This is a guest post for Silent London by the Lumière Sisters, a collective of writers who hang out over at the Chiseler.

Continue reading Better stars than there are in Heaven: the anarchy of early cinema

This is a guest post for Silent London by the Lumière Sisters, a collective of writers who hang out over at the Chiseler.

Continue reading Better stars than there are in Heaven: the anarchy of early cinema

I can’t believe I have been keeping this one to myself. As part of the process of writing a book on Pandora’s Box, I took a chance and wrote to a woman who I admire hugely, and who I know is a serious Louise Brooks aficionado. The novelist Ali Smith kindly agreed to answer a few hastily gathered questions on Brooks. Her answers were so eloquent, and inspirational, that I wanted to share them in full with you here …

It’s very common, since the 1960s, to talk about films belonging to directors. One hardly ever hears those auteurist labels on Brooks’s European films. I wondered if you felt these films mean something different when labelled as the work of their star rather than their director?

I kind of don’t care, and have never been much interested in labels. They’re always simplifications. But labels definitely preserve things over time, so thank god for that, and for the little flags they erect on the surface of knowledge so that people can see where to go to dig down deeper. I do despair, though, of the way our individual and common knowledge, both, get so lost so fast. Brooks, lost after the silent masterpiece years, till she died, was reclaimed in the 70s and 80s. I saw Pandora’s Box on TV in, I think, 1981. My mother, who wasn’t one for idle speculation or idle interests in things on TV, or idle anything, and who always went off to bed early, stayed up till 1am watching the film with me, till she couldn’t stay up any later, and in the morning the first thing she asked me was what happened at the end of that film?

Thirty years later, we have to do it all again – I heard your piece on Woman’s Hour, and sensed Jenni Murray’s astonishment at encountering Brooks for the first time. I was amazed – how could people not know Brooks? How could such a central cultural commentator not have her in her bones? (Unless she was simply being a kind introducer of Brooks to a listening audience who might bot know her.)* Where does that knowledge go? Here you are, doing that vital task.

Continue reading Ali Smith on Louise Brooks: ‘the revelation of movement’

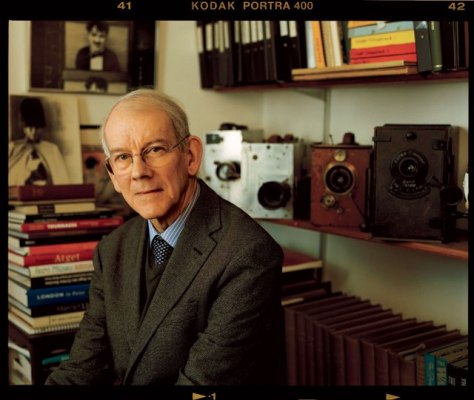

Ahead of the orchestral screening, cinema release and Blu-ray/DVD of Napoléon I am revisiting some old interviews I did at the time of the 2013 event at the Royal Festival Hall. Yesterday I published the edited transcript of my chat with Carl Davis about Roman orgies, perverting Beethoven and the pitfalls of watching Napoléon on a 1980s TV. Today, we have restorer Kevin Brownlow on his own epic Napoléon journey:

I was at home, and suffering from flu or something. I wasn’t at school. And this parcel arrived and I made a miraculous recovery. I got my parents in the front room and we ran it on the wall, and I had never seen cinema like this. This is what I thought the cinema ought to be, but it never was. I realised that what I had got was two reels of a six-reel version put out for home cinema use in the 20s. My mother said: “ That’s the most beautiful film you’ve got.” And so I started advertising in the Exchange and Mart until, I got the rest of it. And then people started coming to see it. I remember David Robinson was brought by Derek Hill, who was the assistant editor of Amateur Cine World, and he’s coming again 60 years later on the 30th [the 2013 screening]. He now runs the Pordenone Silent Film Festival [Robinson actually stepped down this year, and the new artistic director is Jay Weissberg].

