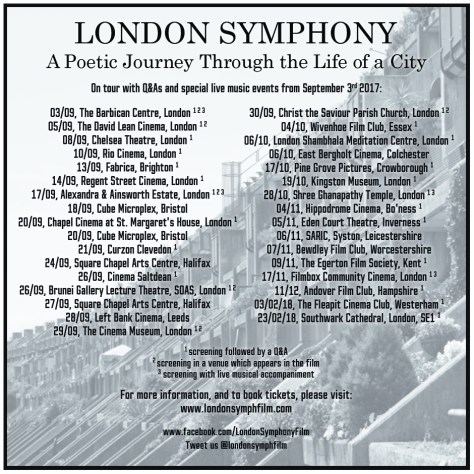

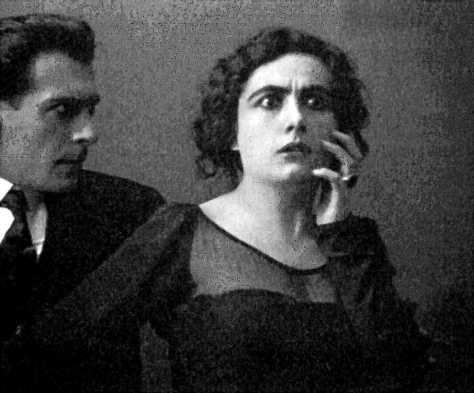

“Why are your thoughts in America when you tell me your heart is in Italy?” Well, Theda Bara, since you ask, it’s because the Giornate showed a mid-period silent American classic on Friday night. A Fool There Was (1915), or as I prefer to call it, The Cabinet of Dr Libido, is a bizarre film, by turns prosaic and ethereal. The plot is slight, but the imagery is immense, with Bara as an especially vampirish vamp, her long dark hair framing a milk-white face in the most demonic way. She can bat away a revolver with a rose and drive a man to distraction with a glimpse of ankle or shoulder – these are superpowers, not seduction techniques. No wonder the image of Fox’s foxy lady endures even when so many of her films are lost, burned up in the heat of her own fiery screen presence. And as silents go, A Fool There Was has great words, not least in the recurring appearance of Kipling’s ‘The Vampire’, but in a few killer lines of dialogue, one of you which you already know is going to appear below. And speaking to the film as well as for it, tonight, we had a brilliant new score written by Philip Carli and played by a quintet, which kept pace with the film’s many twists and dramatic moments and also added some much-needed nuance, as in the heartbreaking scene in New York traffic when Schuyler ignores his own daughter’s pleas, so engrossed is he in his new paramour’s charms.

After Theda Bara, Hollywood turned to Pola Negri for a more authentically exotic vamp, although a more romantic one too. So it was fitting that one of her early German films, Mania (1918) closed the evening’s viewing. I’ve written about that one before, a couple of times, so I skipped it tonight.

But it was a great day for strong leading women, from a selection of cheeky Nasty Women shorts (I loved Lea causing havoc in an office full of besotted men) and beyond. We had the rich, psychological drama Thora Van Dekan (John W Brunius, 1920), for example – a story of a woman trying to protect her daughter’s inheritance from her wayward ex-husband, in the face of opposition and judgment in her village. Pauline Brunius is hypnotic in the lead role as a spiky, often unlikeable, singleminded and clearly emotionally brutalised woman trying to do her best by her child. This was a sombre piece, all the more so with Maud Nelissen’s downbeat improvisation, and just the sort of thing that nestles into your brain cavities and makes itself at home for days.

Continue reading Le Giornate del Cinema Muto 2017: Pordenone post No 7