https://instagram.com/p/4M177yOZ_W/

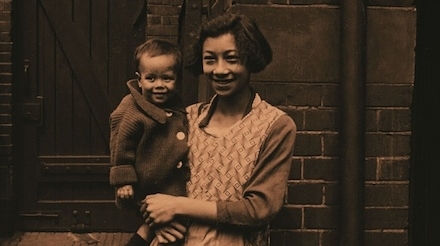

At this time of year, a silent film fan starts packing sun cream and sandals and contemplating a journey south to enjoy some warm weather and classic cinema in the company of like-minded souls. But there will be plenty of time to talk about Bologna later. This weekend just gone, I set forth in a southerly direction on the Bakerloo line, snaking under the Thames to the Cinema Museum in Kennington, south London. What I found there was very special indeed – and long may it continue. Everyone who was there with me will relish the idea of the Kennington Bioscope Silent Film Weekend becoming a regular thing, and for the lucky among us, an amuse-gueule for Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna.

We love the Kennington Bioscope, that’s already on the record, so the Silent Film Weekend is a lot more of a good thing. The team behind the Wednesday night screenings, with the help of Kevin Brownlow and a few guest musicians, have translated their evening shows into a two-day event. And with the added bonus of delicious vegetarian food courtesy of the café at the Buddhist Centre next door. It was a triumph all round.

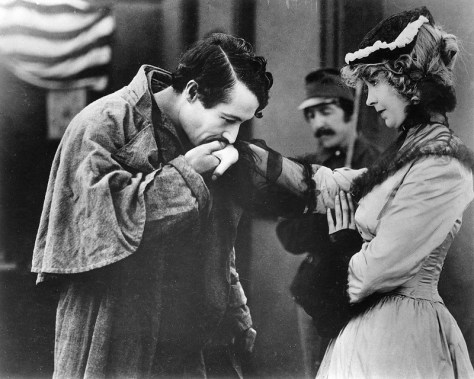

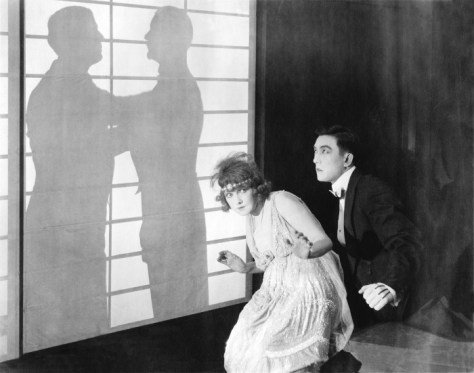

The programme for the weekend, which you can read here, packed in quite a few classics along less well-known films. I was more than happy to reacquaint myself with Ménilmontant (1926) and The Cheat (1915) – especially on high-quality prints projected by the genius Dave Locke and introduced by knowledgeable types including the afore-mentioned Mr Brownlow. What a joy also, to see the BFI’s Bryony Dixon proudly introduce a double-bill of H Manning Haynes’s WW Jacobs adaptations: The Boatswain’s Mate (1924) is surely destined for a wider audience. And if you haven’t seen Colleen Moore channel Betty Balfour in Twinkletoes (1926) you really are missing out.

But for this report I have decided to focus on the films that were new to me. I appreciate that’s an arbitrary distinction for other people, but this way I can fold in the element of … SURPRISE.

Continue reading Five films I saw at the 1st Kennington Bioscope Silent Film Weekend