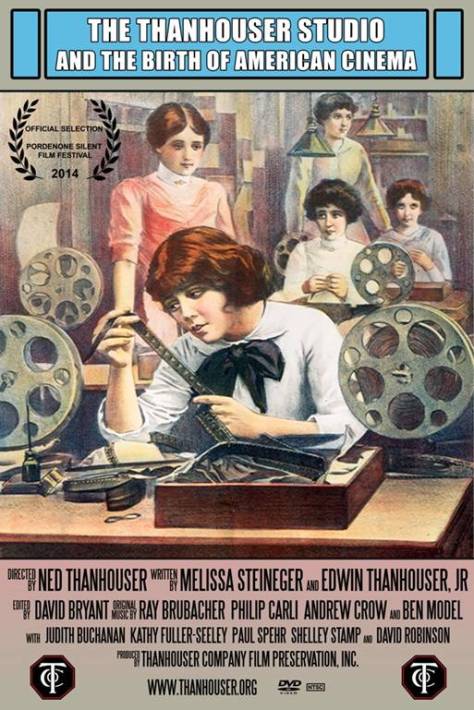

Though it was built by the grandest American film corporation, Famous Players-Lasky, no contemporary report of the film studio on the Regent’s Canal ever confused Shoreditch with Southern California. All were in agreement over its incongruous location, noting the contrast of imported glamour and native poverty – unscrubbed children, the smell of fried fish. There was less agreement, however, on what to call it, at least in the 1920s: sometimes “the Lasky studios”, sometimes “Islington” (the local telephone exchange was Clerkenwell; Hoxton is also arguable), often “Poole Street”. “Gainsborough” seems to have stuck only later, probably because of the famous Gainsborough melodramas, made towards the end of the studio’s life in the 1940s. Uncertain nomenclature notwithstanding, Gary Chapman is right to describe his subject as “a microcosm of the evolution of the British film industry during the silent era”.

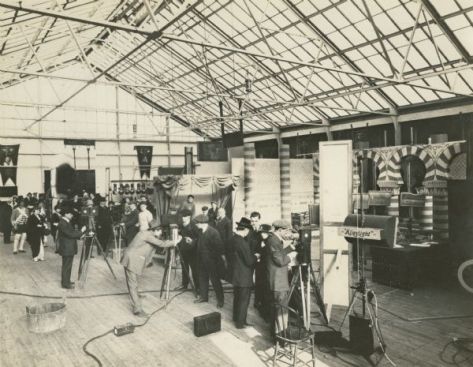

FP-L established itself in what had been a power station soon after the Great War, apparently in order to exploit European locations and West End playwrights, and sent over some of its most talented staff; but the first films to emerge from N1 were poorly received, and by the time the reviews began to improve the plug had been pulled. Most of the Americans departed by the middle of 1922. They left behind the best-equipped studio in Britain – early difficulties with the London fog having been overcome – but its survival as a rental facility was not guaranteed. The practices of “blind” and “block” booking – mastered by Famous Players-Lasky itself – made it very difficult for British filmmakers to get a look-in, even in British cinemas, and production was in the middle of a five-year slump. As Chapman shows, the producers who took on the Islington studio in 1922–3 were the bravest of a new breed.

Continue reading London’s Hollywood: The Gainsborough Studio in the Silent Years – review