Continue reading Kevin Brownlow on Napoléon: ‘What I thought the cinema ought to be, but never was’

There are silent movies and then there is Napoléon (1927). Abel Gance’s legendary biopic is ambitious in scope, style, technique, length and even breadth. And while there are competing scores and restorations, for us only the Napoléon recreated by Kevin and Brownlow and Carl Davis will do. You can see this version of Napoléon at the Royal Festival Hall this November, with the Philharmonia orchestra playing Davis’s monumental music, and in a cinema (probably) near you too. Plus, you will be able to take the film home too. This wonderful film is finally coming to DVD and Blu-ray this year – a release from the BFI, which promises to come laden with lots of tempting extras.

Ahead of the Napoléon-fest that awaits us, I wanted to share something rather special with you. Last time Napoléon played in London, I interviewed Brownlow and Davis for the Guardian. Necessarily, the conversation was truncated and edited for publication, but I still have the transcripts. So here, only a little tidied-up, is Davis and Brownlow on Napoléon, full-width.

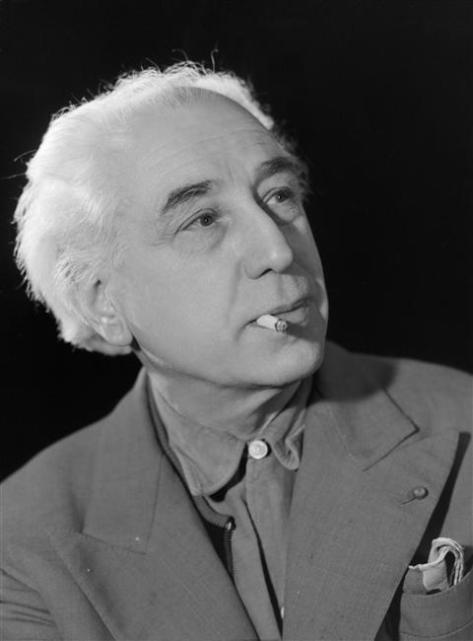

Today, I am publishing Carl Davis’s account of his Napoléon experience – come back tomorrow for Kevin Brownlow’s story.

The film flies by, when I am conducting. Conducting the score requires a lot of concentration, so you forget the time. It is very long but I’m getting better at it, because when this was proposed and we did it in 1980, no one was doing this, this was something that was dead by about 1929. It was all over, so there was no one to turn to say: “How do you do it? How do you organise yourself to do it? How do you create a score that’s going to run for five hours? What should its structure be?” I had to reinvent the process for myself and Napoléon was the first. Fortunately, a whole career and a whole library followed, so now I have a very defined technique for how to create the score, which I did not have in 1980. The difficulties stop when you know how to do it, and then I didn’t know how to do it at all. I just threw things together.

There is a prehistory to Napoléon and a very important collaboration with Kevin Brownlow before Napoléon: a Thames television series called Hollywood, which was based on a book of Kevin’s called The Parade’s Gone By. My relationship with him and the whole question of silent film started in the mid 1970s, around 1976. I then had the opportunity to meet survivors of the silent period. There still were people, y’know, very old then, but who were young at the time. The two really key people I met were still working. They were still playing for silent film but mostly on the big organ in LA and the most interesting person was a lovely little woman who lived in a house just behind the Hollywood sign. And I asked her: “How do you build up a long score for a film, for your own performances on the organ?” Her name was Ann Leaf and she was known as the last organist of the Paramount Theater in New York, the last cinema organist.

Anyway, she still did shows, you see, so she went to a big cupboard she had, which was full of music, and she would start pulling pieces out. She would say: “You know this is very good for chase sequences, and here’s this piece by Grieg, this is very scary music and this is a very, very nice piece to play for a love scene and this is Roman orgies.” I remember the Roman orgy moment! They felt that world music was absolutely at their disposal. You went very, very far. And the film companies established music publishers who would provide mood music, There’s a vast amount of rather anonymous pieces written specifically for different moods you see. And every cinema musician of that period would have a big library to draw on, depending on what kind of film it was.

