This is a guest post for Silent London by Duncan Carson, a film event producer who organises the Nobody Ordered Wolves screenings. You can follow Duncan on Twitter at @nowolvesplease

This is a guest post for Silent London by Duncan Carson, a film event producer who organises the Nobody Ordered Wolves screenings. You can follow Duncan on Twitter at @nowolvesplease

This is a guest post for Silent London by Peter Baran. You can follow Peter on Twitter at @pb14.

Frau Im Mond is one of the first silent movies I saw as an adult. And despite its audacious special effects I can honestly say Fritz Lang’s rocket opera was not my gateway drug to silent film. Instead I saw it to justify the décor of my recently redecorated flat. I wanted to hang an attractive film poster above my stairs; for quite some time it was going to be Metropolis, until I saw the poster for Frau Im Mond, and its iconic rocket. As a science-fiction fan, and a film buff, how could I resist this picture? However, it seemed like cheating to have a poster of a film I hadn’t seen hanging above my stairs. So that is why I saw Frau Im Mond six years ago, having bought the previous Masters Of Cinema DVD release.

Now it is back, re-released in dual format Blu-ray and DVD, and seven minutes of additional footage have been added to the film, which brings the running time up to a handsome two hours and 49 minutes. As with the recently reconstituted Metropolis, Lang takes his time but doesn’t waste a minute. It is just that for much of the film each minute could have been thirty seconds shorter, and the plotting gets in the way of what the film promises. While Frau Im Mond is a notable film in both Lang’s filmography and in the history of science-fiction cinema, it is also way too long and ponderous – considering its wonderful potential.

Written by Fritz Lang’s wife Thea Von Harbou, and based on her novel of the same name, Frau Im Mond is one part conspiracy thriller and one part science-fiction tale. And that almost equally splits the running time, with the first hour and 20 minutes being a convoluted runaround between a professor, venture capitalists, enemy agents, a fiancée and a sparky kid. The rocket from the poster – and the justification for this being the first “scientific” science-fiction film – finally appears at one hour 18 minutes and the film does pick up considerably at that point, if only to give us some effects and even better Aran jumpers.

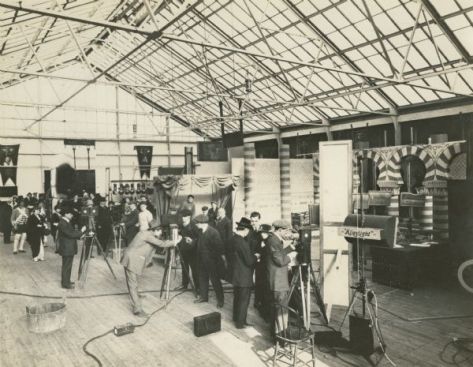

The story of the Thanhouser Film Studio follows a rise-and-fall pattern familiar to all aficionados of early cinema: innovation, success, expansion, loss, obscurity. But there is a gratifying twist in the Thanhouser tale that marks it out among its fellows.

Edwin and Gertrude founded the studio in 1909 in New Rochelle, New York as an independent outfit. They were successful for many years and made more than 1,000 films, shown all over the world, including some truly fantastic early literary adaptations. The biggest star on their books was probably the wonderful Florence LaBadie, heroine of the serial Million Dollar Mystery. You may also be familiar with the precociously winsome Marie Eline, AKA “The Thanhouser Kid”. Sadly, after many profitable years, in 1917, the downturn in the movie industry forced Edwin Thanhouser to close the company for good.

The story would end there, with Thanhouser another footnote in film history, were it not for the tireless efforts of Edwin and Gertrude’s grandson. Ned Thanhouser has spent the past three decades hunting down the movies that his grandparents made, as well as preserving and exhibiting them all over the world. Two-hundred-odd films later, Thanhouser is a name to conjure with, and the world is lot wiser about early American film-making. Just last year, a screening of Thanhouser films played to an appreciative crowd in London at the BFI Southbank.

But Ned has been working on another film project: a documentary about the family business.

