This guest post is an edited version of an article on the origins of the early British thriller by Bryony Dixon, curator at the British Film Institute. The full article appears in the BFI’s new compendium on the thriller, Who Can you Trust?, now available in the BFI shop.

This guest post is an edited version of an article on the origins of the early British thriller by Bryony Dixon, curator at the British Film Institute. The full article appears in the BFI’s new compendium on the thriller, Who Can you Trust?, now available in the BFI shop.

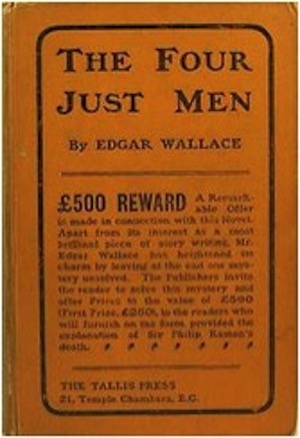

Next month’s Sunday Silent at the BFI Southbank is a rare chance to see a rare early film version of Edgar Wallace’s first great success, The Four Just Men. Released in 1921 by the Stoll Company, it was adapted by its director George Ridgewell, who worked on many of the Sherlock Holmes episodes for the same company. It’s a well-made film – nothing fancy but surprisingly competent for its year – from a well written novel, in fact a novel that is noticeably cinematic.

Try this passage from the opening of the original novel:

A NEWSPAPER STORY

On the fourteenth day of August, 19—, a tiny paragraph appeared at the foot of an unimportant page in London’s most sober journal to the effect that the secretary of state for foreign affairs had been much annoyed by the receipt of a number of threatening letters, and was prepared to pay a reward of fifty pounds to any person who would give such information as would lead to the apprehension and conviction of the person or persons, etc. The few people who read London’s most sober journal thought, in their ponderous Athænaeum Club way, that it was a remarkable thing that a Minister of State should be annoyed at anything; more remarkable that he should advertise his annoyance, and most remarkable of all that he could imagine for one minute that the offer of a reward would put a stop to the annoyance.

News editors of less sober but larger circulated newspapers, wearily scanning the dull columns of Old Sobriety, read the paragraph with a newly acquired interest.

“Hullo, what’s this?” asked Smiles of the Comet, and cut out the paragraph with huge shears, pasted it upon a sheet of copy-paper and headed it:

“Who is Sir Philip’s Correspondent?” As an afterthought—the Comet being in Opposition—he prefixed an introductory paragraph, humorously suggesting that the letters were from an intelligent electorate grown tired of the shilly-shallying methods of the Government.

The news editor of the Evening World – a white-haired gentleman of deliberate movement – read the paragraph twice, cut it out carefully, read it again and, placing it under a paper-weight, very soon forgot all about it.

The news editor of the Megaphone, which is a very bright newspaper indeed, cut the paragraph as he read it, rang a bell, called a reporter, all in a breath, so to speak, and issued a few terse instructions.

“Go down to Portland Place, try to see Sir Philip Ramon, secure the story of that paragraph—why he is threatened, what he is threatened with; get a copy of one of the letters if you can. If you cannot see Ramon, get hold of a secretary.”

And the obedient reporter went forth.

He returned in an hour in that state of mysterious agitation peculiar to the reporter who has got a “beat.” The news editor duly reported to the editor-in-chief, and that great man said, “That’s very good, that’s very good indeed” – which was praise of the highest order.

What was “very good indeed” about the reporter’s story may be gathered from the half-column that appeared in the Megaphone on the following day:

Cabinet Minister in Danger

Threats to Murder the Foreign Secretary

“The Four Just Men”

Plot to Arrest the Passage of the Aliens

Extradition Bill

EXTRAORDINARY REVELATIONS

It reads like a screenplay. The ramping up in stages of tension from the total under-reaction of the old codgers of the Athenaeum, to the more informed curiosity of the Comet, to the instant action of the Megaphone creates a mental image very reminiscent of the condensed montage-opening of the standard film thriller of the 1930s and 40s. To us the vision of whirling presses and scurry of the newspaper boys may be a cliché from the opening scenes of a thousand crime films, but it was a relatively new thing in 1921, when the story was first filmed, and certainly in 1905 when it was written.

For 1905 it was, when one of the best known British thriller novels was penned by a man who would come to be known as the ‘King of Thrillers’. Edgar Wallace was a Londoner of humble origins, who overcame a modest education to become a journalist and then an astonishingly prolific writer of ingenious thrillers, plays and film scripts. His lowbrow (his word) thrillers were written to be easily readable, were hugely popular and eminently adaptable for the screen. His works spawned some 200 films and television programmes, including famously at the end of his life, the first script for King Kong (1933). He died of a chill contracted while in Hollywood working on the film for Merian Cooper.

Continue reading The Four Just Men and the early British thriller →

This guest post is an edited version of an article on the origins of the early British thriller by Bryony Dixon, curator at the British Film Institute. The full article appears in the BFI’s new compendium on the thriller, Who Can you Trust?,

This guest post is an edited version of an article on the origins of the early British thriller by Bryony Dixon, curator at the British Film Institute. The full article appears in the BFI’s new compendium on the thriller, Who Can you Trust?,