So that conversation was really very, very critical. One could be very broad in one’s thinking. And then we came to Napoléon, Kevin and I and a man named David Gill. When we came to the end of the series and the series was broadcast in 1980 and was a very successful and well-thought-of and sold like mad around the world, I said very loudly at a celebration party: “Now that I’ve written about 300 clips, why don’t we try to do a whole film?” And then Kevin and David came up with Napoléon – probably the longest film ever made and that ever will be made, and that was never finished anyway. It keeps growing as more of it keeps being found. The original performance, which I think was just under five, is now five and a half hours, it’s grown by half an hour. And you have to revise the score, open out the score. Because it wasn’t as if, “Oh, we’ve found this one scene,” it was “Well we’ve found this little bit and that little bit.” And that shot and that whatever. So I’m in terror, you know, that as archives open, y’know, and as people find things in attics, forgotten drawers that suddenly …

Continue reading Carl Davis on Napoléon: ‘This is fun, this is extraordinary!’

This is a topic close to my heart, and hopefully yours too. After a successful campaign to produce the handsome Pioneers of African-American Cinema box set, Kino Lorber are back on Kickstarter with another project that makes film history a bigger, more inclusive, and more representative space. This time, Kino Lorber is coming for the women, with a set called Pioneers: First Women Filmmakers.

Has someone reminded you recently that more women worked in creative roles in the film industry during the silent era than do today? It’s a boggling fact, but it’s true. And keep repeating it, please. On the one hand, that titbit should spur today’s business into some serious equality action, now. On the other, it means we have a lot (I mean a LOT) of great but neglected work by female directors, screenwriters and producers to look over.

Continue reading Support the first women filmmakers on Kickstarter

The parade’s gone by for another year. The projector is empty, the Verdi is empty, even the Posta is empty. Yet again I can say watched a ridiculous number of films, but still missed many I wished I had seen. The Giornate was full to the brim with silent spectacles this year. And while it may be too early to speculate about Key Trends of the Weissberg Era, we can say the festival is in safe, and loving, hands. It was a vibrant schedule, crammed with exciting films. I had an especially good Giornate. How about you?

Today was always going to be bittersweet, but I offset that sharp tang of sadness with some great films and some enjoyably ludicrous ones, too. If we are going to remember this year as the year of big, beautiful movies (and I am at least), I enjoyed a fitting final day.

First question of the day: Who’s Guilty? Me, because I missed the final instalment in this diverting series, but I did arrive at Cinemazero in time for some Al Christie funnies. My eye was caught by a cross-dressing romp called Grandpa’s Girl (1924), but that wasn’t what I had stepped out for this morning.

I had a date with cinematic greatness, in the form of Ozu’s I was Born, But … (1932), the most sensitive and character-led of comedy dramas, shown in the Canon Revisited strand. Wonderful to see this projected, with Maud Nelissen’s ambitious and sensitive accompaniment. As a smart companion said: it’s a film about children but it’s really about all of us, at any age, at any time, in any place. This film is funny and wise and always beautiful: even when the camera is focused on the scruffy and mundane stuff of our scruffy and mundane lives, there is harmony and freshness. And oh, just make sure you never miss the chance to watch (and rewatch) this one. Promise? And the perky Momataro cartoon beforehand was a treat too.

Continue reading Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2016: Pordenone post No 8

And we deserved a little light sightseeing, after an emotional day, which began with a melodramatic double-bill. First, our customary voyage to the dark side of human nature in a Who’s Guilty? short featuring Anna Q as a jealous wife. Very little mystery in this one, but there was a novelty for the audience, as the Giornate’s two masterclass students took to the piano to share accompaniment duties. Jonathan Best and Meg Morley both did the drama proud, and we are very lucky to have both of these talented musicians playing in the UK.