This 50-minute documentary reconstructs the relatively unknown story of the studio and its founders, technicians, and stars as they entered the nascent motion picture industry to compete with Thomas Edison and the companies aligned with his Motion Pictures Patents Corporation (MPPC). Ned Thanhouser, grandson of studio founders Edwin and Gertrude Thanhouser, narrates this compelling tale, recounting a saga of bold entrepreneurship, financial successes, cinematic innovations, tragic events, launching of Hollywood careers, and the transition of the movie industry from the East Coast to the West and Hollywood. It will be of interest to scholars, archivists, early film historians, and everyone who loves the intriguing stories about the people who pioneered independent movie-making in America.

The Thanhouser Studio and the Birth of American Cinema had a little help over the finishing line from an Indiegogo crowdfunding campaign and it will be released next year. Excitingly for those of us Pordenone-bound in October, the film will have its premiere at this year’s Giornate del Cinema Muto. I’ll be there, will you?

Read more about studio, and the documentary on the Thanhouser site.

Name: The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands (1927).

Age: 87 years old. The clue’s in the number in brackets.

Appearance: Shiny and new.

Sorry, that doesn’t make sense – I thought you said it was 87 years old. The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands may be knocking on a bit, but it has been lovingly restored by the BFI and from what we gather, it’s looking pretty damn sharp. Just take a look at these stills.

Great, where can I see this beautiful old thing? At the Queen Elizabeth Hall on 16 October 2014 – it’s being shown at the London Film Festival as the Archive Gala. It will then be released in cinemas nationwide, and simultaneously on the BFIPlayer …

Blimey. And then it will be coming out on a BFI DVD.

Wonderful news, I’ll tell all my friends. Really?

No. I’ve never heard of it. Fair enough. You could have said that in the first place.

I was shy. Don’t worry, the BFI calls it a “virtually unknown film” on its website.

Phew. But you should have heard of the director, Walter Summers.

Rings a bell … He’s a Brit. Or he was, rather. And he was quite prolific, working in both the silent and sound eras. “I didn’t wait for inspiration,” he once said. “I was a workman, I worked on the story until it was finished. I had a time limit you see. We made picture after picture after picture.”

Continue reading London Film Festival Archive Gala: instant expert

This is a guest post for Silent London by Tony Fletcher, film historian at the Cinema Museum, about director-actor Alf Collins. Some of Collins’ Gaumont films will be shown on 30 August at a special open-air screening on the site of the original studio in Camberwell, with musical accompaniment by Neil Brand.

Alfred Bromhead started the English agency for Gaumont in Britain in 1898. He distributed the films produced by the French arm of the company, which was run by Leon Gaumont, and he also attempted to produce a few films in Britain in 1899. He opened a small outdoor studio on a four-acre cricket field in Loughborough Junction in south-east London. The open-air stage measured 30ft x 15ft However, this venture was short-lived and lasted for only one summer.

In 1902, Bromhead decided to make another attempt at producing films. Alfred Collins came on board as stage manager, and Gaumont continued producing short films over the next seven to eight years. These were often shot in the streets of south-east London – pioneering chase comedies and dramas. Alf Collins had already had some film experience working with Robert Paul, as well as at the British Biograph Company. He had started performing at the Surrey Theatre under George Conquest, later joining the William Terris Company at the Lyceum Theatre. He also performed in Drury Lane Pantos playing The Copper in the Harlequinade. His full-time job between 1902 and 1932 was as the stage manager for the Kate Carney Company, which gave him opportunities to make films when they were appearing in London and the provinces.

During 1904, Bromhead moved studios from Loughborough Junction to a 14-acre site at Freeman’s cricket field, Champion Hill. Thomas Freeman was a local builder and decorator living at 127 Grove Lane. In 1891, he had acquired a site at the rear of Champion Hill House and Oakfield House (roughly where Sainsbury’s superstore and Dulwich Hamlet FC are now situated). Freeman built three wood and iron cricket pavilions which were hired out during the summer to the Champion Hill Cricket and Lawn Tennis Club and during the winter to Dulwich Hamlet FC. These appear in some of the films. Bromhead constructed an open-air stage to film interior shots as no artificial lights were available.

Continue reading Alf Collins and Gaumont: south-east London’s cinematic past

Two years ago, Dziga Vertov’s landmark art film Man With a Movie Camera crashlanded into the top 10 of the Sight & Sound Greatest Films of All Time poll. Today, I can jubilantly announce that this year Movie Camera tops another Sight & Sound poll – the hunt for the Greatest Documentary of all time. There’s another silent in the top 10 too – the wondrous, beautiful, and controversial Nanook of the North (Robert Flaherty, 1922).

