Fresh from a theatrical release and a flurry of Halloween shows, Nosferatu springs into life on Blu-Ray, courtesy of Eureka’s Masters of Cinema label. This new release is an update of the label’s previous DVD, but features the Symphony of Horror in gleaming 1080p glory, with a handful of new features as a bonus prize.

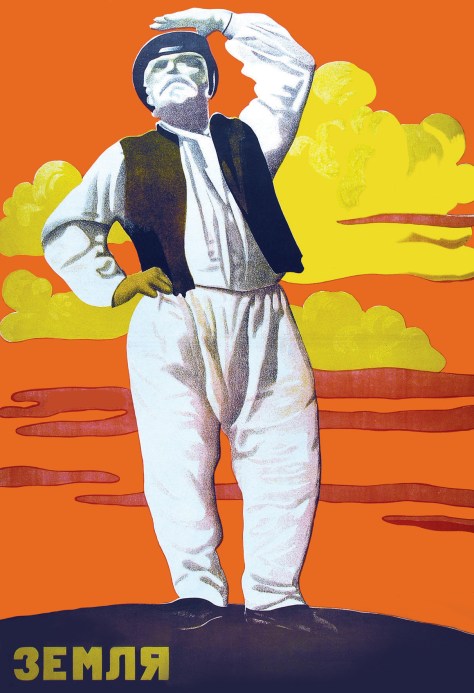

This is a precious object then, a totemic silent film in beautiful packaging and supported by more supporting material in the form of articles, audio commentaries, interviews and documentary footage than you could possibly expect. Apparently, there has been more work done to improve on the 2007 restoration – if you’ve seen this in the cinema already you know how pristine the prince of darkness looks here. And that is so important. Nosferatu is far more than shadows. Arguably, rewatching Nosferatu on Blu-Ray at home, rather than at an amped-up and spooky live show, you enjoy its gorgeousness rather than the horror thrills: those painterly landscapes in their pastel tints. There’s nothing like the black-white-red-purple palette of modern gothic horror here – which keeps the film fresh but always uncanny. The music helps, too. The score from Nosferatu’s first run plays up the prettiness and romance – until it can’t hold out any longer.

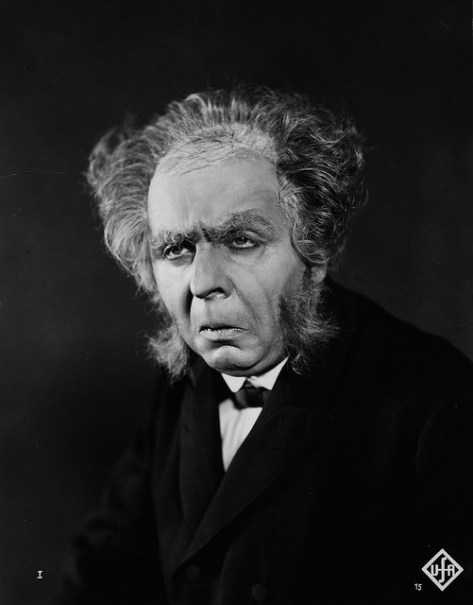

Do we need to recap? I’ll do this at high speed, like Orlok’s spectral carriage dashing through an ethereal white forest. Nosferatu is an adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, in all but name, with the action transferred to Germany. Max Shreck is the snuggle-toothed vampire Orlok, the young and preternaturally talented FW Murnau sits in the director’s chair. The movie was produced and designed by Albin Grau, an artist with a keen interest in the occult. And it’s brilliant: both beautiful and terrifying. A horrific spooky story, with eerie contemporary import. Remember that Europe has just come out the other side of a world war and a brutal flu epidemic, then look again at the devastation wreaked by Orlok here.

In fact, even if you’ve never seen a second of Nosferatu, you’ll know its most famous shot: Orlok’s hunched shadow stretching up the wall as he climbs the stairs. That shot has became a visual shorthand for horror, for imminent danger. It’s remarkable, by contrast with all the films that have appropriated the stair shot, that Murnau’s Nosferatu avoids any such shortcuts: turning leafy landscapes into places of horror, playing violence as romance, and romance as violence. Nonagenarian special effects such as Orlok packing himself into his coffin, and later lurching out of it, still feel vibrant. Perhaps that’s partly because this is a relatively decorous scary movie, with just a few drops of blood standing in for Orlok’s grotesque appetite. Murnau drenches Orlok’s victims in creeping shadows, rather than cascading gore. You’ll jump like a child at the sight of a rat, believe me.

But even if you remember those shocks from a long-ago screening, I would urge you to acquaint yourself much more closely with this poetic, audacious film. There’s far more here than a textbook paragraph on Expressionism can brief you on. Each repeat viewing brings something new to the fore, and that’s where the MoC treatment excels. Let me see, this disc contains two audio commentaries (one by R Dixon Smith and Brad Stevens from 2007, and another by David Kalat, who is so charming and impressively knowledgable that we’ll let him off for describing Stoker as an Englishman), two interviews (an previously seen chat with Abel Ferrara, and a new one with BFI Film Classic author Kevin Jackson). There’s a German language doc, which includes lots of location footage, and a booklet of articles and gorgeous images. The new commentary and interview are particularly sharp on unpacking myths around Nosferatu, from the etymological origin of the name to Grau’s spiritualist beliefs.

Take it from me, you need more Nosferatu in your life.

Take it from me, you need more Nosferatu in your life.

Nosferatu is released by Masters of Cinema on DVD and Blu-Ray in the UK on 18 November 2013. Order the Blu-Ray from Movie Mail.