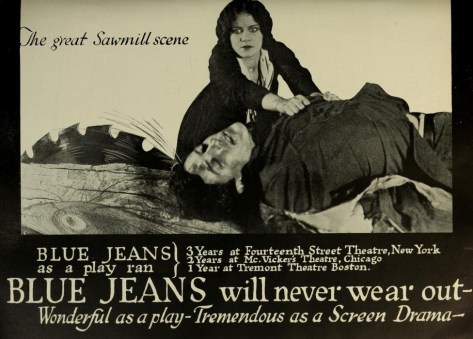

Then one of my most highly anticipated screenings of the festival: the well-known stage drama Blue Jeans (1917), rendered for the screen by John H Collins and starring the wondrous Viola Dana as a tomboyish orphan caught up in a complex small-town intrigue. There was a lot of plot and back story to pack into the 84-minute running time. It is really the kind of film where you might draw a diagram on your ticket stub in the café afterwards to make head or tail of the marriages and feuds etc. Disturbing to some of us also, that in the local elections, our hero stood for the Conservatives and the villain for the Liberals – but of course the baddie won that battle. Anyhoo, this one is well worth seeking out, if only for the famous climax at the saw mill when said hero narrowly escapes a haircut. Viola Dana to the rescue! And Donald Sosin’s music was just right, with a recording of Joanna Seaton singing a song inspired by the play adding another layer of nuanced dramatic Americana to the screening.

The rest of the morning was a delightful patchwork, the kind the Giornate excels in. A programme of French comic shorts directed by Emile Cohl, accompanied by Stephen Horne in suitably bonkers fashion on a plethora of instruments, included some wild animation, and surreal live-action comedy. Hugely inventive and almost impossible to describe in this space, but do take the chance to see these charming oddities when you can. Hopefully with Mr Horne and his bag of tricks.

The final slot of the morning was crowned with two curios from the William Cameron Menzies strand. An early sound film, The Wizard’s Apprentice (1930) was a trick-photographed forerunner to the more famous Walt Disney version with matchstick brooms sloshing tiny tin buckets. And the four reels remaining of The Dove (1927) were hot-blooded comedy drama, with the gorgeous duo of Norma Talmadge and Gilbert Roland offset by the leering machinations of Noah Beery as the self-aggrandising local Caballero. Before both of those, we met our friend Momotaro the peach boy from yesterday, this time on an underwater adventure to assassinate a shark. Brilliant fun.

The evening’s show promised great things. Erotikon? Erotic con more like. Yes, this Mauritz Stiller comedy could happily have been about 20% funnier, and no, there were not erotic thrills to be had on screen. Not by 2016 standards, at least. The main disappointment for me was realising that I had actually seen it years ago and what I thought was a me-premiere was in fact a retread. But it is a fine film, after all. A professor of entomology and his flirty wife seem to be headed for the skids because of her “infidelity”, but perhaps missus is not as bad as she has been painted? Maybe she is in love? Maybe the doddery professor has moved his fancy piece into their homestead under her nose and on false pretences? This Swedish sex comedy is lightly sparkled like the local prosecco and and was pleasingly open-ended. I was silently screaming at the end “C’MON, what is the real deal with that niece?” at the end. A grownup comedy, if not a totally hilarious one, and we were delighted to have John Sweeney’s witty accompaniment for this tale of crossed wires and mistaken glances.

Continue reading Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2016: Pordenone post No 7

Was this the perfect Pordenone day? Very likely. Sunshine, coffee and great films in abundance. Plus, not one but two appearances from Ivan Mosjoukine. Giornate excellence achieved.

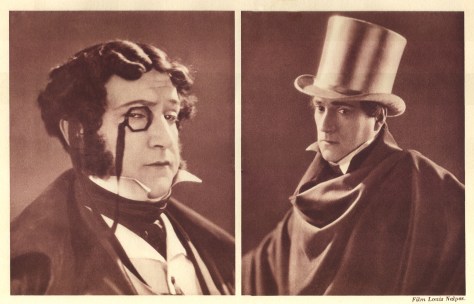

First things flipping first. Best. Who’s Guilty?. Ever. Anna and Tom are in love, a bit. Anna considers marriage but doesn’t come close. And the backdrop is a factory, which soon becomes embroiled in a workers’ dispute. Yes there is a strike! Much broader, bolder drama here, with nice location shooting and some sharply composed long shots. if Eisenstein had made potboilers. Maybe. And before the morning’s main event, a now-obligatory trip to an ersatz pre-revolutionary Russia with Ivan Mosjoukine in Der Adjutant des Zaren, a charming Japanese animation about a boy grown from a peach who became gentle and strong – but mostly badass enough to slay a shedload of ogres.