1. Man with a Movie Camera, dir. Dziga Vertov (USSR 1929)

2. Shoah, dir. Claude Lanzmann (France 1985)

3. Sans soleil, dir. Chris Marker (France 1982)

4. Night and Fog, dir. Alain Resnais (France 1955)

5. The Thin Blue Line, dir. Errol Morris (USA 1989)

6. Chronicle of a Summer, dir. Jean Rouch & Edgar Morin (France 1961)

7. Nanook of the North, dir. Robert Flaherty (USA 1922)

8. The Gleaners and I, dir. Agnès Varda (France 2000)

9. Dont Look Back, dir. D.A. Pennebaker (USA 1967)

10. Grey Gardens, dirs. Albert and David Maysles, Ellen Hovde and Muffie Meyer (USA 1975)

Both of these films deserve endless discussion and analysis, it’s true – as do the others in the list, from Shoah (Claude Lanzmann, 1985) to Don’t Look Back (DA Pennebaker, 1967), but I want to linger on Vertov’s film for now. I think it’s rather special – but I am intrigued by its success in this poll. For me Man With a Movie Camera is really an art film, not a documentary, because it foregrounds technique and display above truth-telling and information-imparting. Not that it doesn’t do that too, but in the world of documentary film-making, City Symphonies have every right to push form over content, and Man With a Movie Camera is the most invigorating of all City Symphonies. This is a movie about the sheer joy and madness of film-making – stopmotion, superimposition, freeze-frame, split-screens, rewinds, acute angles and all. It exalts in the possibilities of photography and motion. From the opening scene in which the cinema seats slam down one by one, onwards, we are sure that this will be a movie about the movies, and all the more enjoyable for that. It’s as addictive as popcorn, as edifying as high art.

Is it worthy of comment that Man With a Movie Camera is in the ascendancy at a time when there is little good news coming out of Ukraine? I’m not sure – for most viewers, I suspect this film is lumped in with the less-specific categories labelled “Soviet”, “Silent” and “Arthouse”. But it always does us good to remember that far-away parts of the world are synonymous with more than the bad news that hits the headlines. This poll result reminds us that Ukrainian cinema, as showcased at last year’s Pordenone Silent Film Festival, shines in our global film heritage. There are, you’ll note, no British films in the top 10.

Continue reading Man With a Movie Camera: the greatest documentary of all time?

Have you booked your fights yet? The 33rd edition of the world’s most prestigious silent film festival in Pordenone, Italy is looming – it will take place from 4-11 October, and tantalisingly, a few details have already been released. There are a few screenings already listed on the official website, and a shiny new press release (written in Italian) too. With the help of Google translate, let me tell you what I learned on the internet.

Alfred Hitchcock was born in the far east of London, in Leytonstone. So far east in fact, that it was Essex then, I think. But Hitch is still one of London’s most famous film directors, and it is fitting that one of his most famous films to be both set and filmed in the capital will be screening in his home borough of Waltham Forest this summer. The Barbican are showing the silent version of Blackmail, with Neil Brand’s tremendous score played by the Forest Philharmonic, at the Assembly Hall in Walthamstow, London E17. Be there or find yourself kicking your heels in a West End Lyon’s Corner House, rejected and alone.

Blackmail is a classic crime thriller, laden with Hitchcock’s signature suspense tricks, about a nice young girl (Anny Ondra) who commits a violent act one night in dire circumstances, and has to live with the consequences. Famously shot as both a silent and sound film, Blackmail reveals Hitchcock as a confident director revelling in the themes of murder and guilt that would become his home turf. In classic Hitchcock style, Blackmail also climaxes with a setpiece at a famous landmark – one slightly closer to home than Mount Rushmore. Every film fan in London should see this film, and the best way to see it is like this, with an orchestra and Brand’s wonderful music.

Continue reading Hitchcock’s coming home … Blackmail at the Walthamstow Assembly Hall

If you’re a Silent London reader, the chances are that you are already aware of the fantastic London Filmland blog, written by Chris O’Rourke. If not, there is still time to rectify that! O’Rourke researches cinemagoing in the capital in the silent era, specifically the 1910s and 20s. He publishes some fascinating snippets of what he has uncovered on the site, but I wanted to share this post with you in particular.

As part of the UCL Festival of the Arts this summer, O’Rourke led a walking tour of silent cinema venues around London and this video shows some of the locations he visited. There’s far more information on the original London Filmland post, of course, including a map of the tour. For those of us who regularly traipse along these same streets to see silent classics on the big screen, a trip to London Filmland shows us how it used to be done!

Join us at London’s famous Hideaway Jazz Club for our Buster Keaton Special! Some of Buster Keaton’s most well loved short films and a few surprises along the way … Live piano accompaniment by Tom Marlow, musician at The Lucky Dog Picturehouse (performed: BFI, Wilton’s Music Hall)We’ve got a fantastic offer of FILMS PLUS BUFFET just £13 (£10 concessions) next Thursday 24th July at the famous Hideaway Jazz Club, Streatham. Click here to buy tickets.

Advance Tickets include finger buffet from the Hideaway kitchen. Please arrive at 7.30pm for buffet (includes vegetarian selection).Please note: Tickets purchased after 21st of July will not include the buffet selection, but will be at the reduced price of £10. Food may be ordered separately at the venue.

But don’t forget – The Lucky Dog Picturehouse has two pairs of tickets to give away to Silent London readers. Just email your name to tldpicturehouse@hotmail.co.uk to enter the ballot. Here’s hoping you’re a lucky dog too!

This is a really fascinating idea, and a hugely entertaining hour and a half of anyone’s time. The BFI has compiled a typical “mixed” cinema programme from a century ago, and is releasing it theatrically this summer. It’s called, of course, A Night at the Cinema in 1914, and it comes out in August. Yes, you may be seated in an air-conditioned room with comfy seats and Dolby 5.1 sound, but you’ll be able to watch a variety bill of drama, actuality, comedy, serials and travelogues – just like your own great-grandparents in the Hippodromes of yore.

Some of the titles in the bill will be familiar to you, but there are a few surprises too – and the cumulative experience of watching 15 films in one sitting is wholly refreshing. There’s Chaplin, Florence Turner and Pimple larking about, but also newsreel footage from the front, and from suffragette demonstrations in London, and Ernest Shackleton’s preparations for his Antarctic voyage. Of course, there’s a segment from The Perils of Pauline, and an opportunity for a singalong too. Music is provided by an expert – Stephen Horne has recorded an improvised score for the whole shebang.

Continue reading A Night at the Cinema in 1914 – in August 2014

25 years after giving Un Chien Andalou a screaming chorus and a killer bass line to create Debaser, Black Francis of the Pixies has returned to silent cinema. While his latest endeavour is unlikely to rock your world in the same way that Doolittle did, there’s a little something here to entice fans of his jagged, surreal perspective. The Good Inn was written by Black Francis and Josh Frank, and its sublime illustrations are by Steven Appleby. A novel that occasionally borrows the form of a screenplay or a graphic novel, peppered with songs, intertitle cards and subtitles, this work is determined to be elusive. In the authors’ words, it’s “an illustrated novel, based on an in-the-works soundtrack, for a feature-length film that has yet to be made, about the first narrative pornographic movie ever made”. That all adds up to so much more than a mouthful, that it may well be a dog’s dinner.

With music, film history, cinema, and literature all vying for attention here, something had to give, and something has to shine. Hands-down, it’s the illustrations that carry the day here: Appleby’s diagrams, panoramas and visual gags elevate The Good Inn from messy indulgence to a book you may well want to treasure. As well as more conventional illustrations, Appbleby has provided annotated maps, visual gags, and charts to explain the passing of time, or the fallibility of memory. Without Appleby’s input, The Good Inn could be rather an ordeal.

This is a guest post for Silent London by Sabina Stent. You can read more of her reviews at silverembers.com

The name “Dr Caligari” may cause a shudder to those of a weaker disposition. The eponymous character of the 1920 classic Das Cabinets des Dr Caligari has long been a figure of terror – and with good reason. The film has been described not just as one of the first “horror” films, but one of the first examples of a movie generating a real psychological uneasiness in its audience. Caligari has been labelled in many different ways – German expressionism, horror story, psychological thriller and a classic of the silent era – but it was also Germany’s first postwar cinematic success, and it reflects the anguish of the people who had been through four terrible years.