This morning also featured a quartet of City Symphonies to delight the eyes. I especially liked a very elegantly shot look at the reconstruction of Tokyo in 1929 (I know!), Fukko Teito Shinfoni and a zoom up Chicago’s main drag in Halsted Street (1934). A tour of Belgrade was pretty enough but lacked direction and so outstayed its welcome. I am very fond of these films though, and look forward to more. Continue reading Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2016: Pordenone post No 6

“It’s Christie Cristo day,” quoth a witty fellow Pordenaut today. And that was true – we were expecting more Al Christie comedies and Henri Fescourt’s lavish Monte-Cristo (1929) too. It also neatly encompasses the range of material one can expect from 14-odd hours in the Verdi. Slapstick comedy to prestige literary adaptations – plus today we had drama, poetry, newsreels, satire, political advertising and more … But it’s all that obscure niche they call silent cinema, right?

Continue reading Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2016: Pordenone post No 5

Did anyone ever tell you to beware of loose women in tight corsets? Tuesday at the Giornate was a tale of two Nanas: Jean Renoir’s acclaimed 1926 adaptation of the Emile Zola novel played in the afternoon, but in the morning we saw a recently rediscovered Italian version, starring noted diva Tilde Kassay. The Verdi audience are accustomed to beautiful temptresses by this point, so we were well judged to decided who wore it best…

First, here’s what I didn’t see. One British-Soviet curio, Three Live Ghosts, which I saw last year in Leicester and wrote about here. I also ducked out of The Guns of Loos, having seen it on the same occasion, and then a few weeks back at the BFI too. I wimped out of the morning’s western marathon too, after a couple of films. Early westerns don’t always thrill me, but in this case I had some work to do instead. And it seems that I missed out on a very impressive rattlesnake. Ah well, snakes and ladders. I have a less impressive reason for missing the last film of the day, but I stand by it: good wine, good company, great gossip.

However, nothing can tear me away from my Who’s Guilty? morning treats, which have me more hooked than any soap opera. Yet again Anna Q Nilsson got married in haste (to the always-appealing, imp-faced Tom Moore, the son of the newspaper editor investigating her senator father’s corrupt affairs) and repented in haste too, as a lawsuit for abduction revealed a harsh truth about her childhood that led her straight to the brink. The brink of the lake that is. Thanks A Trial of Souls (1916) for that early morning anguish. Continue reading Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2016: Pordenone post No 4

However, nothing can tear me away from my Who’s Guilty? morning treats, which have me more hooked than any soap opera. Yet again Anna Q Nilsson got married in haste (to the always-appealing, imp-faced Tom Moore, the son of the newspaper editor investigating her senator father’s corrupt affairs) and repented in haste too, as a lawsuit for abduction revealed a harsh truth about her childhood that led her straight to the brink. The brink of the lake that is. Thanks A Trial of Souls (1916) for that early morning anguish. Continue reading Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2016: Pordenone post No 4

On a blissfully sunny Monday in the town we’d really rather you didn’t call “Porders” we saw films which taught us that money makes the world go round, and films that transported us to the far side of the globe. Come take a trip …

The Who’s Guilty? strand continues to entertain – we’re all hooked. Although I was worried that Anna Q Nilsson kept getting married and kept suffering as a result and would never learn. A case in point was today’s first film, the second reel of Sowing the Wind (1916). However, things took a turn for the modern in Beyond Recall (1916) as an extravagantly costumed Anna Q took a job (really!) in the District Attorney’s office and did her very best to save the life of Tom Moore, wrongly accused on circumstantial evidence of murdering his girlfriend. The DA ignored her arguments, so unfortunate Moore was sent to the chair, grimly illustrating some still-relevant troubles with sexism in the workplace and the fate of poor people in the justice system. Anna Q can’t catch a break.

Ever fallen in love with a film you shouldn’t have fallen in love with? I did, tonight, I must confess. I am utterly besotted with a Polish silent that isn’t a silent at all, really, but a musical of sorts that has long since parted company with its Vitaphone discs. What remains of Janko the Musician (Janko Muzykant, 1930) is a very poignant film, with easy charm and visual lyricism.