Thanks to those classic expressionist touches, the sharp and angled sets, gothic imagery and expressionist undertones, Caligari was as visually frightening as its narrative. More recent audiences may have also been unsettle by the poor physical condition of prints of the film. Despite numerous attempts to finesse the quality of the film – first by the Filmmuseum München in 1980 and followed by the German Federal Film Archive (Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv) in Koblenz (1984) and as part of the Lumière European MEDIA project in 1995 – imperfections were still evident: visible scratches, jumps and blank screens, blurred title cards, unstable images and bleached-out, near-featureless faces.

Caligari’s story is told in partial flashback as Francis (Friedrich Fehér) tells the tale of the horrors that he and fiancée Jane (Lil Dagover) have endured at the hands of the Doctor. One day Francis and his friend Alan (Hans Heinrich von Twardowski) attend a local carnival where they watch the act of Dr Caligari (Werner Krauss) and the somnambulist Cesare (Conrad Veidt) “who has slept for 23 years but will tonight wake from his dream-like trance”. The only time Cesare speaks is to tell carnivalgoers their fortune. Cesare “knows the past and sees the future” and when Felix asks “how long will I live?” his serious, haunting response is: “To the break of dawn”. Yet the fear is not restricted to the carnival. At night Cesare is woken by Caligari to do his deathly bidding, and so begins a series of murders, abductions and mental unravelling.

Ready for the game tonight? Warm up with this treat from the BFI archives. England play Ireland at Manchester City’s Hyde Road ground on 14 October 1905. The film is only three minutes long, but don’t worry, I can reveal that England won the game 4-0!

This is a guest post for Silent London by Robert Seidman, author of Moments Captured, a novel based loosely on the work and life of the pioneering 19th century photographer Eadweard MuybridgeThe Silents by Numbers strand celebrates some very personal top 10s by silent film enthusiasts and experts.

1. The Trotting Horse

In 1878 Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) created the mechanism that recorded the first photographs of a horse trotting. No photographer had ever been able to capture such rapid motion before. Muybridge’s multi-camera mechanism stopped time and seized motion itself so that he and his employer, California’s ex-governor Leland Stanford, could analyse the animal’s gait and improve the training of his racehorses.

2. The Photo Finish

Muybridge was at a racetrack when two horses finished in a dead heat. The usual volatile debate followed about which animal had triumphed. The dispute tripped Muybridge’s innovative impulse, and soon Eadweard invented the first device to record the “photo finish”. In a letter to Nature magazine in May 1882, Eadweard Muybridge argued that every horse race should make use of a high-speed photo at the finish to determine the winner. A camera very much like the one that Muybridge deployed still determines the outcome of contested horse races.

3. Photo Finish Ubiquity

The idea of Muybridge’s photo finish was later expanded to include other sporting events, including foot races and swimming contests. Today, on TV and in film, the grace and agility of divers and swimmers, sprinters and footballers are presented in stop-motion, yet another of Muybridge’s contributions to the way we see and perceive.

4. Panorama

In January 1877, Muybridge placed his view camera on the roof of railroad magnate Mark Hopkins’ half-finished mansion in the posh Nob Hill neighborhood of San Francisco and began the process that recorded the most detailed and complete – though not the first – panoramic view of the city. Starting at 11am and using the contemporary equivalent of a telephoto lens, Muybridge took 13 photos as he carefully moved his camera around in 360 degree circle. The panorama remains the most complete description of the City’s “Golden Era” before its partial destruction in 1906 by an earthquake and subsequent fire.

5. The American West and US National Parks

Throughout the late 1860s Muybridge produced a stunning portfolio of the wild beauties of the American West, including breathtaking documentation of Yosemite before it became a national park. Multiple historians assert that the photos helped spur the National Parks movement itself. Theodore Roosevelt, the father of the US National Parks system, was directly influenced by Muybridge’s and other early photographers views of the American wilds.

On Saturday night at Glastonbury 2014, the mud, the terrible noodles and the hangovers will all be worth it. For the first time ever, a silent film will play the country’s leading rock festival. Neil Brand and the Dodge Brothers will perform their rousing score for William’s Wellman’s rail-riding rollercoaster Beggars of Life in the Pilton Palais cinema tent, at 6pm on 28 June. We’ll be there – will you?

“To the feminine mind nothing appeals quite as strongly as clothing, hats, or shoes – in fact finery of any kind,” opined Moving Picture World in 1916. Gentlemen spectators apparently preferred films with fighting in them. On finishing this fascinating survey of how the fashion and film industries met and grew together in the early 20th century, I’m inclined to excuse MPW’s sweeping generalisation.

Clothing, and fashion, are at the heart of everything that Hollywood has ever done. All film is spectacle, early film unambiguously so – and nothing epitomises the excesses of La-La Land more than the view of preening, primped movie stars lining up on the red carpet draped in borrowed couture and jewels. Baffling then, to remember that the first film actors were required to supply their own costumes. Turning up well-dressed to an studio (as the supremely stylish teenage Gloria Swanson did at Essanay) could secure you a chance at stardom. Even when studios had appointed a seamstress, numbers were so short that they would frequently be called upon to play roles on screen. In fact, Hollywood wardrobe departments would be staffed by many a former actress. And because few people kept proper records of who did what in the early studios, it is the memories of stars such as Swanson and Lillian Gish that often provide the clearest picture of how the costumes were supplied, chosen and recycled in-house.

To begin with, Michelle Tolini Finamore’s scholarly illustrated book examines fashion trends that made for great movie subject matter, from the exploited women working in sweatshops that churned out shirtwaists for America’s increasingly well-dressed urban working-class, to the extravagant picture hats that caused havoc in Nickelodeons, to the risque Paris styles that marked a lady out as a vamp. The idea that US fashions were practical and democratic and French ones outlandish and revealing kicks off a major theme in this book – the battle for fashion supremacy between first New York then LA with Paris.

Continue reading Hollywood Before Glamour: Fashion in American Silent Film – review

Don’t believe everything you read in the press. Contrary to published reports, legendary silent film actor Lillian Gish is not dead – she’s alive and well and totally winning at Twitter. Using the handle @MsLillianGish, the star of Broken Blossoms and The Birth of a Nation drops wisdom on the internet from a great height every day. Check out her Twitter biography, which is typically witty, informative and self-effacing: “I am the greatest actress of all time. If I had been a scientologist, you all would be one today. Yeah, I rocked it like that.”

Not content with enjoying Ms Gish’s wise words 140 characters at a time, I asked the star if she would be happy to answer a few questions for the benefit of the Silent London readers. To my great delight, she accepted. Unfortunately the time difference did not allow us to conduct the interview live, but I posted some questions to Ms Gish, and with her help of her loyal secretary she was able to answer them. Her responses are illuminating, I think you’ll agree. Here is the transcript of my interview with Lillian Gish …

This beautiful short, Hungerford: Symphony of a London Bridge, is a mini city symphony directed by Alex Barrett in 2010. It has won several awards, appeared at many festivals, and here at Silent London we have long admired it. Barrett, a writer, film-maker and regular Silent London contributor, has a more ambitious project in the works, though: London Symphony, a feature-length silent film about our fair capital. Barrett is a huge admirer of European silent cinema, and the city symphonies of the 1920s avant-garde. He plans to start shooting London Symphony later this year. Here’s how he describes the project:

London Symphony is a poetic journey through the city of London, exploring its vast diversity of culture and religion via its various modes of transportation. It is both a cultural snapshot and a creative record of London as it stands today. The point is not only to immortalise the city, but also to celebrate its community and diversity.

He’ll be asking for your help though – Barrett and his team want to crowdfund their movie, and you’ll be hearing more about that in the summer on these very pages.

For now, the best way to follow the progress of London Symphony is to sign up to the mailing list here . You can also follow London Symphony on Twitter @LondonSymphFilm and Facebook too.

It was a great honour for me to be asked to speak on the opening night of the Toronto silent film festival recently. It’s just a pity that geography was against us. But the speech was recorded ahead of time, and looked very smart, thanks to a colleague in the multimedia department at the Guardian generously helping me out – Andy Gallagher shot, produced, edited and did absolutely everything except sit on that blue chair.

You will probably be able to spot that it’s my first stab at presenting something like this, but it’s on the topic of silent film intertitles, which I am very enthusiastic about – the too-often unsung heroes of silent cinema. I hope you enjoy it.