Young Janko is a peasant boy in rural Poland, and although he is a gifted musician, he hasn’t the funds to develop his talent, or even practise it. His homemade rustic violin is ingenious, but far from sufficient. In fact, for a young man of his class, artistic endeavour is so far off-limits that he is criminalised for his love of music, which destroys his poor mother and nearly breaks him. Even when it seems that he has used his talent to transcend these social divides, his past catches up with him.

Janko is played by two strikingly handsome actors, Stefan Rogulski and Witold Conti, and the supporting cast, notably his two partners in demi-crime in the second half of the film are excellent. Without the sound discs, it is still very easy to follow the film, as the dialogue was always intended to be carried by the intertitles, but we are left with longish sequences when Janko plays, or others sing. To fill these silences, we had a very sympathetic live (improvised?) score from Günter Buchwald, Frank Bockius and Romano Tadesco, which left the Verdi every bit as spellbound as the crowds who gathered to hear Janko play. The first third of the film is especially successful, and the first two-thirds very good indeed. If it felt slower in that last third it is because we have left Janko’s natural habitat and his essential conflicts behind. This film is at its best in the countryside, and wherever people gather, not in high-class drawing rooms and court offices. It was also 35 minutes longer that advertised, so I guess it was actually slow, but I didn’t hear anyone complaining about that. Continue reading Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2016: Pordenone post No 2

You don’t have to be a Giornate regular to know that everything old is new again … but it helps. So, as the Pordenone Silent Film Festival celebrates its 35th birthday, we welcome a new era, with Jay Weissberg taking over as director. A change of course or more of the same? There is only one way to find out …

Greta Garbo is immortal, and an opening night gala featuring a lush Carl Davis score for a classic Hollywood silent feels like a timeless choice also. Tonight’s screening of the shamelessly romantic The Mysterious Lady (1928) ticked all the boxes for a wandering Cinemutophile yearning for a home from home in northern Italy. It is a beautiful film, just the right side of presposterous, with Greta Garbo as a Russian super-spy seducing Austrian officer Conrad Nagel and falling in love in the process. How inconvenient, especially for her lecherous boss, Boris, played by Gustav von Seyffertitz. The score, conducted by the maestro himself, was a Hollywood number through and through – thrilling to the too-perfect romance between the leads and unabashedly ramping up the intrigue. Touching too, that one of my all-time favourite silent films, A Propos de Nice (1930), played before the main feature in a gesture of sympathy and solidarity with the the people of the French Riviera, who suffered a terrible attack earlier in the year. It looked sublime on the Verdi screen, needless to say, and especially so with John Sweeney’s sparkling accompaniment

Continue reading Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2016: Pordenone post No 1

The concept of “Early Murnau” is a little bittersweet. The German director had such a short career that the films in this new collection from Masters of Cinema take us up to just six years before he died. And while his most famous film was made during the period (1921-25) covered by this box set, that work, Nosferatu, is not included. The set ends just one year before his hypnotic Faust was made, and two before his Hollywood masterpiece Sunrise.

This is technically middle Murnau, then, or “the Murnau you may have missed if you only knew Nosferatu and the surviving Hollywood work”. All the same, this is a gorgeous collection of distinctive, spectacular films, well worth adding to your shelf. All of the films in the set have been made available on DVD from Masters of Cinema previously, but here together, on Blu-ray, they represent a far better bargain.

The journey through Murnau’s lesser-sung German work begins in 1921 with Schloss Vogelöd, a country-house mystery rendered mysterious and dreamlike at the director’s touch, and climaxes with the bracing and inventive Molière adaptation Tartuffe (1925), which introduces an especially noxious virtue-signalling hypocrite and hangs him out to dry. In between we delve into the romantic and financial misery of a poetically minded clerk in Phantom (1922), and the related entanglements of an aristocrat in Die Finanzen de Grossherzogs (1924). Indisputably, the highlight of the collection is the low-key masterpiece Die Letzte Mann (1924) starring Emil Jannings as the hotel doorman whose life hits a downward spiral when he is demoted to a toilet attendant.

As the many extra features and essays included with the set attest, Murnau’s oeuvre is hugely varied, swinging from genre to genre and rarely settling in one place for long. Stylistically, though, he is mistakably himself at all times. You can see the walls of the city bend down to oppress the heroes of both Phantom and Die Letzte Mann, for example. And you may already have noticed that the films above share a set of preoccupations with money and social position, with impossible aspirations and with toxic pride.

Continue reading Early Murnau review: a set for the silent cinephile to linger over

The silent movie revival (© 2011) takes many, many different forms. A few months back, in February, I noticed a clip from a silent movie popping up in my Facebook feed a lot. Not a long clip, just a short one – a single tracking shot from a well-known movie. The Facebook page that shared this video so successfully had rendered the name of the film in English and French – “Wings (Les Ailes, 1927) an avant-garde film.” A colleague of mine, one of the brainiest in the building, sent me the link, telling me that he had seen a clip from a really special silent film and he thought I would like it. He was a bit miffed, somehow, when I told him that it was a Hollywood movie, a Top Gun style film, which won the first ever Best Picture Oscar.

That was a bit harsh of me, I shouldn’t have been so blunt and I think I rained on his parade a little. Lots of people don’t think they like Hollywood films, especially the kind that win Oscars. Although lots more do, surely. And French avant-garde films are much cooler than Top Gun – I probably agree with that. I did wonder how many people thought that they were sharing an obscure example of le septième art rather than slick Hollywood film-making, when they pushed that nightclub tracking shot around Facebook.

Today, I saw the clip was back – transformed into a very smooth gif by the twitter account @silentmoviegifs and going great guns for shares and likes. This time it was more accurately credited. Wow, People really love Wings! Or at least this part of it.

This animated 2015 piece about the cinematography in Wings puts the tracking shot above the flying sequences, and this may be where the gif first took off. My clever colleague had read on Facebook that the smooth camera movement was achieved by splitting the tables in half as the camera moved forward. Now that is quite bizarre, although this shot was quite tricky to achieve. This YouTube video explains how it really worked:

What if all your silent cinema dreams came true? What if they found those missing reels of Greed, or a pristine print of 4 Devils, and you had to admit you were disappointed? Say it isn’t so. But consider this: if 80% of silent films are lost, does that mean that silent cinephiles, by definition, are hooked on the chase, the thrill of forbidden fruit? There are so many films we will never get to see, and others that we see only rarely or in incomplete versions – perhaps we’re all addicted to the legend.

It’s worth thinking about at least, and it was at the forefront of my mind as I sat down early this morning to watch a preview of the digital restoration of Abel Gance’s Napoléon. Yes, that Napoléon, the version heroically pieced together by Kevin Brownlow and magnificently scored by Carl Davis. I have been lucky enough to see it once before, at the Royal Festival Hall in 2013 – before that, I was too skint to stump up for a ticket. It was amazing, and I will never forget the frisson I felt as the film began and I thought: “Finally, finally I am going to watch this thing!”

However, if sitting down to watch Napoléon were just as simple as sitting down to watch Coronation Street – no dinner reservation, no train to London, no babysitter, no £40 ticket – would the thrill be the same? As I took my seat in NFT1 I began to worry that the sheen of Napoléon would have faded, but the truth is no, it has just shifted a little.

Continue reading Napoléon for all: Abel Gance’s epic film goes digital

While the rest of us spent the summer wincing at the news and Instagramming our hot dog legs, Neil Brand has been in a better place. In a Hollywood vision of Sherwood Forest, to be specific, cooking up a new score for Allan Dwan’s 1922 blockbuster Robin Hood, starring the wonderful Douglas Fairbanks. The score will be performed by the BBC Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Timothy Brock, at a special screening of the movie in the Barbican Hall on 14 October.

You can book your tickets here. And you can read a little more about the movie here. But what I am dying to tell you, and you can call me Boasty McBoastFace if you like, is that I have had a sneak preview of the score. Yes I have. Wanna know what it’s like?

Continue reading Neil Brand’s Robin Hood score: a sneak preview

Have you cleared your calendar for October yet? Between Pordenone, for those lucky enough to go, the Robin Hood screening at the Barbican, and the Kennington Bioscope comedy festival, not to mention the mounting excitement about Napoléon in November, it’s a busy month to begin with. And then the London Film Festival pops up in the middle of October with its own programme of silent screenings.

So we already know that the Archive Gala will be the Irish-set thriller The Informer. And we already know that it is on the same day as Robin Hood. So that’s your first now-traditional schedule clash.* It’s also something of a shame that the Archive Gala will be at BFi Southbank, not the festival’s specially built 780-seat pop-up cinema in Victoria Embankment Gardens, where all the other galas will be held, although I assume that is to do with finding space for the band. Designers of these new-fangled cinemas always forget the orchestra pit.

However, here’s what the rest of the 60th London Film Festival has got planned for you, silents-wise. Erm, not quite as much as I would have hoped …

Continue reading London Film Festival 2016: the silent preview

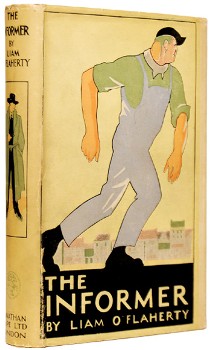

One of the most exciting annual announcements in the silent film calendar, at least for us Brits, is the London Film Festival Archive Gala. So start rolling those drums now. This year, the beneficiary of a digital restoration, a new score, a gala screening and and a Blu/DVD release is … Arthur Robison’s The Informer (1929).

This rare silent adaptation of Liam O’Flaherty’s famous novel is set among Dublin revolutionaries in the early days of the newly independent Irish Free State, formed in 1922. The Archive Gala will take place at BFI Southbank on Friday 14th October, 6.30pm in NFT1 and features a specially commissioned live score by Irish composer Garth Knox with a six piece ensemble.

The silent Informer is a British-made movie, filmed at Elstree by British International Pictures, but has the flavour of an international co-production too, starring Englishman Carl Harbord, Swedish Lars Hanson, and Hungarian Lya de Putti (you may know her from Varieté). The story is set in early 1920s Dublin, during the first years of the Irish Free State and it is a tale of revolution and betrayal, with an underground cell of activists torn apart when one of their member accidentally kills a police officer.

According to novelist O’Flaherty, he wrote The Informer “based on the technique of the cinema,” as “a kind of high-brow detective story”. The BFI says that the film draws on this lead, with an expressionist vibe that looks forward to film noir. Robison’s studio-shot film is tense, and claustrophobic, reflecting the anxieties of the lead characters, almost exclusively shot in mid-shot or close-up.

The dense narrative develops in a short time heightening the intensity of emotional effect. Our sympathies are challenged to deal with the complexity of personal versus political loyalties, where no-one is entirely innocent and the implications of seemingly minor or impulsive decisions create inescapable moral dilemmas for all the protagonists.

The new score for the gala and Blu-ray release has been written by a composer from Ireland, Garth Knox. The music draws on his interest in medieval, baroque and traditional Celtic music, and uses some traditional Irish instruments as well as avant-garde composition styles. It will be performed by a six-piece ensemble including accordion, flute, Irish pipes and viola d’amore.

The Informer (1929)

The digital restoration has substantially cleaned up the film, which was made in both silent and talkie versions at the dawn of the sound era – and reintroduced the lavender tinting it would have enjoyed on its first release.

More to come on this for sure … Silent London will keep you informed.

The consensus view on Clyde Bruckman was summed up by Tom Dardis, biographer of Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton: “he was not very funny, and he drank too much”. Matthew Dessem’s The Gag Man, an entertaining and revelatory study of the writer-director, does little to erase that image, but does examine how he came to “direct” some of silent cinema’s greatest comedies, and tells one heck of a Hollywood yarn.

Bruckman was a journalist who entered the film industry as an intertitle writer, before becoming a “gagster”. The “gag men” would conceive visual jokes for silent comedies, working in groups, throwing ideas around, so it’s tricky to say who did what. However, Bruckman is credited with the brilliant concept for Buster Keaton’s The Playhouse (1921). The star had a broken ankle, which limited his usual acrobatic display. Bruckman sketched out an idea for creating laughs out of camera trickery instead of physical exertion. Thanks to deadly timing on behalf of cameraman and star, the multiple exposures work perfectly, including a triumphant sequence in which nine Keatons dance together.

Continue reading The Gag Man review: a brutal insight into the silent comedy business